Economics of the Data Act: part 2

As the world becomes increasingly interconnected through smart devices and data-driven technologies, there challenges and opportunities presented by the data created in this process 1. Recognising this, the European Commission (EC) has introduced its Data Act, a landmark regulation designed to set clear guidelines for accessing and using data generated by Internet of Things (IoT) devices. By fostering enhanced data sharing, the Data Act aims to boost innovation, competition and a more dynamic digital economy.2

From 12 September 2025, all IoT data holders will be required to comply with the new legislation.3

In the first article of our series on the Data Act, we examined its broader implications for business-to-business (B2B) data sharing and its role in the EC’s strategy to establish a single market for data. We also highlighted how the Data Act interacts with other pieces of legislation such as GDPR and the DMA. In this second article, we shift our focus to the practical aspects of compliance, offering key considerations for businesses before they enter into a data-sharing contract.

While data sharing presents significant opportunities for growth and innovation, navigating the Data Act’s obligations can be complex for both data holders and recipients. If you are preparing for compliance, you may be wondering: what does this legislation mean in practice? To provide clarity, the Commission’s guide, ‘Data Act explained’, outlines key considerations for B2B data sharing.4 But is this clear enough? Some companies and industry associations have expressed concerns about the lack of clarity and uncertainty regarding compliance.

In this article, we set out the economic principles that shape the interpretation of the following B2B data-sharing obligations. In particular, we focus on the following three stipulations:

- Data may not be shared with a third party to develop a competing product.5

- Data holders may request reasonable compensation for making data available to a data recipient. 6

- Data holders may refuse to share data if they are highly likely to suffer serious economic damage from the disclosure of trade secrets. 7

To illustrate these principles, we present a fictional case study on SustainDrive, an imaginary company specialising in electric vehicle (EV) technology that reduces energy consumption. Through this lens, we explore how businesses can navigate data-sharing agreements in order to achieve compliance while protecting their business interests.

Data may be shared to develop a competing product

In our first article we explained that a company that has been designated as a ‘gatekeeper’ in the Digital Markets Act cannot request or be granted access to users’ data. The Data Act imposes another exclusion—it prohibits third parties from gaining access to data to develop competing products:

‘the user shall not use the data […] to develop a connected product that competes with the connected product from which the data originate.’8

In practical terms, this means that data received may be used only to improve and develop products and services in markets that are distinct from where the data originated.

Therefore, while the answer to the question of whether a data holder must grant access to users’ data to any third party is ‘no’, a detailed assessment will need to be undertaken to determine whether a particular request should be granted. Such an assessment would need to determine (i) for which products the third party intends to use the data; and (ii) whether the products for which the data will be used are in competition with the product from which the data originates.

While the concept of competition is familiar to any business, the way in which this is defined in the context of the Data Act is likely to represent unfamiliar territory.9 The EC has yet to indicate which method will be used to define competing products in the context of the Data Act, but it is likely it will use a tool commonly used in competition policy to identify and define the boundaries of competition between undertakings, referred to as defining ‘the relevant market’.10

