The benefits of sharing, or sharing the benefits? Cartels and efficiencies in Hong Kong

Is a market-sharing agreement always an infringement of competition law, or could it be justified on the basis that it generates efficiencies? What analysis and evidence is required to answer this question? These were the questions facing the Hong Kong Competition Tribunal in only the second enforcement action brought before it. We look at the economic analysis that was instrumental in helping the Tribunal to decide the case.

Dr Helen Jenkins, Oxera’s Managing Partner, was the expert for the Hong Kong Competition Commission in this case.

In one of its first major rulings, Hong Kong’s Competition Tribunal ruled in favour of the Hong Kong Competition Commission in an enforcement action against ten decoration contractors (‘the Contractors’).1 The Contractors were found to have engaged in market-sharing and price-fixing in relation to the provision of renovation and decoration services at On Tat Estate Phase 1 (‘the Estate’), a public rental housing estate in Kowloon, Hong Kong. The box below provides relevant background.

The Hong Kong Housing Authority’s Decoration Contractor System

In Hong Kong, newly built public rental housing estates are in a ‘bare shell’ condition, meaning that each flat will typically require works (such as floor tiling) before a tenant can move in. The ten Contractors had been granted licences by the Hong Kong Housing Authority to act as Appointed Decoration Contractors (‘Appointed DCs’) on the Estate. The Appointed DCs were allowed to set up an office and market their services to prospective tenants on site, had been vetted to ensure that they were not involved in criminal activities, and were required to provide quality assurances to tenants (including a warranty).

While competition from unlicensed contractors (‘outside contractors’) was also possible, they were not permitted to market their services on site, and the factual evidence indicated that tenants valued the quality and safety assurances brought about by hiring an Appointed DC.

The case concerned allegations by the Commission that, rather than competing for the business of tenants, the Contractors entered into a Floor Allocation Agreement (FAA), whereby they allocated among themselves designated floors in each of the three buildings in the Estate. The Commission’s case was that the Contractors infringed competition law by agreeing not to actively seek business from tenants on floors allocated to the other Contractors and, if approached by those tenants, declining the business and directing the tenant to their allocated Contractor.

The First Conduct Rule of the Hong Kong Competition Ordinance prohibits agreements that have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction, or distortion of competition in Hong Kong. However, agreements can be exempt from the First Conduct Rule if they are shown to enhance overall economic efficiency. The Contractors sought to benefit from this exemption, claiming that the FAA was essential for delivering substantial efficiencies that were in turn passed on to tenants. The main plank of the Contractors’ efficiency defence was that the FAA enabled them to concentrate work at any one time on flats located on the same floor. Significant efficiencies allegedly arose from being able to perform work in multiple flats on the same floor, on account of the time it took to move labour, tools, and equipment from one floor to another, especially given the long waiting times for the lifts (which were alleged to be up to two hours).2

The Tribunal found that the FAA contravened the First Conduct Rule by object, and did not accept the Contractors’ efficiency defence. We discuss below two key issues that were central to the economic debate and the Tribunal’s ultimate findings.

- Issue 1: did the FAA generate efficiencies, or would these have been delivered under a competitive outcome?

- Issue 2: assuming that the FAA generated efficiencies, did tenants benefit from it in the form of lower prices?

Not so efficient, relative to the counterfactual

The Contractors’ expert considered that there were substantial efficiency savings associated with the FAA, as compared with the counterfactual absent the agreement.3

