Water mergers: Ofwat’s updated approach

Across industries, mergers and acquisitions play a key role in shaping business landscapes, enabling companies to evolve, grow and innovate. However, they must first undergo assessment by relevant competition and regulatory authorities to ensure that such structural changes do not distort competition, limit regulatory effectiveness (where appropriate), or produce unintended consequences for consumers and affected markets.

When competition authorities investigate mergers in ‘normal’ markets—e.g. supermarkets, concrete or travel operators—they are interested in the impact on real market competition. In contrast, in monopoly utility sectors, where there is limited competition—such as water or energy networks—the investigation is on how a merger might affect the ability of the sector regulator to regulate these companies relative to the benefits that the merger may offer.1 This is because, while the overarching objective of a merger regime is to protect consumers from the effects of excessive market power, the mechanism by which mergers may affect consumer outcomes differs in regulated monopoly contexts. In these cases, the main concern is not a loss of competition, but the loss of a comparator, which can impair the regulator’s ability to evaluate relative performance and inform price-setting decisions.

Market competition versus comparative competition

In more competitive markets, firms are incentivised to optimise their operations in order to attract and retain customers and earn competitive returns. In contrast, natural monopoly markets exhibit different dynamics. Here, economic regulators play a more active role in shaping market conditions, setting cost allowances, and incentivising companies such that efficiency, fairness and service quality are upheld.

A key tool that many regulators use to support these objectives is comparative assessment. For example, setting efficient cost allowances (and, potentially, service performance targets) can rely on comparisons between companies or regions. A proposed merger between regulated companies may affect a regulator’s ability to undertake such comparisons, either by reducing the number of available comparators or reducing the quality of the comparisons. This could potentially lead to harm for consumers if it reduces the ability of the economic regulator to set robust cost allowances and service targets.

However, mergers can also offer benefits such as scale efficiencies, improved operational efficiency, the opportunity to learn from each other’s best practices, and greater financial capacity to support long-term investment and pursue innovation initiatives. In regulated natural monopoly markets, a merger may also improve the comparability of operators for cost benchmarking purposes, as outlined in the assessment of Iberdrola’s acquisition of North West Electricity Networks.2

The England and Wales water sector has a number of regional monopoly companies. Ofwat, the water industry regulator, compares these companies in order to identify the efficiency frontier and set targets, which in turn has an impact on customer bills.

A special merger regime applies in the sector, which is designed to ensure that Ofwat’s ability to use comparative information is not undermined.3 This is somewhat different to the more general mergers regime, which focuses on potential harm to competition rather than on maintaining the effectiveness of sector-specific regulatory tools such as comparative benchmarking.4

As part of this framework, Ofwat is required to provide an opinion to the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) at Phase I of a merger investigation, based on a published Statement of Methods. This document, which Ofwat prepares and keeps under review, must be applied when providing its opinion. The regulator must set out the criteria to be used for assessing the impact of a merger on its ability to make comparisons and the relative weight to be given to the criteria.5

Ofwat needs to identify any potential harm, assess whether this harm amounts to ‘prejudice’, and identify whether there are counteracting ‘relevant customer benefits’ (RCBs)—such as cost synergies. These RCBs are defined in the Water Industry Act 1991 as benefits to customers that would not be achieved, or would be unlikely to be achieved, without the merger.6

Since 2023, a similar regime has existed in the energy sector in Great Britain.7 It was recently used for the first time in the assessment of Iberdrola’s acquisition of North West Electricity Networks,8 during which Oxera advised Iberdrola throughout the entire investigation process with both Ofgem and the CMA. Potentially, these two sector-specific merger frameworks may also be helpful when assessing mergers in other regulated sectors and jurisdictions.

An evolving regime in water

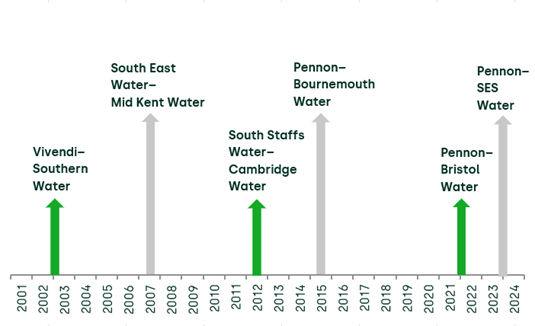

Historically, the water sector in England and Wales has undergone numerous mergers since privatisation in 1989, including those presented in Figure 1 below.

