Decarbon-nudge?

Decarbonisation is one of the largest challenges facing societies across the world, and consumer behaviour has an important role to play in achieving this goal. Behavioural economics shows us that consumer behaviour can be influenced by ‘nudges’ and choice architecture. So what role can nudges play in helping us to decarbonise?

Under the COP26 Glasgow Climate Pact, national governments from across the world have committed to limiting global warming to under 2˚C, partly through achieving net zero carbon emissions in the next few decades.1 Reaching net zero will entail large changes to the way each sector of the economy operates—to minimise carbon emissions where possible and fund offsetting where a reduction to zero is not feasible.2 Many developed countries are market economies, where value is created through businesses responding to consumer demand. In this system, consumer behaviour has the power to change the behaviour of individual businesses and whole sectors, as firms compete to offer the best services and products to consumers (given their preferences).

So to what extent can we decarbonise through encouraging consumers to prefer low-carbon options? Can we materially change the behaviour and consumption patterns of consumers and citizens to be lower carbon? Or should we focus our efforts on more interventionist solutions, such as taxes and subsidies?

How do we change the choice architecture?

Behavioural economics tells us that we all make decisions subject to ‘cognitive limitations’, often using mental shortcuts to conserve cognitive effort. The result of these mental shortcuts is that the framing of a decision—the so-called choice architecture—matters. Altering the choice architecture, without removing options, is known as a ‘nudge’.3

Such nudges could be applied to choice of transport mode (e.g. encouraging cycling), household energy consumption (e.g. installing energy-efficient appliances, lightbulbs), food consumption (e.g. reducing meat eating), and many other domains.4 The examples in this article focus on household energy consumption.

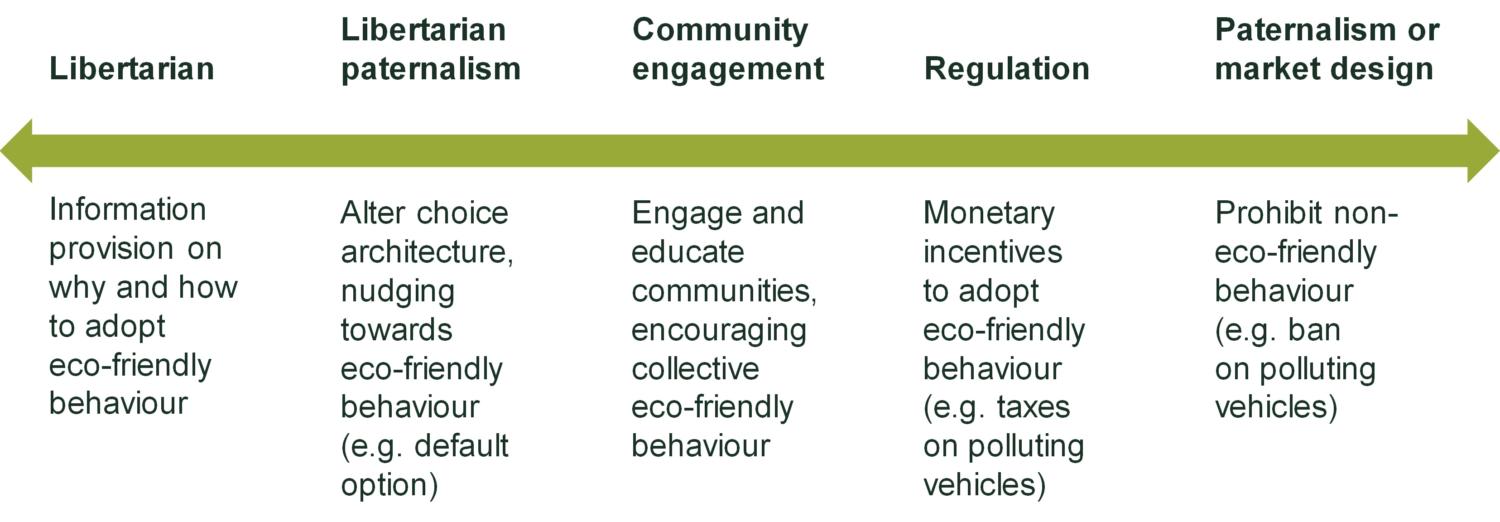

As always, there is a range of possible remedies available to regulators. This is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 The behaviour change toolkit

