Consumer data in online markets

Businesses increasingly use consumer data to offer better and more targeted digital products and services. Many of these new business models rely on data to facilitate transactions and generate revenues in a way that was not previously possible. Access to personal data has understandably raised concerns about privacy. Based on a study commissioned by Which?, we investigate the delicate balance between privacy and the value of digital services.

See Oxera (2018), ‘Consumer data in online markets’, prepared for Which?, 5 June. The Oxera report was part of a Which? project on the collection and use of consumer data—see Which? (2018), ‘Control, Alt or Delete? The Future of Consumer Data’, policy report, June.

We all like finding a discount code for a retailer we’ve been looking at, or finding a hidden café in a city we’re visiting. However, most of us also dislike the idea of our personal information being used in ways we don’t know about or sold to third parties. The Cambridge Analytica case in early 2018 brought to the public’s attention the scale of the data collected about our everyday lives and how it can be misused.1

An increasing number of businesses rely on data to add value by matching consumers and suppliers or generating revenues through targeted advertising. This combination of data and technology has enabled innovation in services that are free of charge, such as video-sharing sites, streaming music and journalism, as well as providing increased choice and lower prices for consumers.

At the same time, the use of this very same data has created competition and privacy concerns. A high concentration of data residing with a few firms could represent a barrier to entry, limiting competition. Meanwhile, consumers do not always know or understand where or how their data is being collected or used, and firms might fail to provide consumers with adequate transparency and control over this.

EU policymakers are acting to improve privacy outcomes, with the introduction of the EU General Data Protection Regulation, which came into force on 25 May 2018, and changes to the Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations on the horizon.2

Consumer data and online services

The impact of consumer data on existing services

Many economic transactions involve significant costs of searching and matching. In the past, consumers booking a holiday might have walked up and down the high street from one travel agent to the next looking for the best deal. Now they can quickly compare deals through one comparison website, such as Expedia or Skyscanner.3

Access to consumer data has made it easier to ‘match’ consumers with products or services—indeed, most online platforms and services rely on consumer data in their matching processes.4 With location data, Uber can identify taxis that are closest to consumers; credit score data enables peer-to-peer (P2P) lenders such as Zopa to match lenders with borrowers; and data about spare rooms allows Airbnb to match hosts with guests.5 Airbnb’s market share of the short-stay accommodation market in London (by number of overnight stays) was estimated to have more than doubled from 2015 to 2016 (from 4% to 9%).6

Better matching also brings direct benefits to consumers because it reduces the time people spend searching for their ‘match’. For example, by entering their preferences into a dating app, those seeking romance can spend less time finding their ideal partner than they would through more traditional methods. According to an online survey in 2016, 29% of men and 22% of women in the UK aged 18–64 use online dating sites or apps.7 In 2017, there were 85.5m active paying online dating accounts across Europe.8

Better matching reduces the costs for new firms to build their customer base. For example, price comparison websites help new firms in a market to acquire consumers quickly (and at lower cost than in the past).

The rise of ad-funded business models that provide better matching of adverts to consumers, such as Facebook, is also partly the result of greater access to consumer data.9 These platforms provide their services free of charge to consumers, but generate their revenues from advertisers (on the other side of the market).

The impact of consumer data on new services

Access to consumer data also has an impact on new services. Many types of digital service rely on the service provider concerned interacting with consumers on a one-to-one basis, in order to find out more about the consumer (i.e. to access data about them). For example, personal trainers meet in person with consumers to assess their levels of fitness and design suitable exercise programmes. With access to consumer data, new service providers can provide services remotely to many consumers simultaneously (and at lower cost). For example, fitness apps and activity tracking devices (‘wearables’) allow consumers to track their fitness and set suitable goals without necessarily requiring a personal trainer, all because the app/wearable provider has access to their personal data.10 According to a 2016 survey, 21% of men and 18% of women in the UK aged 16+ monitor their health or fitness via apps or wearables.11