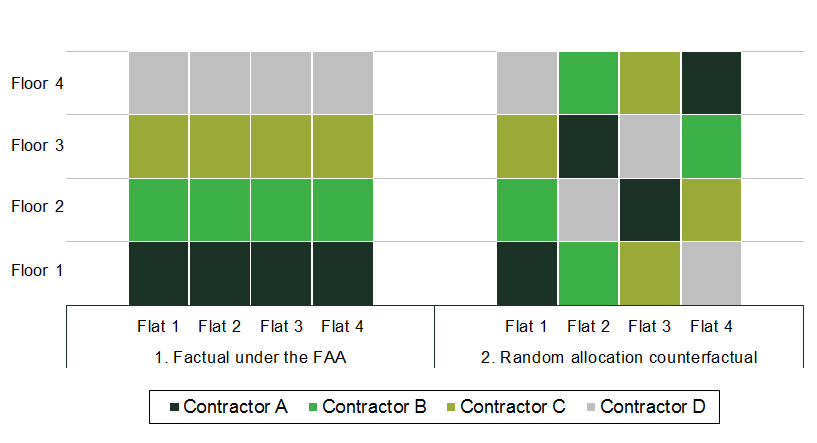

Under the FAA, the Contractors were able to achieve floor-level concentration—i.e. each Contractor was able to concentrate its works on the floors that it was allocated. The Contractors’ expert compared this situation against a counterfactual in which each Contractor won work that was randomly allocated across the floors within the building. In particular, they compared the two scenarios depicted in Figure 1 below. On this basis, the Contractors’ expert concluded that the costs of providing decorative works would be significantly higher under the random allocation counterfactual, as each Contractor would need to use the lifts—and be subject to their long waiting times—more often.

Figure 1 Stylised illustration of distribution of work on the flats

Source: Oxera.

But is this the right counterfactual?

As debated in the trial, from an economics perspective, a random allocation in the competitive counterfactual was unlikely. This is due to two key economic considerations.

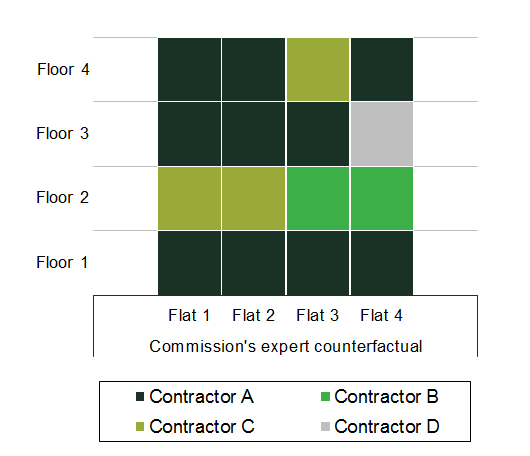

- First, if there are efficiencies of scale or density from decorating several flats on the same floor, the competitive process would be expected to lead to an outcome where these efficiencies are realised in large part. For instance, if Contractor A wins a flat on Floor 1 following a competitive process, it would be expected that Contractor A would offer a lower price for subsequent flats on the same floor, because the cost of completing the second flat for Contractor A is lower given it has won the first flat. Therefore, the counterfactual where Contractors would have been competing is likely to have resulted in some ‘local floor-level concentration’ of suppliers through the competitive process, underpinned by the economies of scale and scope. This is depicted in the counterfactual presented in Figure 2 below, where Contractor A wins four flats on Floor 1.

- Next, given that the Contractors had different costs associated with supplying decorative works, the competitive process would have led to floor-level concentration whereby the more cost-efficient suppliers won more work, bringing about additional benefits as inefficient suppliers would not be sheltered from competition. In Figure 2, Contractor A is assumed to be the most efficient Contractor and is therefore able to achieve floor-level concentration across additional floors.

Figure 2 The distribution of flats under the counterfactual advanced by the Commission’s expert

Source: Oxera.

Ultimately, the Tribunal considered that the random allocation counterfactual was ‘extreme and unjustified’, and was persuaded by the economic arguments put forward by the Commission’s expert that competition would be expected to lead to floor-level concentration that delivers efficiency benefits:4

It follows that if there are indeed efficiencies as alleged from concentrating work on a given floor, then the competitive process is likely to lead to substantial floor-level concentration. In that but-for world the more efficient suppliers might win work on more floors, […]. It may readily be accepted that the “pattern” would not be as neat and regular as under the Floor Allocation Agreement, and each respondent might have some “stray” flats, but it would plainly be a far cry from the assumed scenario where each respondent would be working on 24 to 28 flats spread randomly across 24 to 28 floors in each of the 3 buildings.

On the basis of the above, the Tribunal found that the efficiency savings advanced by the Contractors’ expert were unreliable, as these had been calculated by reference to an ‘unrealistic’ counterfactual.5

The price isn’t right

The second issue in front of the Tribunal was about the impact on tenants. When the case was heard, the Tribunal had yet to rule on whether the FAA had generated efficiencies. As a result, in providing their opinions on whether tenants had benefited from the FAA, the economic experts proceeded on the assumption that the FAA had, in fact, generated efficiencies that would not have been delivered under a competitive counterfactual.

