Platforms at the gate? Initial reactions to the Commission’s digital consultations

On 2 June 2020, the European Commission launched a consultation on proposals for a new competition tool (NCT) and the Digital Services Act (DSA) package. If enacted, they would represent a significant change in competition enforcement in the EU, and a major step-up in the regulatory rules and oversight of the digital economy. In this article, we set out some initial thoughts on the proposals from an economic perspective and discuss some relevant considerations for consistent, proportionate and effective policies that may lead to better consumer outcomes.

Introduction

The recent Commission impact assessment publications cover three distinct regulatory initiatives. One proposes an ex ante regulatory framework for ‘large online platforms benefitting from significant network effects and acting as gatekeepers’ (henceforth, ‘ex ante platform regulation’),1 while the second contains modifications to the liability rules around content, goods and services available from online platforms.2 Together, these two impact assessments cover the main options for reform that are being considered under the DSA package announced in February 2020.

The third is an impact assessment on options for a NCT to complement the traditional tools of Articles 101 and 102 TFEU that the Commission can use to address competition concerns. While the first two initiatives specifically target digital markets, the NCT is potentially a broader tool that would apply to all sectors.3

We focus on two specific questions raised by the ex ante platform regulation and the NCT initiative.

- First, whether there is currently an ‘enforcement gap’ that requires granting authorities new tools, and, if so, what is the appropriate threshold for intervention in digital markets?

- Second, as regards the relationship and possible tension between the goals of competition (economic efficiency) and ‘fairness’—an explicit goal of the ex ante regulation—what are the implications for the analysis and design of both initiatives?

It is clear that whichever options contained in these consultations are implemented (assuming at least one is implemented), there will be a major step-up in enforcement action, both ex ante and ex post, in the digital sector.

We have two main observations on how this enhanced enforcement action can be given the best possible chance of achieving its intended aims (i.e. ensuring a fair trading environment and increasing the innovation potential in the EU digital single market).

- First, the principles and evidentiary standards of competition law should remain at the heart of any ex ante or ex post framework. In practice, this would mean rejecting regulatory options involving per se prohibitions (e.g. blacklisting certain practices) absent unambiguous evidence that a practice is proven to be harmful and favouring a case-by-case analysis of platform business models, their incentives and, ultimately, the effects on consumers. This would also mean seeking to align the rationale for intervention (both in the NCT and ex ante regulation) with well-understood concepts such as dominance and robust evidence of actual or likely effects on competition and consumers.

- Second, to the extent that fairness goals are pursued through one or more of these tools, the primary focus should be on fairness of process (as in the existing P2B Regulation) as opposed to fairness of outcomes. If fairness of outcomes is pursued, this must also take account of the efficiencies and the value created by platforms’ business models and practices, for consumers and other platform users.

What are the Commission’s proposals?

New competition tool

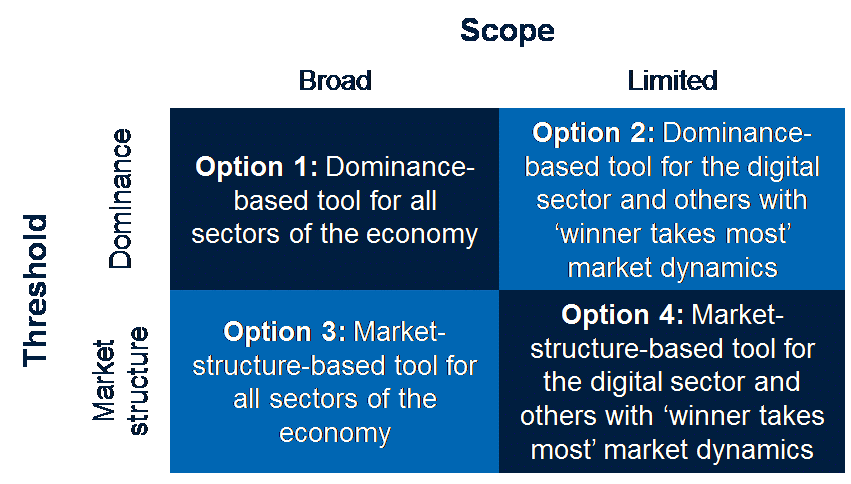

The NCT initiative is motivated by the possibility of structural risk or lack of competition which cannot be easily resolved through Articles 101 or 102 TFEU.4 The Commission presents four options for the potential NCT, which vary according to the threshold and scope. The threshold for using the NCT, discussed further below, might be based on: dominance or structural features of markets; whereas the scope might be ‘limited’ (focused on digital or digitally enabled markets) or ‘broad’ (across the economy as a whole).

