Economics of the Data Act: part 1

As electronic sensors, processing power and storage have become cheaper, a growing number of connected IoT (internet of things) devices are collecting and processing data in our homes and businesses. The purpose of the EU’s Data Act is to define the rights to access and use data generated by IoT devices in order to encourage more data sharing.

At its heart, the aim of the Data Act1 is to enable the benefits from increased data sharing while ensuring that enough incentive is provided to IoT manufacturers to continue providing that data. It is challenging to get this balance right, and there are significant risks in getting it wrong. This article examines how the Data Act aims to strike a reasonable balance and how it interacts with other EU regulations, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Digital Markets Act (DMA).

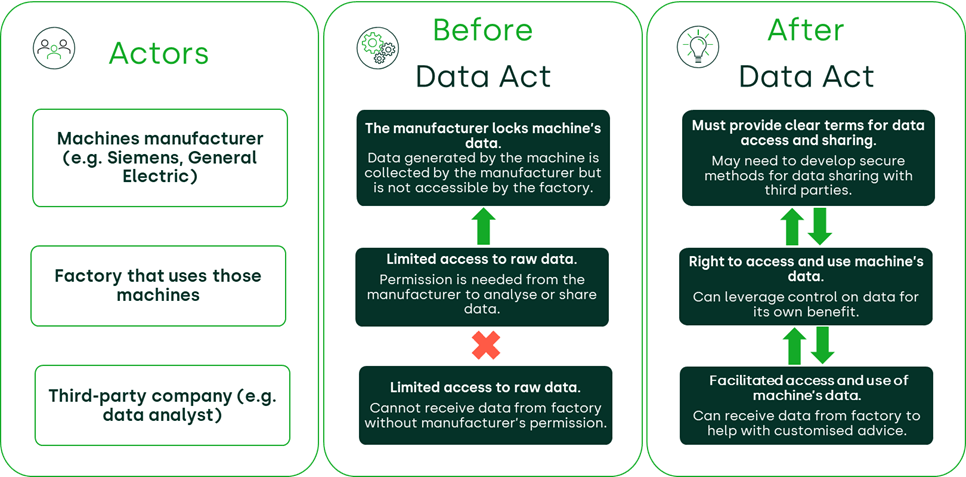

The Act aims to boost the EU’s data economy by lowering barriers to data sharing for governments and businesses and creating a more competitive market for cloud technology. It seeks to do this through the creation of rules regarding the fair access and use of data generated through connected devices (ranging from home appliances and smartphones to smart industrial machinery). The aim is to make more data available for the benefit of consumers, businesses and the wider public. According to the European Commission, the Data Act is expected to create €270bn of additional GDP for EU member states by 2028.2 Figure 1 below provides a practical example of the implementation of such rules in the context of industrial machinery.

Figure 1 An example of what will change after the Data Act

First proposed in February 2022, the Data Act is a legislative initiative comprising part of the Commission’s European strategy for data.3 The Act entered into force on 11 January 2024, and will become applicable 20 months later.4

This article discusses one of the key pillars of the Act: business-to-business (B2B) data sharing. As data is a crucial input for innovation, data access can help firms to develop cutting-edge products and services.

Barriers that currently limit data sharing between companies might include a lack of incentives for firms to voluntarily enter into sharing agreements, an uncertainty over rights and obligations relating to data, a lack of clarity about the economic value of datasets, and the presence of bottlenecks impeding data access.5

By enabling a B2B data sharing framework, the Data Act intends to achieve two objectives:

- to enable users of connected devices to access the data that is generated and the services that relate to their devices;

- to protect firms from unfair contractual terms, which are usually imposed unilaterally, and thus promote competition and even out the bargaining power across players in a market.

Although the goals of the Data Act have been set out clearly, its implementation, compliance process and ultimate impact are more uncertain. In what ways will its rules affect businesses in practice? How will a data provider be compensated for their data? What existing legislation will interact with the Data Act?

How will the Data Act work?