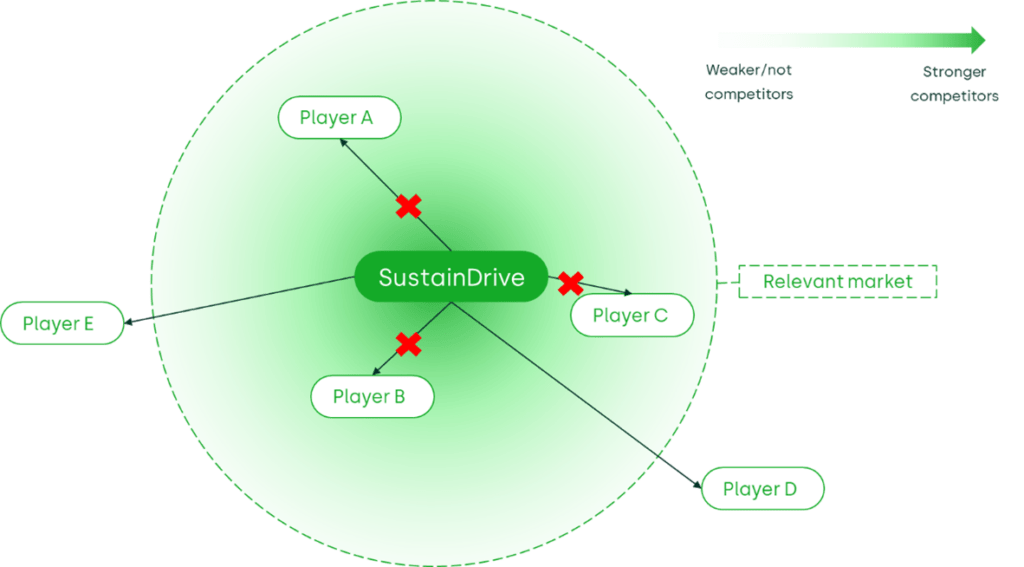

The goal of such a market definition exercise is to carefully examine the competitive pressure exerted by different products on each other.11 This involves assessing the degree to which one product can substitute for another (see the illustrative example in Figure 1).12 While it may be obvious for many products, the process of market definition can prove to be a complex exercise for others.13

Figure 1 Relevant market definition and identification of potential sharing partners

Take the example of SustainDrive. Under the Data Act, third parties will be prevented from gaining access to data generated by SustainDrive’s EV technology if this data is used to develop products that directly compete with SustainDrive’s EV technology. If a third party wants to use the data to improve a product that is not considered a competing product, i.e one that falls outside the relevant market, such as products by player E in Figure 1,sharing is not prohibited. This might for example be a car insurance provider. However, if the third party requesting data access is developing a navigation tool that, among other things, can suggest routes that consume the least energy, the players might be in competition. A more in-depth assessment may be needed to determine whether the two products compete and fall within the same relevant market. If they are found to be part of the same relevant market based on their closeness of competition data sharing is prohibited under the Data Act.

The EC relies on several economic tools when carrying out a market definition exercise. One such tool is price-correlation analysis. This involves examining whether the prices of different products move together, which can indicate that they are part of the same market.14 For example, if SustainDrive’s EVs and a third-party’s not-electrical vehicles experience similar pricing trends, this might suggest that the third party’s products could be in the same market as SustainDrive’s EVs.

Another valuable method is the SSNIP (small but significant non-transitory increase in price) test.15 This test helps to delineate the boundaries of a market by assessing whether a hypothetical price increase for a product would lead to a significant loss of customers to alternative products. For instance, if we want to test whether the relevant market comprises only electric cars or any electric means of transport, the test’s question would be: if all electric cars would increase their price, would customers switch to different electric means of transport (e.g. e-bikes)? The outcome of this test can help to determine whether the third party that produces the alternative product is operating in the same market.

A practical application of the SSNIP test is critical loss analysis, which estimates the impact of a price increase on sales to understand the competitive constraints.16 In this case, this would involve calculating how much profit (if any) would be lost if EV prices increased, and whether such a loss would indicate substantial competitive pressure from alternative products or that the data-sharing partner operates in a different relevant market.

By employing these economic tools, it is possible to define which other products operate in the market in which SustainDrive offers its EV technology, and identify which third parties should and should not be granted access to the user data.

In ‘data markets’ it is sometimes harder to assess concepts such as market definition, giving the fluid nature of data, and the fact that data is nonrival and can be used by many companies and different services simultaneously. Data markets are also highly dynamic, meaning that while initially two services might not compete, over time this might change, which is another complexity to take into account. This means that market definition in data markets may required more in-depth examination and may need to be regularly revisited

Data holders may request reasonable compensation for their data

The Data Act allows data holders to request compensation from the party receiving the data. While the price charged to SMEs receiving the data must not exceed those costs that relate directly to making the data available,17 the Data Act allows for compensation that includes a margin when recipients are large enterprises.18

When agreeing on compensation, the Data Act requires that two cost components are taken into account:19

- the costs incurred in making the data available and, in particular, the costs that are necessary for the formatting of data and its dissemination via electronic means and storage;

- the investments in the collection and production of data.

The second component is especially relevant. In the context of a regulation that is aimed at greater innovation from data, it is key that continued investment in data collection is incentivised.20

To encourage investment, any compensation will have to take into account the ‘value to the owner’ principle, which compensates the data holder for the risk of investing in the asset and the loss of exclusivity of its use. The level of compensation will depend on a number of factors, including the nature of the data.21

The Data Act has called for guidelines from the EC on the calculation of reasonable compensation in the data economy, but such guidelines have not yet been published.22 However, in other sectors of the economy reasonable and non-discriminatory pricing has been extensively discussed.