In December 2024, Ofwat opened a public consultation on its proposed revised approach to water mergers and its proposed updated Statement of Methods for the assessment of mergers.9 Building on the previous approach, published back in 2015,10 the revised approach aims to better reflect the evolution of Ofwat’s methodology across multiple price reviews, incorporate changes in the regulatory landscape, and draw on the latest insights from water sector mergers in England and Wales.11

As economic advisers to various water companies in the majority of mergers since 2002, Oxera has examined the impact of these mergers using Ofwat’s Statement of Methods and has contributed to the development of the merger impact assessment approach—as illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 Overview of Oxera’s economic advisory role in water sector mergers since 2002

Building on our extensive experience with water mergers, we responded to Ofwat’s consultation in January 2025.12 Ofwat published its updated approach to water mergers in April the same year.13

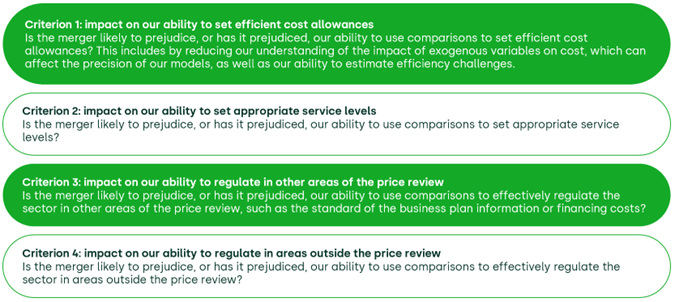

Compared with its 2015 Statement of Methods,14 Ofwat has reduced the number of relevant criteria for assessing the ‘prejudice’ that may occur from a water merger from seven to four. These are outlined in Figure 2 below. Ofwat has also proposed not assigning differential a priori weights to the four criteria, with such assessment to be made on a case-by-case basis.

Figure 2 Updated criteria for assessing the impact of a merger on Ofwat’s ability to make comparisons

Source: Ofwat (2024), ‘Consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, November, para. 4.2; Ofwat (2025), ‘Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, April, para. 4.2; Ofwat (2015), ‘Ofwat’s approach to mergers and statement of methods’, October, pp. 63–66.

Further details and examples of how the assessment of each criterion could be conducted are also provided, with a greater focus on the impact on Ofwat’s ability to set efficient cost allowances (criterion 1). Certain practicalities and proposed tools supporting a more granular assessment—along with the most appropriate approaches and interpretations to adopt in a merger investigation—are discussed below in the context of our response and those of other companies to Ofwat’s consultation document.

In our response, we expressed our support for Ofwat’s refined set of criteria, noting that it offers greater clarity in the assessment process while maintaining a focus on key areas of potential prejudice.

As our main proposal across all criteria, we recommended that the framework consider the proposed RCBs within the prejudice assessment (see Box 1).

Box 1 Oxera’s overarching recommendation

While the framework requires the impact to be modelled before any proposed relevant customer benefits (e.g. cost savings), it is also helpful to model the most likely outcome and thus model the impact after any proposed RCBs (once the merger-specific nature and validity of these have been verified).

Regarding the more detailed approach within Ofwat’s proposed criteria, we provided key recommendations for improving the assessment, focusing on the first two criteria, as these have historically been the primary focus in previous merger impact assessments and are expected to remain so.

As an example of one of our key recommendations regarding criterion 2 specifically—the impact on Ofwat’s ability to set appropriate service levels—we noted that the focus by Ofwat in recent water mergers has been on the impact on setting service performance benchmarks. However, the consultation also mentioned a potential impact on precision in setting service levels—albeit that a more qualitative approach may be undertaken, given the lack of econometric modelling in this area to date. We noted that it was unclear what this analysis would look like, or how useful it would be in gauging the impact of a merger. Our view was that, rather than precision, the main focus should be on the ability of Ofwat to set challenging service performance benchmarks.

