The role of regulation in spurring innovation and growth in the EU and the UK

Since the 2008 financial crisis, both the EU and the UK have experienced sustained periods of low growth and weak productivity. The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated these trends, and their share of global GDP has continued to decline, especially relative to the US and emerging economies. This has provoked scrutiny of the regulatory environment, and raised questions as to whether the current approach to regulation remains suitable. This article follows on from an earlier one on boosting growth and productivity in the EU and the UK,1 with a focus on the specific role of competition authorities.

Introduction

In the EU, the 2024 Draghi report2 highlighted concerns that excessive regulation may stifle growth and innovation. In the UK, the Chair of the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) was replaced, and the UK government has actively encouraged regulators to propose new ways to stimulate growth—namely, by rethinking regulatory approaches, rather than just reducing regulation. However, these efforts come amid competing demands for stronger oversight in sectors such as digital markets, financial services, and utilities.

The expanding mandate of regulators and competition authorities

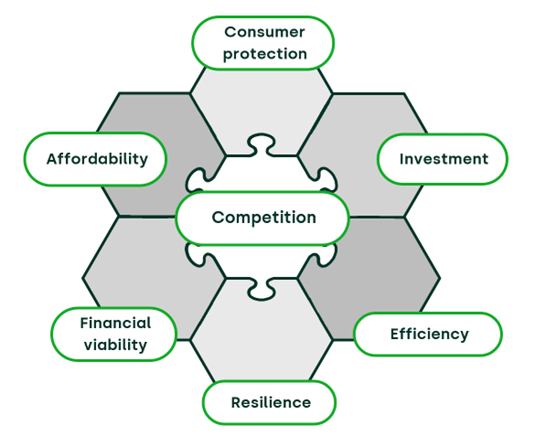

This expansion creates complex trade-offs, as illustrated in Figure 1 below, as objectives such as affordability and long-term investment may conflict. Regulators possess significant discretion in interpreting and balancing these duties, but this discretion also brings risks of regulatory drift and overload.

Figure 1 The merger assessment jigsaw

Competition authorities in the UK and the EU have, traditionally, had three main roles.

- Preventing or amending mergers that could harm competition.

- Enforcing laws against anti-competitive agreements (such as cartels).

- Preventing abuse of market power by dominant firms.

However, in fulfilling these roles, new objectives are being proposed—for example, promoting competitiveness and growth—and there is the risk that the further broadening of mandates may dilute focus and undermine regulatory effectiveness. Additionally, expanding regulatory mandates without concomitant expansion of resources and remit runs the risk of lowering regulatory quality.3

Furthermore, competition policy was, historically, potentially political—with ministers making key decisions—but reforms have granted independence to competition authorities, paralleling the move toward independent monetary policy. However, this depoliticisation may now be questioned, as political pressures mount to refocus regulatory priorities toward growth and industrial policy objectives.4

The UK’s growth duty

The notion that regulators should promote growth is not new. The UK’s Deregulation Act 2015 introduced a ‘growth duty’, requiring regulators to consider the desirability of promoting economic growth. However, the core purpose of competition and financial regulation—namely, to support fair and efficient markets—may already support growth by preventing anti-competitive behaviour and financial instability. Box 1 below discusses the evidence that links growth to the quality of regulation and the efficiency of capital markets. The evidence is mixed, especially with regard to causality; however, there is a clear conclusion that poor regulation and its supporting institutional framework can harm growth.

Box 1 Evidence for the link between competition policy, efficient markets and growth

On a theoretical level, competition policy is the coordination of five tools: antitrust, concentration control, state aid, liberalisation and sector-specific initiatives. The intention is to preserve or intensify competition, so that less efficient actors may exit the market, while the more efficient survivors can offer lower prices and expand the market.