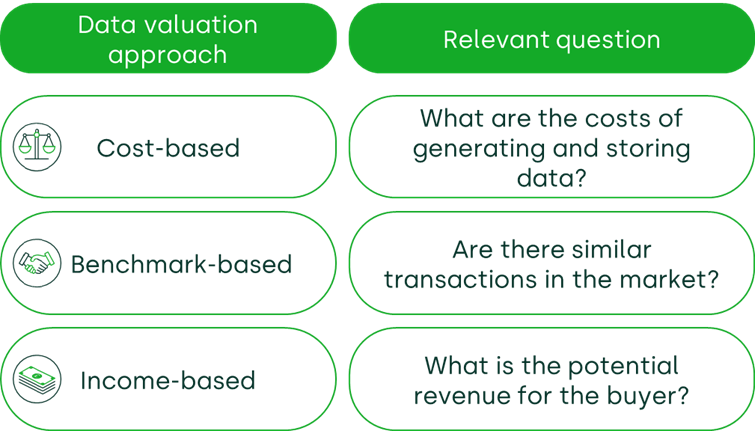

Access pricing methods discussed in other sectors can be categorised into three main approaches: cost-based, benchmark-based and income-based. They serve different purposes and should be applied on a case-by-case basis.23 In the figure below we explain how those approaches can be applied in practice and when such an approach might be appropriate.

Figure 2 Data valuation approaches

Benchmark-based approaches to data-sharing compensation

The value of data can be assessed using a benchmarking approach when comparable datasets are actively traded in the market. This approach considers both buyers’ willingness to pay and sellers’ willingness to sell, making it particularly useful when the primary concern is fair pricing. Market-based comparisons can help to evaluate the pricing strategies of similar providers or the fees charged for comparable assets. This is especially relevant for data transactions that occurred before the Data Act came into force, where prices were negotiated freely on commercial terms.

To determine a fair valuation, techniques such as average comparisons or regression analysis can isolate the impact of specific data attributes—such as volume, quality or coverage—based on previously traded datasets.

This method is widely used in intellectual property (IP) valuation, where market-based pricing benchmarks help to establish a transparent and justifiable valuation framework.

Cost-based approaches to data-sharing compensation

When no similar assets are being traded in the market, a cost-based approach may be appropriate. This approach is especially relevant when the concern or policy objective is about accessing an essential facility that cannot be replicated, and where innovation or incentivising future investment is unlikely.

In the context of the Data Act, this could be interpreted as data that is difficult to obtain through any other means. For instance, any data on SustainDrive’s battery performance under diverse driving conditions is unlikely to be accessible from anywhere other than data generated by those batteries. Location data, on the other hand, is more widely available. As such, a cost-based approach is likely to be more appropriate when valuing data on SustainDrive’s battery performance under diverse driving conditions than location data.

If using a cost-based approach, SustainDrive should calculate the costs involved in generating and sharing its battery performance data. As part of such an assessment, SustainDrive would need to identify:

- direct costs, such as the costs of storing, processing and sharing the data;

- indirect costs, including the costs of investment in the battery itself, without which no performance data could be generated.

A key challenge in this approach is the allocation of indirect costs. While it would be incorrect to attribute all battery development costs to the generation of performance data, some portion of the investment should be considered. Determining a fair allocation method is complex, as various methodologies exist—and the most appropriate one depends on the context and purpose of producing cost estimates.24

A commonly used costing approach when considering prices for access to a downstream supply chain is the calculation of the long-run incremental cost (LRIC). This method is widely used to determine access to telecoms infrastructure. In the context of the Data Act, it might be relevant when considering compensation for data that is shared with suppliers in aftermarket services.

Income-based approaches to data-sharing compensation

The income-based approach considers the revenue that the data could generate for the recipient. This approach is particularly useful when there are concerns about the distribution of economic value among parties, as it allows for a bottom-up estimation of future revenues based on how the data is used across various business activities.

If a recipient uses SustainDrive’s data to improve their EV charging stations, the expected increase in profits can help to inform a fair price for the data by making sure that the price reflects the data’s contribution to the buyer’s revenue growth.

This method involves estimating the asset’s incremental value relative to its next best alternative. For instance, SustainDrive could evaluate the incremental value of its battery performance data by comparing the potential gains for a charging station manufacturer using its data versus data from another source. The value difference between these two sets of data will help SustainDrive to set a fair price.

In summary, which of the three methods is appropriate to determine reasonable compensation for data sharing depends on the context. What reasonable compensation looks like will depend on answers to the following questions: what is the cost associated with the data? Are there other types of wider value being generated by the use of such data? What is the data worth to the different (current and potential) users?