This test involved a balancing (or weighing up) of the alleged procompetitive effects of the FAA against its alleged anticompetitive effects. On the one hand, the FAA was alleged to deliver substantial efficiency benefits that were passed on to tenants in the form of lower prices. On the other hand, the elimination of rivalry among the Contractors clearly altered the level of competition, and had the potential to result in higher prices. Depending on which of these effects dominated, tenants would either have benefited from or been harmed by the FAA.

The Contractors’ expert argued that the claimed cost savings achieved under the FAA enabled the Contractors to offer lower prices to tenants. This argument rested on the claim that there were hundreds of outside contractors competing for the business of tenants on the Estate, and each tenant was at liberty to select an outside contractor rather than one of the ten Contractors. It was also observed that the Contractors collectively won work on 867 out of a total of 2,582 flats on the Estate—i.e. their combined market share was approximately 34%.6

According to the Contractors’ expert, this was evidence that the Contractors were effectively constrained by outside contractors and did not individually or collectively possess market power on the Estate. The expert argued that because of this lack of market power, the elimination of rivalry among the Contractors could not have resulted in higher prices. Rather, the purported intense competition between the Contractors and outside contractors ensured that the Contractors passed on the efficiency savings in the form of lower prices.

The Commission’s expert considered this view to be too narrow, for two reasons.

The Contractors had differentiating attributes that made them more attractive to tenants

The factual evidence indicated that some tenants valued the quality and safety assurances brought about by the licensing process (see the box above). For those tenants with a preference for hiring a Contractor (due to the Contractors’ differentiating attributes as Appointed DCs on the Estate), the elimination of competition among the Contractors effectively enabled each Contractor to exercise significant market power over these tenants on their respective allocated floors. Each of these tenants faced a significant reduction in choice of supplier as a result of the FAA. Even if one were to assume that the FAA did deliver efficiency benefits that were not achievable under a competitive counterfactual, economic theory would still predict that these tenants would not be expected to benefit because the price they paid would be higher. This is because a supplier with market power will have a weak incentive to pass on all the efficiency savings to consumers.7 Conversely, this supplier will have a strong incentive to charge prices above cost, given the lack of competitive pressure under the FAA. These general predictions from economics theory are especially relevant in light of the Tribunal’s finding that the Contractors had the ability to price-discriminate against this group of captive tenants.8

Outside contractors imposed relatively weak constraints

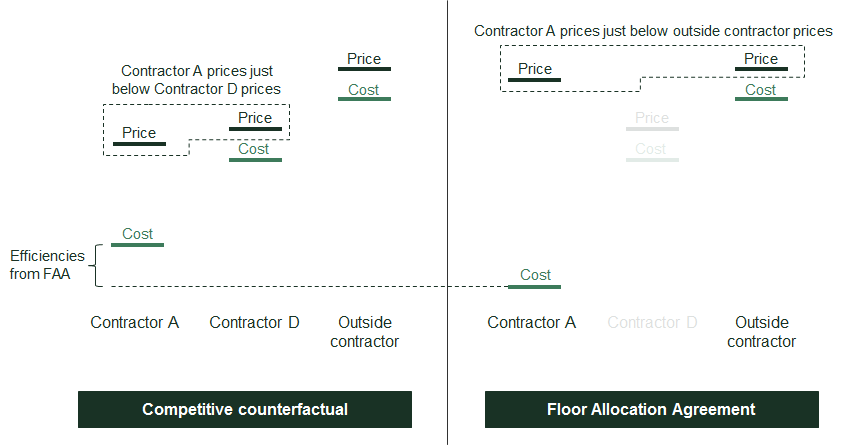

Even in the case of tenants who would consider using an outside contractor instead of an Appointed DC, economic theory predicts that pass-on rates are likely to be low when changes in input costs affect only a subset of suppliers. The evidence indicated that outside contractors would be expected to have higher costs than the Contractors for an equivalent service, even absent the FAA. This, coupled with the fact that outside contractors do not also benefit from the cost efficiencies associated with the FAA (as they are not party to it), implies that the Contractors would have had limited incentives to pass on the alleged efficiencies.