The relation between competition and innovation has also been the subject of academic debate, with Schumpeter suggesting that even monopolists continue to innovate and Arrow proposing that increased competition is a better mechanism; a summary of this debate is provided by Shapiro.5

On the empirical side, a study conducted by the EU6 confirmed this theoretical argument, drawing on evidence from ten case studies. Additionally, a further study7 of OECD countries analysed the impact of competition policy growth for 22 industries in 12 OECD countries over 1995–2005, finding a significant effect and also evidence of a causal link. The link is particularly strong for aspects of competition policy related to its institutional setup and antitrust activities, and is also strengthened by good legal systems.

A related question is the degree of evidence linking capital market efficiency and economic growth. While, generally, a correlation is observed, a conundrum is whether efficient capital markets lead to economic growth, or vice versa, or whether the effects are mutually regenerative. Many studies examining this relation have placed their focus on developing economies (and found mixed results). However, one particular study8 focused on Europe and examined the three hypotheses of efficient financial markets causing growth, or the reverse, or a bidirectional relation. This study concluded that ‘the direction of the relationship between economic growth and financial development depends on the period of study and structure of the groups of countries under study. Therefore, all three hypotheses may be true under the above-mentioned circumstances, which is confirmed by the works of various researchers discussed in the article’. In these ambiguous circumstances, then, the promotion of capital market efficiency is consistent with a ‘growth duty’, even though it does not guarantee economic growth.

There is, however, firm evidence that poor regulation can obstruct growth. For example, one study found that ‘the results based on two different techniques of estimation suggest a strong causal link between regulatory quality and economic performance.’9

Source: Oxera.

There could also be risks in overemphasising economic growth at the expense of other factors, including:

- Distracting from other core duties, such as consumer protection.

- Risk of regulatory capture, where sectoral interests are prioritised over the broader economy.

- Confusion and inefficiency from adding conflicting objectives.

It can be argued that the best way for regulators to support growth is simply to focus on their primary tasks—namely, preventing anti-competitive mergers and abuse, while maintaining market and financial stability.10 Growth should be an outcome of effective regulation, not a competing goal. Of course, poor regulation can be burdensome and hinder growth, which must be avoided.11 In Box 2, we pose the question whether, in practice, the ‘growth duty’ has made any difference at the CMA, and it appears that it has had a discernible effect.

Box 2 Has the growth duty made any difference at the CMA?

According to the latest annual report from the CMA, the answer is a firm ‘Yes’. This question is addressed directly in the CMA’s latest annual report, which refers to ‘embedding a pro-growth mindset across the organisation’12 as one of the things now being done differently.

One initiative is to address organisational effectiveness, through the principles of pace, predictability, proportionality and process. This is intended to strengthen business and investor confidence, minimise uncertainty, and avoid unnecessary burdens. Another is the creation of a new Growth Programme, run by the CMA’s specialist Microeconomics Unit (MU), to support the government’s Industrial Strategy. In a similar vein, a Growth and Investment Council has now been created to bring together the leaders of 12 major UK business and investor groups in service of a common goal: to ensure that effective competition and consumer protection drive innovation, investment, and growth across the UK economy.

But what about decisions on actual mergers? The clearance of the Vodafone/Three merger was cited by the CMA as an example of a growth orientated approach. Following a detailed second-phase investigation, the CMA cleared the merger, subject to legally binding commitments for the merged company to roll out a combined ‘best-in-class’ 5G SA (standalone) network across the UK, requiring an estimated £11bn investment over an eight-year period. To protect consumers, which is paramount for the CMA, during the network rollout, price caps have been placed on selected mobile tariffs for three years, and wholesale prices and contract terms will be regulated. The CMA concluded that these conditions should prevent price rises, saving UK consumers up to £216m a year, while still facilitating the massive investments in new technology.

Source Oxera.

Dealing with the EU’s innovation gap

The Draghi report provides a stark assessment of Europe’s innovation gap. Over the past two decades, European research and development (R&D) investment has been dominated by the automotive sector, while the US has shifted toward technology and biotech, which are areas where Europe is now under-represented. This ‘mid-tech trap’ leaves Europe vulnerable to disruption by new entrants, as seen in the automotive and mobile phone industries.