Figure 1 The four options under the proposal for an NCT

Ex ante platform regulation

In parallel, the Commission is consulting on options to introduce an ex ante regulatory framework for large platforms with ‘significant network effects acting as gatekeepers’. This initiative arises from a range of concerns which, according to the Commission, may lead to risks of reduced social gains from innovation and large-scale unfair trading practices.5

Three options are discussed for ex ante platform regulation.

- Revising the P2B Regulation, by extending its scope to include prescriptive rules on certain practices (such as certain forms of self-preferencing, data access policies and unfair contract terms). Importantly, this option would have a broad ‘horizontal’ scope and would not be targeted only at large platforms considered to be gatekeepers.

- Collection of data from large platforms by a dedicated regulatory body, the goal being to gain further insights into the business practices of these platforms. This option would not include any power to impose remedies.

- Adopting a new ex ante regulatory framework for gatekeepers, where gatekeepers would be identified by a yet-to-be-agreed set of criteria.6 Two sub-options are discussed as to how such a framework could be structured:

- a. blacklisting certain practices by gatekeepers, and setting out clear obligations (e.g. blacklisting self-preferencing);7

- b. tailor-made remedies for specific gatekeepers on a case-by-case basis. These remedies could include blacklisting practices as above, as well as others such as (non-personal) data access obligations, personal data portability or interoperability requirements.

The perceived enforcement gap and the appropriate threshold for intervention

As can be seen, both consultations aim to tackle very similar concerns in digital markets, as also articulated in a wide range of reports (most notably, the Special Advisers Report, the Furman Review and the Stigler Centre Report). In fact, these reports also argued that the existing toolbox of competition authorities and regulators is not sufficient to deal with these concerns effectively, and that changes and additions to the toolbox are necessary. In other words, the case for reform is predicated on the existence of an enforcement gap.

Mind the gap

It is therefore worth probing the nature of this alleged gap in more detail. There are at least two aspects that are relevant here.

- Timing of harm: has the harm to consumers materialised, or is it hypothesised to happen in the future if there is no intervention?

- Cause of harm: is the harm arising or likely to arise because of the unilateral actions of dominant firms, or because of structural market failures (including unilateral practices by one or more non-dominant firms)?

Given that Article 102 TFEU typically seeks to address (alleged) harm arising from historical/ongoing conduct of dominant firms, three potential ‘gaps’ could be conceived.

- Gap #1: harm that is hypothesised to happen in the future because of the risk of future practices by dominant firms.

- Gap #2: harm that is hypothesised to happen in the future because of existing structural market failures.

- Gap #3: harm that is already happening because of structural market failures.

There is also a debate about whether the existing toolkit is sufficiently agile to allow the Commission to act quickly enough, providing an additional motivation for introducing new tools.

There are good legal and economic reasons why Article 102 primarily focuses on actual or potential harm caused by specific ongoing practices by dominant firms. Firms in a dominant position can behave independently of consumers and competitors and can therefore dictate the parameters of competition. At the same time, competition law recognises that acquiring a dominant position can be the result of significant investments and innovative behaviour, as well as a reflection of the efficiencies, and value created and shared with business partners and consumers. Therefore, being dominant by itself does not result in presumptions of guilt or wrong-doing.

The European SMP framework for electronic communications (telecoms) networks

There are examples where a position of dominance has been a cause for concern due to the risk of harmful practices. This has led to the creation of ex ante regulatory frameworks to deal with problems before they give rise to harm.