Data holders may be exempt from sharing if it results in serious economic damage

While gaining access to data can drive innovation and growth, sharing data that contains trade secrets can have significant implications and risks for businesses. The Data Act considers that, with the right protections and security measures in place, such risks are rare. Nonetheless, the Data Act allows for data-sharing exemptions if a data holders can demonstrate that it is highly likely to suffer serious economic damage from the disclosure of trade secrets.25

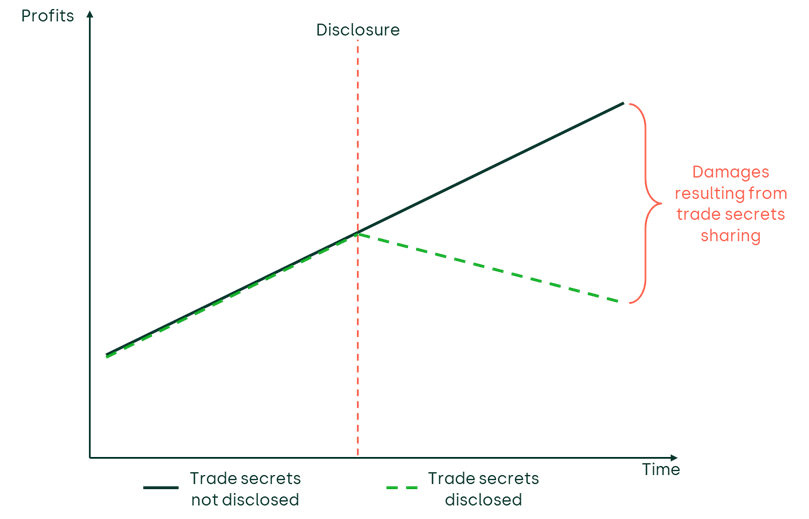

The calculation of economic damage is frequently undertaken in litigation cases, including commercial disputes and antitrust cases, and relies on a well-established framework. In this framework, damage is calculated by comparing a hypothetical scenario in which the harmful event has not taken place (the ‘but for’ or counterfactual scenario) with the factual scenario. The difference between the two scenarios in terms of economic value is the damage arising from the harmful event. In this context, given that the economic damage is calculated ex ante, this would involve building a counterfactual scenario in which the harmful event does take place—a ‘what if’ scenario.

Figure 3 Assessment of damages from trade secrets sharing

What is the relevant benchmark for the counterfactual?

A central component of any damage calculation is therefore the counterfactual scenario. To establish a meaningful counterfactual, it is important to identify an appropriate benchmark: how is economic value measured? When the harmful event results in damage to businesses, this is typically assessed using profitability metrics. Valuation is closely linked to profitability, as the value of a company or asset generally reflects the expected future returns that it can generate.

Three broad methods can be used to estimate economic damage from a trade secret:26

- the cost-based method;

- the income-based (or cash flow-based) method;

- the market-based (or comparator-based) method.

The suitability of each method depends on the specific context of the damage assessment, as each comes with its own strengths and limitations. The cost-based method focuses on the expenses incurred in developing or maintaining a trade secret, but does not capture the revenue or profit potential that the secret may generate and may thus understate its real economic value to the business. The market-based method critically relies on comparing similar events happening to similar companies, which can be particularly difficult due to the inherently confidential and unique nature of such assets. The income-based method requires a projection of future cash flows attributable to the trade secret—an exercise that often involves high levels of uncertainty.

When selecting the appropriate damage estimation method, it is relevant to keep in mind what a trade secret is and how it affects financial performance. A trade secret confers on a business a competitive advantage that is expected to generate incremental revenues relative to a situation in which the trade secret is disclosed. Losing this competitive advantage is likely to result in more intense competition and a decrease in revenues. As such, establishing financial performance in the counterfactual would involve an assessment of how the loss of a trade secret would affect revenues and profit margins. Given this focus on future earnings, the income-based method is likely to be a suitable approach for evaluating damages resulting from the disclosure of a trade secret.

In the case of SustainDrive, the disclosure of trade secrets such as proprietary methods to extend battery life, reduce degradation or improve charging speed could result in lower barriers to entry for new competitors or stronger competition from existing competitors. As a result, the business might experience lower revenues due to downward pricing pressure or lower volume.