Economic characteristics of data

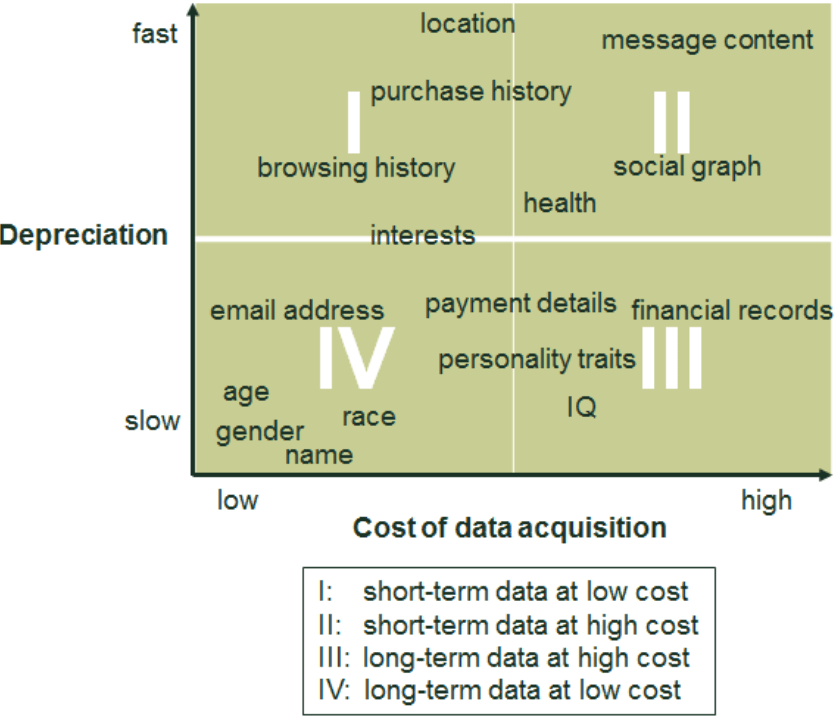

Use of consumer data can affect consumer outcomes in terms of competition and privacy, depending on the economic characteristics of that data. The extent to which different firms are able to access similar data is important for competition, and depends on two key factors.12

- The cost of acquiring data, which in turn depends on how the data is collected. Broadly, this can happen in three ways (from lowest to highest cost): first, people may actively choose to provide their data (e.g. payment details); second, the data is observed from their behaviour (e.g. browsing history); or third, the data is inferred through analysis of previously acquired data (e.g. personality traits). However, people may consider some of their data to be more sensitive than others (such as their bank payment details), and will be less willing to disclose this sensitive data.

- The length of time for which a piece of data remains relevant. The period over which data remains relevant, or when it may need to be ‘refreshed’, is driven by the frequency with which data points may change. For example, someone’s browsing history may represent a useful data point for only a few minutes to several days, whereas their date of birth is relevant for their entire life.13

Figure 1 shows where some types of data could lie along these two dimensions. Starting in the bottom-left corner, data on demographics such as age tends to be widely available, as consumers can provide it multiple times and tend do so without much hesitation. Age also evolves in a fully predictable way, and therefore knowing a person’s age once is sufficient for future reference. In contrast, browsing history is also being tracked by multiple firms at the same time, but it changes constantly and needs to be frequently updated to have any value.14

Figure 1 Characteristics of types of consumer data

Source: Oxera.

Someone’s social network and interactions (their ‘social graph’) is more likely to be accessible to only a few firms, as it is relatively costly to collect and requires regular updating. Complex inferred data, such as personality traits, may be available (in different forms) to various firms at different costs, as this information can be inferred from a range of factors. For example, online browsing behaviour and even bank transaction data can reveal certain personality traits such as conscientiousness or extroversion.15

Firms with access to more comprehensive datasets are likely to have more accurate data—for example, computer models based only on Facebook ‘likes’ are reported to be more accurate at judging personality traits than friends and family.16 The importance of the marginal impact of enhanced accuracy is likely to depend on the specific way it is used.

Competition and consumer impact

The use of consumer data can affect competition. For example, concerns have been raised that a high concentration of data residing with a few firms could represent a barrier to entry.17

Consumers enjoy greater choice through firms competing for customers by innovating and lowering prices. However, choice can also come from competition on non-price factors, such as privacy.