Given the wide toolkit of options, we need to know how effective nudges are at encouraging consumers and citizens to decarbonise. Next, we explore when nudges are typically successful in changing behaviour, and then the evidence on nudging to reduce carbon emissions in particular.

When are nudges typically successful?

There is a growing meta-analysis literature that analyses the results of past studies to draw conclusions about which types of nudge are more effective in changing consumer behaviour.

Various ways of categorising different types of nudge have been proposed in the literature.5 For the purposes of assessing the effectiveness of nudges, we can categorise nudges according to whether they target ‘fast’ System 1 or ‘slow’ System 2 thinking (see here6 for a description and critical review of the model).

Beshears and Kosowsky (2020) categorise nudges as follows:7

- nudges that seek to trigger System 1, by invoking a fast, intuitive response—for example, through arousing emotion, harnessing a bias, or simplifying the process;

- nudges that seek to engage System 2, by prompting reflection, planning and broader thinking, or by increasing accountability, or by using reminders;

- nudges that seek to automate some aspect of decision-making, bypassing both systems, by setting the default option.

The meta-analysis in Beshears and Kosowsky (2020) finds that nudges that seek to automate some aspect of decision-making are on average more effective at changing behaviour than nudges that target Systems 1 or 2. This finding is confirmed by the meta-analysis of Hummel and Maedche (2019), which finds that default option nudges are on average more effective than other types of nudge.8

The meta-analysis by Luo, Soman and Zhao (2021) found that nudges aimed at reducing the effort in decision-making were the most effective at changing behaviour.9 Such nudges could be considered as triggering System 1 or automating some aspect of decision-making.

Another recent meta-analysis by Mertens et al. (2022) also found that nudges that change the ‘decision structure’—such as defaults—were the most effective type of nudge at changing behaviour.10

Therefore, we can conclude that the most effective nudges are typically those that make the desired behaviour easiest or automatic, with default options being a prime example. The box below describes how to design an effective default nudge.

How do we design an effective default nudge?

It is important to recognise that context matters, and default options are not always effective at changing behaviour. Jachimowicz et al. (2019) find that default options are more likely to be effective at changing behaviour when:11

- the default option implies an endorsement from a trusted choice architect, or the default option reflects the status quo;

- changing away from the default option is less easy;

- prior preferences are less strongly held.

It is worth noting that there is a debate over whether default options are more or less effective in an environmental context than in other contexts (e.g. financial decisions, health, etc.). The meta-analysis conducted by Jachimowicz et al. (2019) found that default options are less effective regarding environmental behaviour. Jachimowicz et al. (2019) hypothesised that this is because attitudes about the environment might be held more strongly (i.e. those holding anti-environmentalism attitudes may be less likely to be swayed by a nudge). It is possible that this is because some of the studies analysed were conducted a number of years ago, when anti-environmentalism attitudes may have been more prevalent.

Indeed, more recent meta-analysis conducted by Mertens et al. (2022) found that decision structure nudges were actually more effective for environmental behaviour than for financial behaviour, and no less effective than for health behaviour.12 Further, Mertens et al. (2022) found that decision structure nudges are the most effective type of nudge for changing environmental behaviour. For examples of default options being effective in an environmental context, see, for example, the review by Sunstein and Reisch (2014).13 It appears, then, that default options are powerful in an environmental context.

It is a common theme in the literature that greater personalisation of nudges is likely to increase the effectiveness of nudges.14 This points to the opportunity to use behavioural data science in designing nudges that harness consumer heterogeneity (rather than being hampered by it).