In this case, a detailed financial model with projected profits in the factual and in the counterfactual could be used to determine the damage resulting from the loss in profits if competitors gained access to its proprietary technology.

Conclusion

As businesses prepare for the implementation of the Data Act, navigating its requirements around B2B data sharing will be essential—not only for compliance, but also to ensure the establishment of equitable data-sharing terms. While the regulation opens up new opportunities for innovation and market development, it also places important boundaries on how data can be accessed and used, particularly when trade secrets and competition are at stake.

This article has explored how economic principles—such as market definition, compensation mechanisms and damage assessment—can guide businesses in evaluating data-sharing requests and structuring agreements. The SustainDrive case study illustrates that compliance is not just a legal matter but also an economic one, where careful analysis is required to assess risks, define markets and quantify value.

Ultimately, successful data sharing under the Data Act requires a balanced approach—one that supports collaboration and innovation, while safeguarding investments related to data. By applying established economic frameworks, businesses can better understand and respond to the obligations introduced by the Data Act. These principles recognise that, while data sharing may bring benefits, it also raises complex questions around value, risk and competitive dynamics that require careful, context-specific analysis.

Footnotes

1 European Commission (2024), ‘European Data Act enters into force, putting in place new rules for a fair and innovative data economy’, 11 January

2 European Commission (2024), ‘Shaping Europe’s digital future: Data Act’, 10 October.

3 European Commission (2025), ‘Shaping Europe’s digital future: Data Act explained’.

4 European Commission (2025), ‘Shaping Europe’s digital future: Data Act explained’.

5 European Parliament (2023), ‘Regulation (EU) 2023/2854 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 2023 on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data and amending Regulation (EU) 2017/2394 and Directive (EU) 2020/1828 (Data Act) (Text with EEA relevance)’ (’Data Act’), Article 4 (10).

6 Data Act, Article 9 (1) and (4).

8 European Parliament (2023), ‘Regulation (EU) 2023/2854 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 2023 on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data and amending Regulation (EU) 2017/2394 and Directive (EU) 2020/1828 (Data Act) (Text with EEA relevance)’ (’Data Act’), Article 4 (10).

9 Graux, H. (2022), ‘Sharing Data (Anti-)Competitively: Will European data holders need to change their ways under the proposed new data legislation?’, European Commission data.europa.eu studies.

10 European Commission (2024), ‘Commission Notice on the definition of the relevant market for the purposes of Union competition law’, para. 6.

11 The Data Act itself recognises that, to determine whether two products are in competition with each other, established principles of Union competition law should be used. Source: Data Act, p. 11, para. (32).

12 This question is valid both for consumers and for suppliers.

13 Niels, G., Jenkins, H. and Kavanagh, J. (2023), Economics for Competition Lawyers, third edition, Oxford University Press, para. 3.1.1.

14 Niels, G., Jenkins, H. and Kavanagh, J. (2023), Economics for Competition Lawyers, third edition, Oxford University Press, para. 3.3.12.

15 Niels, G., Jenkins, H. and Kavanagh, J. (2023), Economics for Competition Lawyers, third edition, Oxford University Press, para. 3.3.

16 Niels, G., Jenkins, H. and Kavanagh, J. (2023), Economics for Competition Lawyers, third edition, Oxford University Press, para. 3.4; or Oxera (2008), ‘“Could” or “would”? The difference between two hypothetical monopolists’, Agenda, November.

18 Data Act, Article 9 (1) and (4).

23 For further examples of data valuation methods, see Oxera (2021), ‘If data is so valuable, how much should you pay to access it?’, Agenda, February.

24 See Oxera (2025), ‘Allocation of indirect costs’, Agenda, March.

26 See also Oxera (2016), ‘Putting a price on ideas: how can intellectual property be valued?’, Agenda, August.

Contact

Lola Damstra

Senior ConsultantContributors

Related

Related

Financing the green transition: can private capital bridge the gap?

The green transition isn’t just about switching from fossil fuels to renewable or zero-carbon sources—it also requires smarter, more efficient use of energy. By harnessing technology, improving energy efficiency, and generating power closer to where it’s consumed, we can cut both costs and carbon emissions. In this episode of Top… Read More

A map of AI policies in the EEA and UK

Oxera offers an overview of AI-related policies in EEA countries and the UK through an interactive map. This AI Policy Map allows users to follow developments in AI regulation and examine national policy approaches in more detail. Artificial intelligence (AI) is driving technological change at an unprecedented pace, transforming industries,… Read More