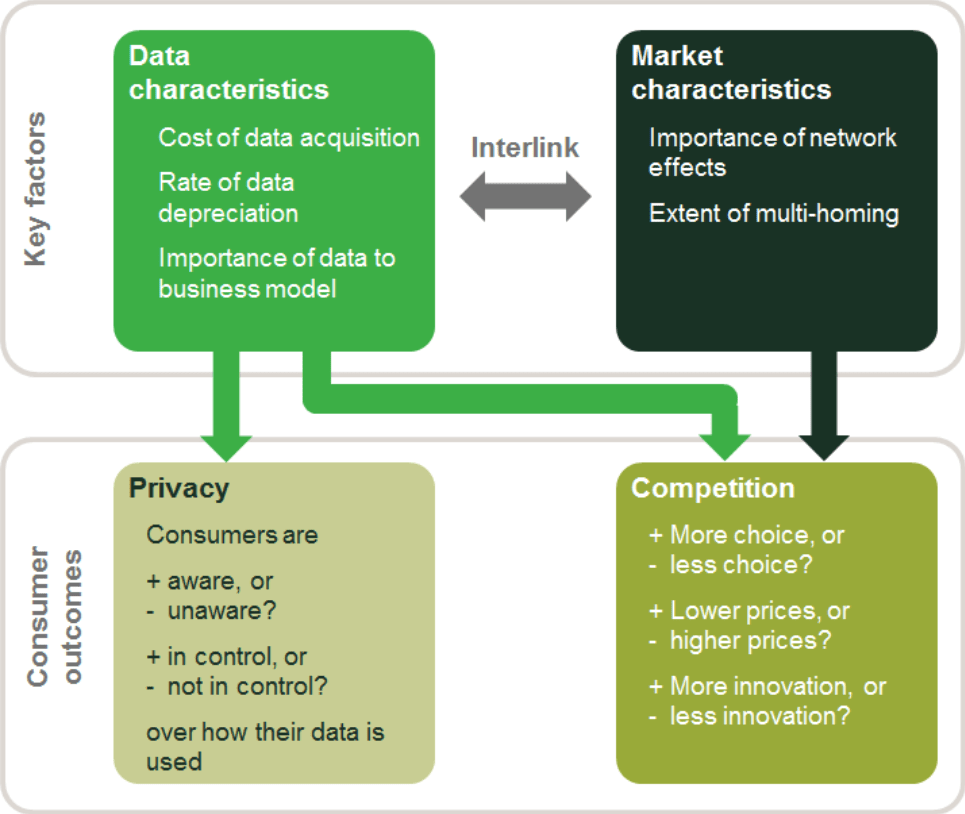

The impact of consumer data on competition is driven by the characteristics of the data itself and the importance of the data for the business model in question. Data that is cheap to obtain and that does not erode quickly in value is likely to be easily acquired by many firms, suggesting that they can compete effectively; while data that does not erode quickly in value, but is costly to obtain, may enable a longer-term advantage in a specific data segment. These characteristics of specific pieces of data interact with the characteristics of the market, such as network effects and multi-homing.18 For example, a lower cost of data acquisition is likely to be associated with more multi-homing.

Figure 2 describes the effect of the use of data and market characteristics on outcomes for consumers, in terms of competition and privacy.

Figure 2 Framework for assessing the impact of consumer data on consumer outcomes

The impact of the use of consumer data on consumer outcomes is broader than competition concerns, as competition alone may not deliver good privacy outcomes. Privacy concerns typically centre on two ‘market failures’:

- consumers may not know that their data is being collected or how it is being used. This failure may be addressed through the party that collects the data giving greater transparency;

- consumers may be unable to prevent their data being used or shared in ways they dislike. Conversely, giving consumers ‘control’ over how their data is used may undermine existing business models, so any remedy would need to be carefully considered. For example, if consumers did not allow social media platforms to use their data for advertising, the platforms might have to charge consumers a fee for their service or limit their services (as they would raise less revenue from the other side of the market).

Consumers are concerned about privacy.19 However, privacy preferences and consumers’ definitions of privacy vary greatly across individuals and contexts—so pinpointing consumer valuations of privacy is notoriously difficult.20 In addition, people do not always act on their privacy preferences in a rational and consistent way, because of ‘behavioural biases’.21 The variation in preferences might suggest that any policy or regulatory interventions should be aimed at helping consumers select the right services and settings for their preferences (despite their biases).

The tension between competition and privacy in online advertising

Online advertising is often designed to sell a product or service, but it can also be designed to influence opinion or behaviour, such as voting or promoting public safety. The aim of using data for targeting is to make adverts more relevant to individuals, thereby increasing the probability of triggering a consumer action in response (such as a purchase or a change in behaviour).

Consumer outcomes

Consumer outcomes from targeted advertising depend on:

- the level of privacy that consumers experience, in relation to the data collected for targeting;

- the degree of competition in targeted advertising, which affects the price and quality that consumers receive from the end product or service being advertised and the digital services that collect the data.

Addressing privacy and competition in targeted advertising is likely to create tensions: competition can lead to good consumer outcomes, but the act of increasing competition may reduce privacy. There are two dynamics in online markets where this tension is displayed.