Last, when designing nudges it is useful to consider the specific lessons learned from failed nudges (on which there is also a growing literature).15 Some nudges backfire because the choice architect has not fully considered how people will react. For example, some nudges attempt to discourage undesired behaviour (e.g. driving to work) by emphasising the frequency of the undesired behaviour, and in so doing inadvertently reinforce the unhelpful social norm (e.g. that driving to work is the norm).16 Alternatively, some nudges are ineffective because people face external constraints unaddressed by the nudge. For example, a nudge to encourage people pay off their credit card debt may be effective in the short term, but ineffective in the long term if people face the same budget constraints.17

Do nudges actually help decarbonise?

There are numerous positive examples of where nudges have changed consumer behaviour towards reducing carbon emissions—see, for example, Bujold et al. (2020).18 Below are three such examples.

- In Minnesota, an energy provider sent customers reports on how to conserve energy, which included social comparisons on energy use with their neighbours.19 The average treatment effect of the reports was to reduce household electricity consumption by 2%. A follow-up study found that after the reports were delivered for two years and then ceased, the reduction in energy usage continued, with the reduction in energy usage decaying at 10–20% per year.20

- In the German town of Schönau, a local environmental initiative runs the town’s electricity grid and local energy provider, and changed the energy default to (more expensive) green sources in 1998. Eight years later, in 2006, 99% of households still received their energy from this source.21

- In California, sending households framed messages about how reducing energy usage is good for human health (i.e. less pollution leading to reduced risk of asthma and cancer) was found to reduce energy consumption by 8–10% after three months, whereas information about how reducing energy usage leads to cost savings had no effect on energy consumption after three months.22

Nisa et al. (2019) conducted a meta-analysis of demand-side interventions to promote environmentally friendly behaviour.23 The study found that behavioural interventions on average result in a 2–3% probability of changing an individual’s behaviour. However, these researchers used a broad definition of behavioural interventions (i.e. including non-nudge interventions, such as information provision). When focusing on nudge interventions, the probability of changing an individual’s behaviour was greater than 2–3%, although Nisa et al. (2019) did not conclude on just how effective nudges are, given that the studies about nudges are more likely to have an element of participant self-selection (which might be expected to skew the results).

Nisa et al. (2019) also conclude that there appears to be evidence that behavioural interventions are more effective when targeted one-off behaviour (e.g. the purchase of home appliances) than recurring behaviour. This is because changing recurring behaviour typically involves changing a habit, which can be more ingrained and therefore harder to alter.

What about the costs of nudging?

Nudges are typically inexpensive to implement, meaning that even if the benefits are marginal, the net benefit of introducing the nudge may still be positive.

Benartzi et al. (2017) calculate the cost of implementing policies to reduce energy consumption (in kilowatt hours).24 They show that for the nudge implemented by Allcott (2011), as described above, energy consumption reduced by 27.3kWh for every $1 spent on implementing the nudge. This was a higher benefit per $1 spent than the two policies evaluated by the authors that used financial incentives (i.e. not nudges) (up to 14skWh saved per $1 spent).

Not all nudges were as cost-effective as this (e.g. one nudge only generated 0.05kWh per $1 spent). Clearly, policymakers can focus on the most cost-effective policies and nudges and actively consider any policy with a net benefit.

What about the unintended consequences of nudging?

As with any policy intervention, policymakers should be wary of possible unintended consequences. Here we note two possible unintended consequences arising from environmental nudges.

First, there is a risk that nudge interventions reduce public support for more interventionist policies. One experiment found that introducing a nudge remedy at the same time as a carbon tax reduced the support for a carbon tax, because the nudge produced ‘false hope that problems can be tackled without imposing considerable costs’.25 Therefore, it may be advisable to be honest with consumers about the scale of the challenge and the role of nudge remedies as useful but not sufficient. When evaluating interventions, policymakers may wish to consider how packages of interventions collectively impact consumer behaviour.