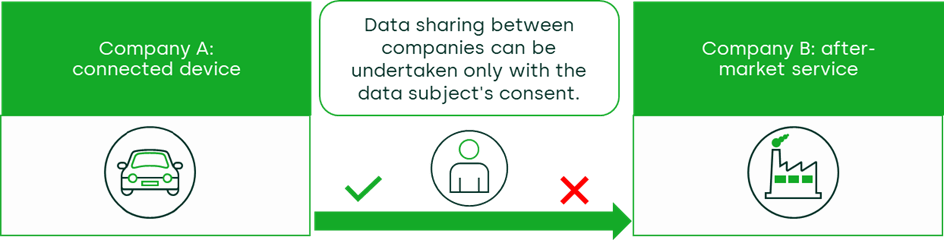

The Act requires manufacturers and service providers to allow individuals and users to access data that is generated while a product or service is used. This includes all devices that connect with, and exchange data with, other devices and systems over the internet. Users will be able to ask the data holder to share their device data with third parties, on a real-time and continuous basis. This process is illustrated in Figure 2 below. Importantly, third parties will be able to access a data subject’s data only with their consent.

Figure 2 Only the data subject can consent to data sharing

The data may be used only for products and services that do not compete with the connected devices from which it is collected. All businesses in all industries will be able to benefit from data access provisions under the Data Act, with the exception of ‘gatekeepers’ identified in the DMA.6

To illustrate the potential implications of the Act, we consider below the example of the automotive industry, where many applications are expected.

New car models have a number of built-in features aimed at improving the driving experience. These might include a built-in GPS, a crash detection system, or required maintenance notifications. They can record key information such as the car’s location, whether the vehicle has been involved in an accident, driving speed, and so on. These features, which allow a vehicle to communicate with other devices and systems, mean that it is classified as a connected device.

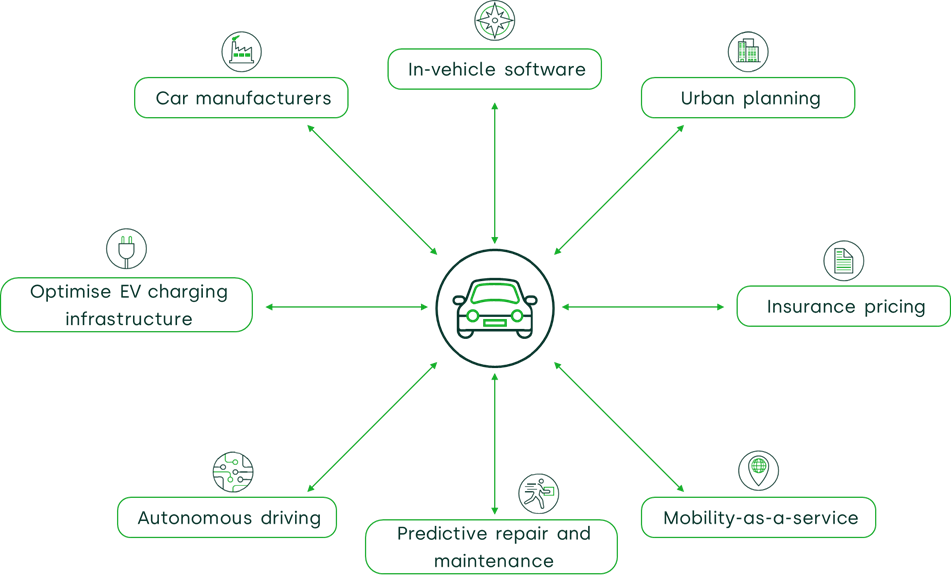

With the implementation of the Act, users of the connected vehicle will be able to choose to share the data that is held by the car manufacturer with any third party. For example, insurance companies will be able to ask their customers to grant access to data on their driving behaviour. This information would allow the insurance companies to offer products that are more in line with the risk that a particular driver faces. Examples of this and other potential applications of the Act are illustrated in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3 Illustration of third-party access to vehicle data

Third parties may also be able to access user data that benefits the wider public. For example, electric vehicle (EV) infrastructure operators would be able to improve their decision-making regarding EV roll-out by gaining access to the driving patterns of EV owners and EV battery levels. However, direct competitors, such as other car manufacturers, could be restricted from accessing data from a rival if the data could be used to compete in the same market as where the data originated.

Moreover, as the Act also covers smartphones and tablets, data could potentially be retrieved not only from the vehicle itself but also from any smartphone that is connected to it. This, in turn, could provide third parties with an even wider set of information.

What is the price for access?

It is likely that significant benefits could be realised from data sharing to the benefit of both individual consumers and wider society. However, data collection is not free, and a market for data can be achieved only if businesses have sufficient incentives to generate that data.

The price at which data access is set is therefore highly relevant if the Act is to achieve its objectives. Data must be sufficiently affordable that data recipients seek to access it, but must also appropriately reward the data provider for their role in collecting and processing it. To achieve this dual goal, the parties involved in a data transfer must agree to it on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms.