Dynamic 1: greater competition between ad platforms can lead to greater privacy (and other positive consumer outcomes)

In some markets, firms compete on the basis of greater privacy itself, which leads to greater privacy. For example, in device markets Apple advertises itself as providing greater privacy than its competitors.22

Advertising platforms of all sizes may offer consumers low levels of privacy in terms of transparency and control.23 However, a dominant position may allow an ad platform to impose privacy terms on consumers that would not be acceptable if there were greater competition.24 In such a case, taking measures to increase competition between platforms could improve the privacy offering available to consumers.

Dynamic 2: some mechanisms to encourage more competition between ad platforms are not conducive to greater privacy

To encourage greater competition in online advertising markets, regulators can use a variety of tools, but some of these may be counterproductive if the objective is greater privacy. For example, regulators could reduce the cost of data acquisition by encouraging (or mandating) greater data sharing between advertisers. However, greater data sharing arguably reduces the level of privacy.

Data sharing also has an ambiguous effect on market dynamics more broadly. When it occurs between advertisers, it is likely to make advertisers better off, and ad platforms often benefit from giving advertisers more information on individuals when targeting them in ad auctions.25 However, more extensive data sharing between ad platforms and advertisers might also raise prices under specific circumstances.26

Policymakers should therefore be mindful that any intervention in advertising markets may produce unintended consequences that could harm privacy.

Implications for consumer choice

Advertisers and ad platforms have an incentive to use consumer data in order to closely match their campaigns to individual consumer interests, thereby driving competition on ad technology. They also have some incentive to ensure that consumers do not perceive these ads as too intrusive. Low levels of transparency and control can lead to less privacy than would be optimal for consumers.

Consumers have some limited tools for making the trade-off between maintaining a high level of privacy and encouraging firms to compete by sharing their data widely. For example, people can opt out of being tracked by data aggregators, or by using privacy-enhancing tools such as specific web browsers. It is unclear whether these tools can help consumers to influence data use in advertising markets more widely—and there is still a role for policymakers in striking a balance between competition and privacy.

A clear understanding of consumer preferences is important to ensure good outcomes from the use of data in advertising. A challenge is the variety in preferences, not only across consumers but also across contexts. One way of achieving this understanding might be by making it easier for consumers to choose their preferred privacy settings. Such choices could be presented in easily interpretable ways, as consumers may find it difficult to engage with complex settings about multiple platforms on multiple devices.

Conclusions

Firms have access to much more data about us than they ever have had. Such access to consumer data has raised concerns, including about privacy. However, it has also led to positive changes in many markets and sectors across the economy. It has provided consumers with new products and services, and made existing products and services better and cheaper.

Many of these business models rely on data to facilitate transactions and to generate revenues through targeted advertising, in a way that was not previously possible. This has enabled innovation and delivered benefits to consumers in the form of greater choice or lower prices.

These innovations have, however, also led to risks to privacy. In certain circumstances, competition in the market can mitigate concerns about privacy, crucially depending on whether consumers are able to understand the privacy implications of using a particular service and can exercise choice.

1 See Information Commissioner’s Office (2018), ‘ICO statement: investigation into data analytics for political purposes’.

2 Regulation (EEA) 2016/769 and The Privacy and Electronic Communications (EC Directive) Regulations 2003.

3 Expedia, website homepage; Skyscanner, website homepage.

4 Oxera (2015), ‘A fair share? The economics of the sharing economy’, Agenda, December.

5 Airbnb (2018), ‘What factors determine how my listing appears in search results?’; Uber (2018), ‘How Uber uses location information (iOS)’; Zopa (2016), ‘Zopa and credit scores’, 11 July.

6 Colliers (2017), ‘Airbnb In London’.

7 Statista (2018), ‘Share of users of dating sites or applications in Europe, by sex’. Original source: TNS Sofres (2016), ‘Rapport d’étude Dating et convivialité’, February, p. 8.

8 Statista (2017), ‘eServices Report 2017’, Statista Digital Market Outlook – Market report, December.

9 Facebook, ‘Choose your audience’.

10 Wired (2018), ‘How to Manage your Privacy on Fitness Apps’, 30 January.

11 Statista (2018), ‘Share of respondents monitoring their health or fitness via applications, fitness band, clip or smartwatch in the United Kingdom (UK) in 2016, by gender’. Original source: GfK (2016), ‘Health and fitness tracking’, September, p. 35. Wearables were defined in the survey as a ‘fitness band, clip or smartwatch’.