The lack of a true single market for digital and tech services, combined with regulatory fragmentation, creates barriers for startups and established firms alike. Harmonising regulations and reducing fragmentation would make it easier for firms to achieve scale and compete globally. The Draghi report estimates that €800bn in annual investment is needed for decarbonisation, security, and digital transition; most of this must come from the private sector, but with significant public investment as well. Therefore, the Draghi report argues for a deeper, more integrated single market, especially for digital and tech sectors. Harmonising regulations and reducing fragmentation would enable firms to scale and compete globally.

The implications of the Draghi report for EU regulators go beyond harmonising regulations and reducing regulatory barriers; they also involve ensuring that regulation supports—rather than stifles—new business models and technologies. The report proposes that public investment should be targeted at strategic sectors, such as digital infrastructure, green technologies, and defence (areas where private investment alone may be insufficient). Furthermore, it recommends that the EU should consider new funding mechanisms and incentives to crowd in private capital and support innovation ecosystems—developments that would have obvious implications for State aid rules.

There is also a need to support scale-ups and start-ups and policies should focus on helping innovative firms scale up within the EU. This includes improving access to finance (especially venture capital), simplifying regulatory compliance, and fostering cross-border collaboration. The EU must also attract and retain top talent in tech and science, requiring investment in education, research, and labour mobility.

Short-term vs. long-term focus

For both the EU and the UK, regulation should enable experimentation and the adoption of new technologies, especially in rapidly evolving sectors. Policymakers should also encourage entrepreneurial activity and accept that some failure is inevitable in the pursuit of innovation.

This is linked to a recurring theme: the tension between short-term regulatory goals (e.g. keeping prices low) and long-term needs (e.g. investing in infrastructure, adopting green technologies, etc.). Critics argue that overemphasis on immediate affordability can undermine the investment and innovation required for future growth and resilience. Regulators must strike a careful balance, supporting both affordability and long-term investment. The challenge is to encourage risk-taking and innovation without compromising consumer protection or market stability.

The role of government

A key achievement in recent decades has been the depoliticisation of economic regulation, with independent authorities making evidence-based decisions. However, current political pressures to prioritise growth risk undermining this independence. There is a danger that regulatory decisions could become more politicised, with short-term political considerations outweighing long-term economic benefits. However, in increasingly volatile times, it may also be possible that the political leadership is more aware of changing priorities than the institutional bureaucracy, and lack of agility could also be a liability. In resolving this possible paradox around independence, the effect of independence on quality has been examined,13 and the conclusion was that regulatory independence has a positive effect on quality, which is also improved by increased staffing and more extensive regulatory powers, and the context of a capable bureaucratic system.

Nonetheless, while regulators inevitably have discretion in interpreting their mandates, the balancing of growth, competition, and consumer protection are all matters for government policy. Regulators should implement clear policy frameworks set by elected officials, not resolve inherently political questions. This is especially important as the scope and complexity of regulatory mandates continue to expand.

Priorities for the future

Following on from the review of the UK government’s steer to the CMA and the recommendations of the Draghi report, the following priorities appear to be emerging for competition authorities generally.

- Competitiveness: Europe and the UK must address declining competitiveness, particularly relative to the US and emerging economies. This requires not only regulatory reform but also a renewed focus on innovation, investment, and skills.

- Regulatory reform: There will be pressure to streamline regulation, reduce unnecessary burdens, and focus on outcomes that genuinely support growth. Regulatory frameworks must be coherent, balanced, and adaptable to changing economic realities.

- Digital and green transitions: Regulators will play a crucial role in enabling digital innovation and the transition to net zero. This requires new approaches to risk, investment, and market design, as well as regulatory frameworks that support experimentation and long-term investment.

- Multiple objectives: The challenge will be to maintain effective consumer protection and market stability while fostering innovation and long-term investment. The CMA’s response to its growth duty shows how this may be approached.