Ofwat’s updated approach to mergers and Statement of Methods

While Ofwat has endorsed its initial set of four proposed criteria (see Box 1 above) without any modifications following the consultation period, it has made one key methodological change15 to its initially proposed approach, based partly on our recommendation to consider the proposed RCBs within the prejudice assessment:16

We accept that RCBs, providing they are demonstrably RCBs, may reduce or eliminate some of the harm in theory. Therefore we accept that considering the impact of RCBs may be a helpful additional scenario and we will consider this in our future merger assessments. We have reflected this in the final version of the Statement of Methods. We consider that in practice this is likely to only be relevant to criterion 1.

Such an amendment addresses some of the concerns raised by some companies (Pennon, Wessex Water and Thames Water) that there should be a greater focus on the importance of RCBs within water merger assessments.17

Oxera welcomes this development, which provides greater clarity on the range of relevant scenarios to evaluate. We believe that the direct consideration of the proposed RCBs within the prejudice assessment will enhance the assessment of the merger’s impact on Ofwat’s ability to make comparisons.

Moreover, Ofwat has further clarified how it intends to aggregate its assessment across the four criteria outlined in Figure 2. While it reiterated that no prior weighting will be assigned, it has provided additional clarity on its intended approach—responding to concerns from Thames Water and Affinity Water about the methodology’s application,18 as well as Oxera’s recommendation to assess the merger impact based on the respective size of the various cost areas.19 Ofwat’s stance is as follows:20

In light of the specific circumstances of each water merger, we may consider the scale of the impact on our ability [to] make comparisons, including the certainty around whether the impact will occur. We will consider whether we expect the overall impact, across all criteria, to amount to a prejudice to our ability to make comparisons.

Other amendments to the initial consultation document are limited to providing more context or details on certain points, such as outlining Ofwat’s previous assessment of potential RCBs relative to the small company premium or cost synergies.21

Although our review of Ofwat’s summary of responses to the consultation22 indicates that no other methodological changes have been made to Ofwat’s initially proposed approach from November, Ofwat provides a response to all proposals submitted by Oxera and other stakeholders.23

While we hold differing views with Ofwat on certain aspects of the methodology—such as the degree of informativeness of the general approach,24 or the interpretation of the merger’s impact on Ofwat’s ability to set efficient cost benchmarks—Ofwat has broadly endorsed or confirmed our suggested practical approaches and interpretations on other key points not discussed above. This includes:

- the confirmation that the precision of the cost models in aggregate is an informative metric;25

- that it was unlikely that an analysis of the impact on precision in determining service-level targets would be feasible or useful under the current regulatory framework (albeit with the caveat that the regulatory regime may change in future);26

- uncertainty around how a merger might affect relative (or dynamic) performance measures such as C-MeX or D-MeX (again with the caveat that the regulatory regime may change in future);27

- acknowledgement that, while concerns may arise if a company is a good performer across a range of service-quality metrics, a range of additional factors—such as metric comparability, relative company size, and industry convergence—would also need to be considered to assess the impact of the merger.28

Concluding thoughts

In summary, we consider that Ofwat’s updated approach to mergers offers greater clarity in the assessment process while maintaining a focus on key areas of potential impact.

While providing a solid foundation, the most appropriate approaches in all relevant areas will be merger-specific and will need to be tailored to reflect the specifics of the most recent and upcoming price controls.

This is illustrated, for example, by the form that the forward-looking approach should take when estimating the impact of a merger on the efficiency benchmark level,29 where Ofwat stated that it:30

welcome[s] forward-looking analysis from parties with well-reasoned assumptions and discussion of the accuracy of the model.

1 For more insight into the assessment of mergers, see Oxera (2017), ‘How do you solve a problem like a merger?’, Agenda, December.

2 Competition and Markets Authority (2025), ‘Completed Acquisition by Iberdrola, S.A., through its Subsidiary Scottish Power Energy Networks Holdings Limited, of North West Electricity Networks (Jersey) Limited. Decision on duty to refer’, 20 March, para. 25.