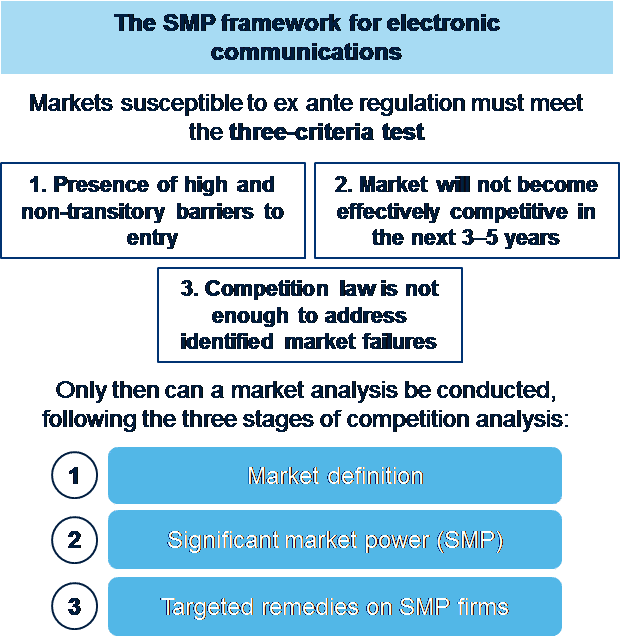

The most prominent example in this regard is the ex ante regulatory framework for the electronic communications sector in Europe, which has been referred to by the Commission as a source of inspiration for regulation in digital markets. This framework, which has been in place since 2002, is based on identifying whether one or more operators hold significant market power (SMP)—a position equivalent to dominance under competition law. If such a finding is made, the regulator is given powers to impose remedies. The remedies are chosen from a specific list, aimed at addressing the most common problems that may arise in the telecoms sector, such as excessive retail or wholesale prices, or refusal to provide access to third parties.

As can be seen, the SMP framework in electronic communications addresses gap #1 identified above.8

Among the Commission’s initiatives, the options that share the greatest similarities with the SMP framework are Options 1 and 2 of the NCT. Under these options, the Commission would be able to impose behavioural and, where appropriate, structural remedies on dominant companies before any harmful practice has taken place, as in the SMP telecoms framework.

However, despite these similarities, Options 1 and 2 are being proposed by the Commission as new competition tools, rather than as ex ante regulatory instruments. This is surprising because the SMP framework in electronic communications is explicitly not considered to be a part of the EU competition law toolkit. Indeed, electronic communications markets can be regulated only if they pass the three-criteria test for markets susceptible to ex ante regulation and, in particular, the third criterion: that competition law alone is insufficient to address the market failure(s) identified. See the figure below.

Figure 2 The ex ante SMP framework for electronic communications in Europe

While there are a number of important differences in the economics of the telecoms and digital sectors, the success and longevity of the ex ante SMP regime owes a great deal to its close alignment with the legal principles and economic analysis required under competition law. This is an important lesson for the design of new regulatory tools for the digital economy.

Platforms at the gate?

The similarity of Option 2 of the NCT consultation to the ex ante SMP framework in telecoms suggests that it arguably should have been presented as an additional option (or possibly even a replacement) to the gatekeeper options (3a and 3b) of the ex ante platform regulation. Not only is it clear that Option 2 of the NCT more closely resembles an ex ante regulatory intervention than an ex post competition tool, there is also the question of the relationship between the concepts of dominance and the definition of a gatekeeper.

In particular, it may be the case that being dominant in a market is a necessary condition for being a gatekeeper. Dominance refers to the ability to act independently of other market participants, including customers and competitors. It is open to debate whether, and in what contexts, a platform can be a gatekeeper capable of causing harm if it cannot act independently of the market participants, including users on either side of the platform.

Alternatively, the Commission may be conceiving of gatekeepers as large platforms having a position of power relative to smaller trading partners, such that they could impose trading conditions that would not be observed in normal market circumstances. This would be similar to the concept of economic dependence that exists in some EU member states’ competition law, which effectively lowers the threshold of intervention to situations of ‘relative dominance’ (i.e. a position of power relative to a trading partner) rather than ‘absolute dominance’ (i.e. a position of power across a relevant market as a whole).

The Commission cites a number of factors and criteria that may be used to determine when a platform is deemed to be a gatekeeper. Interestingly, being dominant, or even having a position of economic dependence vis-à-vis trading partners in a market, does not appear to be one of them.