These priorities should be supported by rigorous analysis, and progress should be regularly reviewed to ensure that measures remain effective and proportionate in a changing economic landscape. Flexibility and adaptability will be key as new challenges and technologies emerge.

Conclusion

The relationship between regulation, innovation, and growth is complicated. Shifting regulatory focus to growth as a standalone objective could lead to compromises in other directions. Instead, evidence-based regulation should be focused on competition, stability, and consumer protection. The causal link to increased growth and innovation is unclear, according to the research cited above, but the removal of obstructions created by poor or excessive regulation increases the likelihood of these factors occurring.

Policymakers must provide clear direction, ensuring that regulatory frameworks are coherent, balanced, and adaptable to new challenges, while recognising that reducing or changing regulation is not a silver bullet for stimulating economic growth. Effective regulation, which focuses on competition, stability, and consumer protection, should form the foundation for sustainable growth, rather than creating obstacles. Growth can be reliably assured by reducing the negative aspects of regulation and ensuring its quality.

1 Oxera (2025), ‘Boosting growth, competitiveness and productivity in the EU and UK’, Agenda, March. Also relevant are the following podcasts: Oxera (2024), ’Episode 7: The Draghi Report: How to deliver Europe’s innovation imperative?‘, November; and Oxera (2025), ‘Episode 9: How can and should economic regulation contribute to growth?’, January.

2 Draghi, M. (2024), ‘The future of European competitiveness – A competitiveness strategy for Europe’, European Commission.

3 The link between quality and resources and remit was noted in Koop, C. and Hanretty, C. (2018), ‘Political independence, accountability, and the quality of regulatory decision-making’, Comparative Political Studies, 51:1, pp. 38–75.

4 Vickers, J. (2025), ‘Should competition monopolise merger policy?’, International Journal of Industrial Organization, 101.

5 Shapiro, C. (2011), ‘Competition and Innovation: Did Arrow Hit the Bull’s Eye?’, in J. Lerner and S. Stern (eds), The Rate and Direction of Inventive Activity Revisited, University of Chicago Press.

6 European Union (2013), ‘The Contribution of Competition Policy to Growth and the EU 2020 Strategy’, July.

7 Buccirossi, P., Ciari, L., Duso, T., Spagnolo, G. and Vitale, C. (2013), ‘Competition policy and productivity growth: An empirical assessment’, Review of Economics and Statistics, 95:4, pp. 1324–1336.

8 Čižo E., Lavrinenko O. and Ignatjeva S. (2020), ‘Analysis of the relationship between financial development and economic growth in the EU countries’, Insights into Regional Development, 2:3, pp. 645–660.

9 Jalilian, H., Kirkpatrick, C. and Parker, D. (2007), ‘The impact of regulation on economic growth in developing countries: A cross-country analysis’, World Development, 35:1, pp. 87–103.

10 Vickers, J. (2025), ‘Should competition monopolise merger policy?’, International Journal of Industrial Organization, 101.

11 ‘Poor’ could mean overly burdensome in administration requirements (a cost benefit analysis can assist in avoiding this), introducing unnecessary delays, or inconsistent application; all three factors would act as a brake on investment.

12 CMA (2025), ‘Annual Report and Accounts 2024 to 2025’, July, accessed 2 September 2025.

13 Koop, C. and Hanretty, C. (2018), ‘Political independence, accountability, and the quality of regulatory decision-making’, Comparative Political Studies, 51:1, pp. 38–75.

Related

The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say? (Part 2 of 2)

On Thursday 23 October in Brussels, Oxera hosted a roundtable discussion entitled ‘The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say?’. In the second of a two-part series, we share insights from this productive debate. The discussion took place in the context of an… Read More

The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say? (Part 1 of 2)

On Thursday 23 October in Brussels, Oxera hosted a roundtable discussion entitled ‘The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say?’. In the first of a two-part series, we share insights from this productive debate. The discussion took place in the context of an… Read More