3 The special merger regime is set out in the Water Industry Act 1991.

4 For further detail on the special merger regime in the water sector, see Oxera (2005), ‘Water mergers: what are the prospects?’, Agenda, May; and Oxera (2007), ‘A liquid market for mergers? Assessing acquisitions in the water industry’, Agenda, June.

5 Section 33C Water Industry Act 1991.

6 These would take the form of ‘(i) lower prices, higher quality or greater choice of goods or services in any market in the United Kingdom; or (ii) greater innovation in relation to such goods or services’. See Schedule 4ZA Water Industry Act 1991, para. 7.

7 See Energy Act 2023; and Ofgem (2024), ‘Ofgem’s approach to energy network mergers and statement of methods – Decision’, April.

8 Competition and Markets Authority (2025), ‘Completed Acquisition by Iberdrola, S.A., through its Subsidiary Scottish Power Energy Networks Holdings Limited, of North West Electricity Networks (Jersey) Limited. Decision on duty to refer’, 20 March.

9 Ofwat (2024), ‘Consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, November.

10 Ofwat (2015), ‘Ofwat’s approach to mergers and statement of methods’, October.

11 Ofwat (2024), ‘Consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, November, p. 6.

12 Oxera (2025), ‘Consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods – Oxera response’, 21 January.

13 For Ofwat’s updated approach to mergers and Statement of Methods, see Ofwat (2025), ‘Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, April.

14 Ofwat (2015), ‘Ofwat’s approach to mergers and statement of methods’, October, pp. 63–66. Oxera (2016), ‘Water company mergers: further developments in the pipeline?’, Agenda, January.

15 Ofwat (2025), ‘Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, April, para. 4.8.

16 Ofwat (2025), ‘Summary of responses to the consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, April, pp. 17–18.

17 Pennon (2025), ‘Pennon Group’s response to Consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and statement of methods’, 21 January, p. 1; Wessex Water (2025), ‘Wessex Water’s response to Consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and statement of methods’, January; Thames Water (2025), ‘Thames Water’s response to Consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and statement of methods’, 21 January, p. 2.

18 Ofwat (2025), ‘Summary of responses to the consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, April, p. 8.

19 Ofwat (2025), ‘Summary of responses to the consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, April, p. 10.

20 Ofwat (2025), ‘Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, April, para. 4.3.

21 Ofwat (2025), ‘Summary of responses to the consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, April, p. 6.

22 Ofwat (2025), ‘Summary of responses to the consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, April.

23 For Ofwat’s detailed responses to stakeholders’ feedback, see Ofwat (2025), ‘Summary of responses to the consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, April.

24 The general approach assesses the impact of a merger on model precision relating to the loss of a data point without taking into account the characteristics of the merger parties.

25 Ofwat (2025), ‘Summary of responses to the consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, April, p. 10.

26 Ofwat (2025), ‘Summary of responses to the consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, April, p. 14.

27 C-MeX is a performance commitment designed to improve outcomes for residential customers, while D-MeX is a performance commitment designed to improve outcomes for developer-services customers. Ofwat (2025), ‘Summary of responses to the consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, April, p. 15.

28 Ofwat (2025), ‘Summary of responses to the consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, April, p. 15.

29 The forward-looking approach considers how the merger could affect the benchmarks in future price controls, recognising that companies’ respective cost-efficiencies evolve over time.

30 Ofwat (2025), ‘Summary of responses to the consultation on Ofwat’s approach to mergers and Statement of Methods’, April, p. 14.

Contact

Dr Srini Parthasarathy

PartnerContributors

Related

Related

Decoding the Digital Networks Act: the future of the EU electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework

On 21 January 2026 the European Commission published the long-awaited draft of its Digital Networks Act (DNA)—the proposed new regulation that seeks to ‘modernise, simplify and harmonise EU rules on connectivity networks’.1 As the draft is now being reviewed by the European Parliament and the Council, representing the… Read More

Oxera AI Policy Map – January 2026

For this third edition of the AI Policy Map,1 we have updated our database that tracks key national and supranational AI policy developments across the European Economic Area (EEA) and the UK. This curated collection brings together legal texts, strategy documents and other influential publications relevant to the… Read More