Given the potentially highly intrusive nature of the remedies that could flow from a gatekeeper finding, including per se prohibitions on practices (blacklisting), it is crucial to clarify how the definition of a gatekeeper can be aligned with well-understood concepts such as dominance and SMP. This is particularly important as the Commission has said that it may take inspiration from the telecoms sector regulatory framework in the design of remedies, but, as noted above, remedies in telecoms can only be imposed with a finding of SMP.9

Inspiration from the UK market investigations regime?

The other concrete regime that these proposals draw inspiration from is the UK market investigations regime. In place since the early 2000s, this tool has been used to probe competition issues that would not be caught under Articles 101 and 102 (or their national equivalents). Indeed, the UK market investigations regime is specifically aimed at addressing gap #3, i.e. harm that is already happening due to structural market failures.

In order to be able to impose remedies under the market investigations regime, the UK authority must be able to demonstrate the existence of an adverse effect on competition (AEC), defined as ‘any feature, or combination of features, of each relevant market [which] prevents, restricts or distorts competition in connection with the supply or acquisition of goods or services’.10

In terms of the options proposed by the Commission, Option 3 of the NCT is the one that most closely resembles the UK market investigations regime. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss whether this option is appropriate to address the perceived concerns regarding the digital sector. Much will depend on what is the precise threshold for finding evidence of harm and adverse effects, as well as the standards of judicial review and appeal that investigated firms will have recourse to.11

If they are set at levels equivalent to what currently exists under EU competition law, this could become an important new tool in DG Competition’s armoury. There is a risk, however, that the new tool is designed to address not only harm that is already happening due to structural market failures and can therefore be evidenced (gap #3), but also harm that is hypothesised to happen in the future due to structural features of the market (gap #2).

In the latter case, this would go well beyond the scope of the UK’s market investigations regime and start to resemble the prospective analysis that is required under the significant impediment to effective competition (SIEC) test in merger control. The key difference is that, unlike merger control, there would be no concrete transaction or change in market structure to focus the analysis on.

Competition and fairness: friends or foes?

A close read of the NCT and ex ante platform regulation proposals reveals that they are in pursuit of both competition (economic efficiency) and fairness as policy goals.

There can, however, be some tension between these two objectives, depending on how one defines fairness. Commissioner for Competition Margrethe Vestager articulated this well in her speech at the 2018 GCLC Annual Conference:12

[…] [I]n the end, that’s what the competition rules are for […] to make sure that our markets stay competitive enough to give consumers the power to demand a fair deal. [But] [i]t doesn’t mean that just because something is unfair, it’s automatically also against the competition rules.

As explicitly stated in many publications, the Commission considers that the position of some online platforms may have become so strong that they are able to impose unfair commercial conditions on businesses that have become economically reliant upon them. This was indeed one of the prime motivations for the P2B Regulation, which recognised that any imbalances of bargaining power will not necessarily be resolved for all customers by more competition, nor are they necessarily caused by structural competition problems.

Furthermore, the P2B Regulation recognises that many terms and conditions that may appear unfair from the perspective of one party, are actually central to the functioning of the platform and therefore create significant value and efficiencies for the system as a whole. As a result, the P2B Regulation does not ban practices, nor limits commercial and contractual freedom. Instead, it requires transparency and other safeguards for business users of platforms.

In any discussion of fairness, it is important to recognise that it is a relative concept with various different dimensions (as we discussed in a previous Agenda article).13 In particular, fairness might relate to the process or the outcome.

If fairness focuses on the process, there is less likely to be a tension between fairness and competition objectives, since, for example, fair processes tend to involve higher transparency, which in turn promotes competition. However, if the concept of fairness primarily focuses on the outcome, there can be a tension with competition law, because there are likely to be many instances where practices could be considered to be pro-competitive due to long-run dynamic efficiency reasons but they could be perceived to be unfair to a group of customers in the short run. For example, price discrimination can be efficient (especially when it leads to a market expansion and the recovery of risky investment costs), but under the lens of ‘fair outcomes’ it might be seen as unfair to charge different prices to different consumers for the same good or service.

In this regard, some of the more interventionist proposals by the Commission (such as blacklisting practices) appear to be guided more by the desire to achieve a certain fairness in outcome. A concern with such an approach is that it runs a high risk of adopting a partial view of fairness, without taking into account the efficiencies and value created, for both consumers and business users, by different platforms’ business models and their practices.