Second, nudges can cause fairness and distributional issues. For example, Ghesla et al. (2020) found that defaulting to (more expensive) green energy tariffs in Switzerland was especially effective among lower-income households.26 This was because lower-income households were more likely to display inertia, sticking with the default tariff. The result of this is that the costs of decarbonisation would be disproportionately borne by the lower-income households, which might not be considered to result in a fair outcome. Such outcomes could also undermine public support in decarbonisation policies. There may be more interventionist policies (or better-designed nudges) that do not result in this type of distributional issue.

Nudge or shove?

In summary, nudges can change consumer behaviour towards decarbonisation—for example, by reducing household energy consumption by 2%.27 Default nudges are likely to be most effective at changing customer behaviour towards the environment.

However, nudges alone are unlikely to produce the step-change required for societies to reach net zero. Like other policies, nudges can also come with unintended consequences, such as distributional issues.

Therefore, meeting the decarbonisation targets set by COP26 is likely to require more than nudging. Nudges alone do not hold the key to reaching net zero.28 In the words of behavioural scientist Ashley Whillans:29

If organizations and policymakers are serious about increasing sustainable behavior, we may need to impose heavier-handed interventions, like fines. In the next 10 years, behavioral scientists need to start throwing every tool they have at climate change—nudges and shoves—alike.

Policymakers will need to reach for the whole range of tools available to ensure that we decarbonise rapidly and fairly.

1 COP26 (2021), ‘The Glasgow Climate Pact’.

2 Oxera (2021), ‘The economics of climate change: a signal in the noise’, Agenda, February.

3 Oxera (2021), ‘Working from home: shove or nudge?’, Agenda, April.

4 See, for example, regarding food consumption and food waste, Reisch, L. A., Sunstein, C.R., Andor, M.A., Doebbe, F.C., Meier, J. and Haddaway, N.R. (2021), ‘Mitigating climate change via food consumption and food waste: A systematic map of behavioral interventions’, Journal of Cleaner Production, 279. See also Bujold, P.M., Williamson, K. and Thulin, E. (2020), ‘The Science of Changing Behavior for Environmental Outcomes: A Literature Review’, Rare Center for Behavior & the Environment and the Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel to the Global Environment Facility.

5 See, for example, Hansen, P.G. and Jespersen, A.M. (2013), ‘Nudge and the Manipulation of Choice: A Framework for the Responsible Use of the Nudge Approach to Behaviour Change in Public Policy’, European Journal of Risk Regulation, 1, pp. 3–28.

6 Oxera (2021), ‘System failure: a problem for behavioural economists?’, Agenda, September.

7 Beshears, J. and Kosowsky, H. (2020), ‘Nudging: Progress to date and future directions’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 161, pp. 3–19.

8 Hummel, D. and Maedche, A. (2019), ‘How Effective Is Nudging? A Quantitative Review on the Effect Sizes and Limits of Empirical Nudging Studies’, Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics.

9 Luo, Y., Soman, D. and Zhao, J. (2021), ‘A meta-analytic cognitive framework of nudge and sludge’, PsyArXiv

10 Mertens, S., Herberz, M., Hahnel, U.J.J. and Brosch, T. (2022), ‘The effectiveness of nudging: A meta-analysis of choice architecture interventions across behavioral domains’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, January, 119:1.

11 Jachimowicz, J., Duncan, S., Weber, E. and Johnson, E. (2019), ‘When and why defaults influence decisions: A meta-analysis of default effects’, Behavioural Public Policy, 3:2, pp. 159–86.

12 Mertens, S., Herberz, M., Hahnel, U.J.J. and Brosch, T. (2022), ‘The effectiveness of nudging: A meta-analysis of choice architecture interventions across behavioral domains’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, January, 119:1, Figure 5.

13 Sunstein, C.R. and Reisch, L.A. (2013), ‘Automatically Green: Behavioral Economics and Environmental Protection’, Harvard Environmental Law Review, 38:1.