12 Data can be categorised in many ways; however, these two dimensions capture many of the aspects discussed elsewhere. For example, the discussion of whether data has properties of a public good (by being non-excludable and non-rivalrous) revolves around the question of whether datasets can be replicated. Ultimately, replicability is one factor affecting the cost of data collection. See, for example, Duch-Brown, N., Martens, B. and Mueller-Langer, F. (2017), ‘The economics of ownership, access and trade in digital data’, European Commission JRC Digital Economy Working Paper 2017-01.

13 See, for example, Kennedy, J. (2017), ‘The Myth of Data Monopoly: Why Antitrust Concerns About Data Are Overblown’, Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, 6 March, p. 7.

14 Bujlow, T., Carela-Español, V., Solé-Pareta, J. and Barlet-Ros, P. (2017), ‘Web Tracking: Mechanisms, implications, and Defenses’, Proceedings of the IEEE, 105:8, 28 July, pp. 1476–1510. Englehardt, S. and Narayanan, A. (2016), ‘Online tracking: A 1-million-site measurement and analysis’, Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, October, pp. 1388–1401.

15 Adeyemi, I.R., Abd Razak, S. and Salleh, M. (2016), ‘Understanding Online Behavior: Exploring the Probability of Online Personality Trait Using Supervised Machine-Learning Approach’, Frontiers in ICT, 3:8, 31 May. See Gin, J. (2017), ‘Commercial Psychographic Personalisation’, DataSine blog post, 15 November.

16 Youyou, W., Kosinski, M. and Stillwell, D. (2015), ‘Computer-based personality judgments are more accurate than those made by humans’, PNAS, 112:4, 12 January, pp. 1036–40. See also the seminal paper by Kosinski et al.: Kosinski, M., Stillwell, D. and Graepel, T. (2013), ‘Private traits and attributes are predictable from digital records of human behavior’, PNAS, 110:15, 12 February, pp. 5802–05.

17 See, for example, Kennedy, J. (2017), ‘The Myth of Data Monopoly: Why Antitrust Concerns About Data Are Overblown’, Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, 6 March, p. 7.

18 A network effect is where the benefit that one consumer receives from a network product is affected by how many other consumers also use it. Network effects are a form of economies of scale driven by the demand characteristics of a product rather than the supply side. See Oxera (2013), ‘Snowball effects: competition in markets with network externalities’, Agenda, December. Multi-homing is where consumers use multiple platforms/websites/apps/providers for the same purpose. Using multiple messaging apps is an example of multi-homing.

19 Which? (2018), ‘Control, Alt or Delete? The Future of Consumer Data’, policy report, June.

20 For an overview, see section 3.8 in Acquisti, A., Taylor, C. and Wagman, L. (2016), ‘The Economics of Privacy’, Journal of Economic Literature, 54:2, pp. 442–492.

21 Oxera (2014), ‘Too much information? The economics of privacy’, Agenda, October.

23 For example, see Kennedy, J. (2017), ‘The Myth of Data Monopoly: Why Antitrust Concerns About Data Are Overblown’, Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, 6 March, pp. 15–16.

24 Bundeskartellamt (2016), ‘Bundeskartellamt initiates proceeding against Facebook on suspicion of having abused its market power by infringing data protection rules’, press release, 2 March.

25 Hummel, P. (2018), ‘Value of Sharing Data’, Google Inc.; Hummel, P. and McAfee, R.P. (2016), ‘When does improved targeting increase revenue?’, ACM Transactions on Economics and Computation (TEAC), 5:1, p. 4.

26 de Cornière, A. and de Nijs, R. (2016), ‘Online advertising and privacy’, The RAND Journal of Economics, 47, pp. 48–72.

Download

Related

Ofgem’s RIIO-3 Sector Specific Methodology Decision

On 18 July 2024, Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Decision (SSMD) for the forthcoming RIIO-3 price control period for electricity transmission (ET), gas transmission (GT) and gas distribution (GD) networks.1 This follows Ofgem’s consultation on the matter in December 2023.2 RIIO-3 will last for… Read More

The future funding of the England & Wales water sector: Ofwat’s draft determinations

On Thursday 11 July, Ofwat (the England and Wales water regulator) published its much anticipated Draft Determinations (DDs). As part of the PR24 price review, this sets out its provisional assessment of allowed revenues and performance targets for AMP8 (2025–30)—and will be of great interest to water companies, investors,… Read More