Typically, FRAND terms are applied to products that are an important input for a downstream market.7 The concept of FRAND is designed to provide a reasonable return for producers such that it preserves their incentives to continue innovating, while simultaneously preventing providers from profiting unreasonably from the removal of competition by foreclosing access to the market with higher prices. FRAND terms must therefore satisfy two opposing objectives:

- access to a relevant input—in this case, product data and related service data;8

- continued provision of that input.

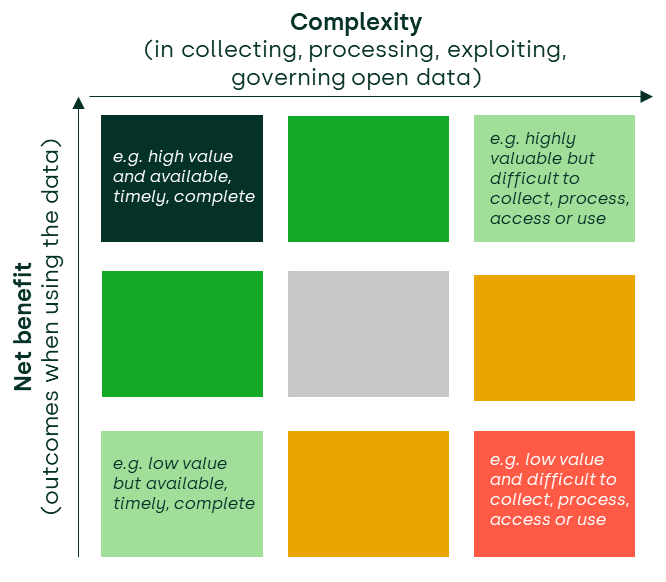

The actual FRAND price will be determined on a case-by-case basis as data is not homogenous—the value that a recipient can derive from the data that it obtains will vary greatly, and hence so will the FRAND price. Figure 4 below is a matrix depicting how the value of data is maximised when the net benefit is high but the complexity is low. Hence, data is most valuable to the recipient when it sits in the upper-left box of the matrix. This symbolises the point where the data provider collects, processes and governs the data with minimal complexity, minimising costs for itself and simplifying the exploitation process for the recipient. The user then obtains a large net benefit from the data, such as being able to deliver more personalised and higher-quality products or services to its customers.

Figure 4 Data value matrix

In a situation where a data recipient obtains data, the FRAND price would generally cover the direct costs borne by the data provider as well as investments made for the data collection, thus maintaining incentives for continuing high-quality data collection.9 This is another crucial aspect of FRAND terms: they allow for a positive margin such that data providers have incentives to further fund data processes, bolstering innovation and continually reducing data complexity.10 Additionally, the recipient will feel justified in fairly compensating the provider due to the net positive outcome that the data will help them to achieve.

The right access price is thus one that promotes competition, but also sufficiently compensates data providers for continuing to provide the underlying data. FRAND pricing seeks to do this, but this pricing principle does not come without its challenges. Setting a FRAND price requires either a large amount of evidence or judgement, and, as has been pointed out elsewhere, negotiations over access prices are likely to result in court appeals, which could slow the impact of the Act.11 This process may be simplified in the future with Guidelines from the Commission, as anticipated in the Act.12

However, more certainty over the right access price is given for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) and not-for-profit organisations. The Act spells out that, for these categories of data recipient, the price shall not exceed the direct costs of data provision.13 This pricing approach is known as ‘price equal to marginal cost’, where the price is set at the additional cost to the data provider of making the data available with no opportunity to make a profit margin. This asymmetric regulatory approach has been proposed by the Commission to tackle the digital divide between MSMEs and larger companies, and to give balanced opportunities for all to benefit from the power of data.14

How does the Data Act fit in with the wider regulatory landscape?

The Act sits alongside a number of other legislative pieces that are part of the Commission’s strategy for data and aim to create a single market for data.15 These regulatory provisions unavoidably overlap in a number of ways, and the Act underlines the requirement that existing regulation preceding the Act must prevail. This means that the Act must be interpreted in conjunction with these other pieces of legislation.

In particular, the Act to some extent overlaps with the GDPR, which came into force in order to protect personal data.16 The interplay between the GDPR and the Act is particularly interesting because, although they are often complementary, there are tensions between their objectives. The GDPR is designed to guarantee protection of the fundamental right to privacy. It includes a number of principles outlining how data is managed and stored, one of which is data minimisation. This means that, by default, only personal data that is necessary for each specific purpose of the processing is actually processed. To ensure compliance with the GDPR, connected devices must be built to ensure that data collected on a device that is not necessary for a specific purpose is anonymised, pseudonymised, aggregated or kept private on the device.