This is depicted in Figure 3 below, which presents a stylised illustration of the competitive dynamics on a floor allocated to Contractor A under the FAA. Under the competitive counterfactual, Contractor A (a relatively efficient Contractor) has an incentive to undercut Contractor D’s price in order to win business. Under the FAA, the constraint imposed by Contractor D is removed, and Contractor A now has an incentive to undercut the outside contractor’s price, which remains unchanged given that its costs are unchanged. This is expected even under the assumption that Contractor A’s costs have fallen, as shown in the figure, due to the alleged efficiencies generated by the FAA. This simple analytical framework predicts that Contractor A’s price will increase under the FAA, and that it will retain the efficiency savings in the form of additional profit, despite being in competition with an outside contractor.9

Figure 3 Contractor A’s pricing incentives on a given floor allocated to it under the FAA

Source: Oxera.

On the evidence, the Tribunal dismissed the Contractors’ argument that the tenants on the Estate received a fair share, or indeed any share, of the efficiencies claimed:

The elimination of rivalry from their closest competitors conferred upon the respondents the incentive and ability to raise prices. The tenants were effectively deprived of any choice between Appointed DCs because only one of them would be prepared to take on work on any particular floor. It is of particular importance in a case such as the present to balance the effect of the restriction on competition and the claimed benefits passed on to consumers. But the same deficiency in the respondents’ analysis of the negative effects of the restrictions flowing from the impugned agreements is reflected in their failure to assess whether the cost savings said to have been passed on to the tenants are sufficient to compensate for the anti-competitive disadvantages.10

Conclusion

The Hong Kong Tribunal’s judgment sets a high burden of proof for firms seeking to benefit from an efficiency defence, requiring them to demonstrate that the agreement in question was essential to deliver the claimed efficiencies, and that consumers received a fair share of any resulting benefit.

However, the Tribunal also set a high burden for the Commission, ruling that, in cases brought before it, the Commission bears the burden of proving a contravention of the Competition Ordinance beyond reasonable doubt (i.e. a criminal standard of proof). This raises important questions as to whether economic evidence can meet this burden of proof in such cases. Nevertheless, the judgment in this particular case demonstrates the value, relevance, and potentially decisive effect of economic evidence.

1 Judgment of Hon G Lam J in the matter between Competition Commission and W. Hing Construction Company Limited and nine others, CTEA 2/2017, 17 May 2019 (‘the Judgment’).

2 The factual basis for this claim was challenged during the hearing, and the Tribunal ultimately found that the claimed efficiencies of scale or density from decorating flats on the same floor together were exaggerated. This was a further reason, in addition to those discussed in this article, why the efficiency defence was rejected.

3 The term ‘counterfactual’ refers to a hypothetical scenario in which the Contractors had not entered into the FAA.

4 Judgment, para. 246.

5 Judgment, paras 247 and 261.

6 Judgment, paras 126–127.

7 Firms facing little to no competitive pressures in the market are not pressured to pass on cost decreases in order to outcompete rivals. The theoretical pass-on rate for a monopolist facing linear, downward-sloping demand is 50%.

8 Judgment, para. 267.

9 This finding is dependent on the relative costs of the Contractors vis-à-vis outside contractors, under the competitive counterfactual. However, the Tribunal agreed with the Commission’s expert’s argument that the efficiency savings would have been passed on only under a set of very stringent conditions regarding the costs of outside contractors, which were unlikely to have held in practice. See Judgment, para. 266.

10 Judgment, paras 270–271. In this extract, ‘Appointed DCs’ is a reference to the Contractors, which were the Appointed DCs on the Estate.

Download

Related

Time to get real about hydrogen (and the regulatory tools to do so)

It’s ‘time for a reality check’ on the realistic prospects of progress towards the EU’s ambitious hydrogen goals, according to the European Court of Auditors’ (ECA) evaluation of the EU’s renewable hydrogen strategy.1 The same message is echoed in some recent assessments within member states, for example by… Read More

Financing the green transition: can private capital bridge the gap?

The green transition isn’t just about switching from fossil fuels to renewable or zero-carbon sources—it also requires smarter, more efficient use of energy. By harnessing technology, improving energy efficiency, and generating power closer to where it’s consumed, we can cut both costs and carbon emissions. In this episode of Top… Read More