For example, a key concern of the Commission is that platform markets might ‘tip’ to one player. However, being large is often central to the platform business model. Indeed, such tipping, where it occurs, is often the result of network effects, which give rise to significant efficiencies and value for the users of the platform. Tipping happens because consumers and/or businesses prefer to be on platforms that other consumers or businesses are using, regardless of whether these are one-sided or multi-sided platforms.

Furthermore, platform markets prone to tipping are also arguably more likely to remain contestable relative to traditional natural monopolies. Indeed, such platforms still need to ensure that they remain attractive to their users at all times, since the presence of network effects means that networks can implode as rapidly as they can explode.14 A close case-by-case examination of different platforms’ business models and their competitive dynamics will therefore be required to make a proper assessment of the overall fairness of current and future market outcomes.

1 European Commission (2020), ‘PROPOSAL FOR A REGULATION: Digital Services Act package – ex ante regulatory instrument of very large online platforms acting as gatekeepers’.

2 European Commission (2020), ‘PROPOSAL FOR A REGULATION: Digital Services Act – deepening the internal market and clarifying responsibilities for digital services’.

3 European Commission (2020), ‘PROPOSAL FOR A REGULATION: Single market – new tool to combat emerging risks to fair competition’.

4 These include structural risks to competition (i.e. the market may be about to tip); and structural lack of competition (i.e. high concentration, entry barriers and consumer lock-in). For example, the Commission could use the NCT to intervene in markets that it perceives as at risk of ‘tipping’ and it could also intervene in (unilateral) practices by non-dominant firms in an oligopolistic market.

5 The concerns noted by the Commission include: the economic dependence of traditional businesses on large platforms; difficulties for innovative startups to compete due to the incontestable position of some large platforms; and the ability of the large platforms to enter adjacent markets with relative ease and the risk that those adjacent markets tip towards them as well.

6 The criteria used as examples do include the presence of significant network effects; the size of the user base; and the ability to leverage data across markets.

7 These might be principles-based, applying to gatekeepers in whichever sector they operate (e.g. ban on self-preferencing in all markets in which the gatekeepers are present); and/or issue-specific rules for particular markets or practices (e.g. operating systems, algorithmic transparency, online advertising).

8 This was justified at the time, given that the telecoms sector had been recently liberalised and many of the largest players were formerly state-owned monopolies. Hence, a tool that allowed regulators to act quickly to prevent harm as well as to actively promote competition was seen as crucial for the future development of the sector.

9 ‘While recognising the many differences, experience from the targeted and tailor-made ex ante regulation of telecommunications services can serve as an inspiration in this regard, given the similarities deriving from network control and network effects.’ See p. 4 of European Commission (2020), ‘PROPOSAL FOR A REGULATION: Digital Services Act package – ex ante regulatory instrument of very large online platforms acting as gatekeepers’.

10 UK Enterprise Act 2002, Section 134(1).

11 In the UK market investigations regime, the Competition and markets Authority (CMA) carries out very in-depth economic analyses of the market for 18 months, to identify competition concerns and potential remedies rooted in empirical evidence. In a number of cases, the Competition Appeal Tribunal has in turn carried out in-depth ‘on the merits’ reviews of CMA decisions.

12 Speech on fairness and competition by Margarethe Vestager at GCLC Annual Conference, Brussels, 25 January 2018.

13 Oxera (2019), ‘Fairness and competition in online markets: friends or foes?’, Agenda, April.

14 See Oxera (2019), ‘Death of an old star…evolution of a new one?’, Agenda, February.

Download

Contact

Felipe Flórez Duncan

PartnerContributors

Related

Download

Related

Ofgem’s RIIO-3 Sector Specific Methodology Decision

On 18 July 2024, Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Decision (SSMD) for the forthcoming RIIO-3 price control period for electricity transmission (ET), gas transmission (GT) and gas distribution (GD) networks.1 This follows Ofgem’s consultation on the matter in December 2023.2 RIIO-3 will last for… Read More

The future funding of the England & Wales water sector: Ofwat’s draft determinations

On Thursday 11 July, Ofwat (the England and Wales water regulator) published its much anticipated Draft Determinations (DDs). As part of the PR24 price review, this sets out its provisional assessment of allowed revenues and performance targets for AMP8 (2025–30)—and will be of great interest to water companies, investors,… Read More