In contrast, the Act allows users to request all data collected by the device that is necessary for the provision of the service requested by the user. To ensure compliance with the Act, a device should be able to permanently store all data or, alternatively, be able to re-associate data with a specific user, so that it can be shared with third parties if requested. As a result, it will be important to understand how to adhere to the data minimisation principle under these two pieces of regulation.

The Act also makes direct reference to the DMA. The DMA seeks to limit the competitive advantage of large digital providers that serve as gateways for their business users and consumers, referred to as gatekeepers.17 Gatekeepers are defined in the DMA as those bodies ‘providing core platform services’ with ‘considerable economic power’ and meeting certain predefined criteria. Currently, Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Bytedance, Meta and Microsoft have been designated as gatekeepers.18 The regulation requires them to give third parties and end-users access to different types of data, and restricts how these companies can collect and use data from their services.19 The DMA’s definition of gatekeepers has been used in the Act to prevent gatekeepers from gaining access to data due to their ‘unrivalled ability’ to do so.20 Some of the DMA provisions that regulate data sharing from core platform services have different conditions from the Data Act provisions on the same topic. This implies that there might be instances where gatekeepers will not be allowed to access data using the Act, but are allowed to access the same data under the DMA.21

Get ready to be Data Act compliant!

The final text of the Act was published at the end of 2023 and entered into force during January 2024. The next stage is for it to be enforced by EU member states. As the Act is a complex piece of regulation, there will be many aspects to bear in mind when implementing and interpreting it. This article has shed light on some of its key principles.

In the next article of this series we will delve deeper into how businesses can assess the requirements of the Act. We will discuss the methodology behind identifying the right FRAND price, how to define whether third-party access seekers supply a competing product, and tools to investigate whether a company can refuse to share data on the basis that it contains trade secrets and sharing it could have a significant detrimental effect on its business.

1 European Commission (2023), ‘Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data (Data Act)’, 13 December, p. 4, para. 14.

2 European Commission, ‘European Data Strategy’.

3 European Commission (2022), ‘Data Act: Commission proposes measures for a fair and innovative data economy’, press release, 23 February.

4 European Commission (2023), ‘Data Act: The European Commission has reached a political agreement on the European Data Act’, 29 June.

5 European Parliament (2023), ‘Data Act: Amendments adopted by the European Parliament on 14 March 2023 on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data’, 23 November.

6 European Commission (2023), ‘Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data (Data Act)’, 13 December, Article 5(3), p. 40.

7 A downstream market is one that is related to the original market, but occurs at stages further down in the supply chain.

8 European Commission (2023), ‘Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data (Data Act)’, 13 December, Article 1(1), p. 32.

9 Orrick (2024), ‘European Data Act: Harmonised Rules on Fair Access to and Use of Data’, 1 February.

10 European Commission (2023), ‘Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data (Data Act)’, 13 December, Article 9(1), p. 43.

11 CERRE Think Tank (2023), ‘Data Act: How to Finalise the Negotiations?’.

12 European Commission (2023), ‘Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data (Data Act)’, 13 December, Article 9(5), p. 43.

13 Ibid., Article 9(4), p. 43.

14 Ibid., p. 1.

15 European Commission (2020), ‘The European data strategy: shaping Europe’s digital future’, February, p. 1.

16 European Commission (2016), ‘Regulation 2016/679 of the European Parliament and Council on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation)’, Official Journal of the European Union, 4 May.

17 European Commission (2020), ‘Impact Assessment Report on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector (Digital Markets Act)’, 15 December, p. 7.

18 European Commission (2023), ‘Commission designates six gatekeepers under the Digital Markets Act’, 6 September.

19 Clifford Chance (2023), ‘The EU Data Act proposal: data access’, 2 May.

20 European Commission (2023), ‘Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on harmonised rules on fair access to and use of data (Data Act)’, 13 December, p. 26.

21 DMA, article 6(9).

Contact

Lola Damstra

Senior ConsultantContributors

Related

Related

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

The National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) has published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED31 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure that the distribution network is strategically reinforced in preparation… Read More

Leveraged buyouts: a smart strategy or a risky gamble?

The second episode in the Top of the Agenda series on private equity demystifies leveraged buyouts (LBOs); a widely used yet controversial private equity strategy. While LBOs can offer the potential for substantial returns by using debt to finance acquisitions, they also come with significant risks such as excessive debt… Read More