14 Mills, S. (2020), ‘Personalized nudging’, Behavioural Public Policy, pp. 1–10.

15 See, for example, Osman, M., McLachlan, S., Fenton, N., Neil, M., Löfstedt, R. and Meder, B. (2020), ‘Learning from Behavioural Changes That Fail’, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, and Sunstein, C. (2017), ‘Nudges that fail’, Behavioural Public Policy, 1:1, pp. 4–25.

16 This is also known as ‘Cialdini’s Big Mistake’. See Cialdini, R. (2003), ‘Crafting Normative Messages to Protect the Environment’, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12:4.

17 Adams, P., Guttman-Kenney, B., Hayes, L., Hunt, S., Laibson, D. and Stewart, N. (2018), ‘The semblance of success in nudging consumers to pay down credit card debt’, Financial Conduct Authority Occasional Paper 45.

18 Bujold, P.M., Williamson, K. and Thulin, E. (2020), ‘The Science of Changing Behavior for Environmental Outcomes: A Literature Review’, Rare Center for Behavior & the Environment and the Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel to the Global Environment Facility.

19 Allcott, H. (2011), ‘Social Norms and Energy Consumption’, Journal of Public Economics, 95:9–10, pp. 1082–95.

20 Allcott, H. and Rogers, T. (2014), ‘The Short-Run and Long-Run Effects of Behavioral Interventions: Experimental Evidence from Energy Conservation’, American Economic Review, 104:10, pp. 3003–37.

21 Schubert, C. (2016), ‘Green nudges: Do they work? Are they ethical?’, MAGKS Joint Discussion Paper Series in Economics, No. 09-2016, Philipps-University Marburg, School of Business and Economics, Marburg.

22 Asensio, O.I. and Delmas, M.A. (2016), ‘The dynamics of behavior change: Evidence from energy conservation’, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 126:A, pp. 196–212.

23 Nisa, C.F., Bélanger, J.J., Schumpe, B.M. and Faller, D.G. (2019), ‘Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials testing behavioural interventions to promote household action on climate change’, Nature Communications, 10:4545.

24 Benartzi, S., Beshears, J., Milkman, K.L., Sunstein, C.R., Thaler, R.H., Shankar, M., Tucker-Ray, W., Congdon, W.J. and Galing, S. (2017), ‘Should Governments Invest More in Nudging?’, Psychological Science, 28:1, pp. 1041–55.

25 Hagmann, D., Ho, E. and Loewenstein, G. (2019), ‘Nudging out support for a carbon tax’, Nature Climate Change. 9:6.

26 Ghesla, C., Grieder, M. and Schubert, R. (2020), ‘Nudging the Poor and the Rich – A Field Study on the Distributional Effects of Green Electricity Defaults’, Energy Economics, 86:9–10.

27 Allcott, H. (2011), ‘Social Norms and Energy Consumption’, Journal of Public Economics, 95:9–10, pp. 1082–95.

28 Schubert, C. (2016), ‘Green nudges: Do they work? Are they ethical?’, MAGKS Joint Discussion Paper Series in Economics, No. 09-2016, Philipps-University Marburg, School of Business and Economics, Marburg.

29 As quoted in Nesterak, E. (2020), ‘Imagining the Next decade of Behavioral Science’, Behavioural Scientist.

Related

Ofgem’s RIIO-3 Sector Specific Methodology Decision

On 18 July 2024, Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Decision (SSMD) for the forthcoming RIIO-3 price control period for electricity transmission (ET), gas transmission (GT) and gas distribution (GD) networks.1 This follows Ofgem’s consultation on the matter in December 2023.2 RIIO-3 will last for… Read More

The future funding of the England & Wales water sector: Ofwat’s draft determinations

On Thursday 11 July, Ofwat (the England and Wales water regulator) published its much anticipated Draft Determinations (DDs). As part of the PR24 price review, this sets out its provisional assessment of allowed revenues and performance targets for AMP8 (2025–30)—and will be of great interest to water companies, investors,… Read More