The future of merger control: hard Brexit, difficult questions?

The UK’s withdrawal from the EU raises complex issues of policy in many areas of public life. Merger review is no exception, with both EU and UK merger policy being affected. How should the UK’s competition authorities respond to increased demands on their resources in the short-to-medium term? What would be the long-term consequences of applying non-competition considerations in merger review?

Under the EU merger regulation (EUMR),1 proposed mergers between organisations that meet certain turnover thresholds must be reviewed by the European Commission to determine whether they are likely to ‘significantly impede effective competition’ and result in worse outcomes for consumers. Mergers that do not meet the Commission’s thresholds2 may instead be reviewed by national competition authorities, such as the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) in the UK, but the EUMR prevents a merger assessment by both at the same time, thus creating a ‘one-stop shop’ for mergers.

Moreover, when the European Commission assesses a merger, the likely effect on competition is the only factor considered when deciding whether to approve or block the merger, and what remedies to apply. In general, there is little scope for member states to intervene to promote other policies or interests, although Article 21 of the EUMR does allow for intervention in some narrowly defined circumstances (to protect public security, media plurality, or financial stability). If a member state wanted to intervene on the basis of some other public interest consideration, this would need to be notified to, and approved by, the Commission, and tested for compatibility with the functioning of the single market.3

If the UK were to leave the EU but remain in the single market as part of the European Economic Area (EEA) (a ‘soft Brexit’), the UK would remain bound by the EUMR, and the status quo described above would continue. However, if the UK were to leave the EEA (a ‘hard Brexit’), it would be able to review a much wider group of mergers, including those that would otherwise have been reviewed by the European Commission alone. It could also adopt its own policy direction with regard to how those mergers are assessed, which could in principle be quite different to the purely competition-focused approach currently applied by both the European Commission and the CMA.

It is this latter scenario that is the focus of this article. A hard Brexit would raise a variety of complex issues in the field of merger assessment, both legally and politically, with a very real possibility of some radical changes in the way merger control operates in the UK. This has generated much debate, with a leading contribution being the October 2016 issues paper by the Brexit Competition Law Working Group.4 Based on Oxera’s response to this issues paper5 and our other contributions to the debate, we highlight some of the economic questions that would be posed in the event of a hard Brexit, in both the short and the long term.

Potential impact of Brexit on the CMA’s resources and priorities

Immediately following a hard Brexit, the CMA would, all else being equal, have jurisdiction over large mergers that are currently reviewed by the European Commission (this would comprise both large mergers taking place in the UK, and large mergers taking place elsewhere but involving a UK company). This would place additional demands on the CMA’s resources.

One approach to assessing the extent of this additional demand on the CMA is to estimate the proportion of ‘UK-driven’ merger assessment work that is currently conducted by the Commission, and apply this proportion to the reported costs and employees of those elements of the Commission’s responsibilities that will be transferred to the CMA. Using this (admittedly crude) approach, we estimate that UK competition authorities and regulators could require 80–90 additional staff, with an estimated cost of up to £4.8m per year.6 To put this into context, the total direct cost of UK competition enforcement was £66m in 2014–15, with approximately 810 full-time (equivalent) competition staff.7

Assuming there is no increase in funding, it is likely that the CMA would need to reduce its workload in some areas to allow for these extra responsibilities.8 The largest non-mandatory element of its work in this context is enforcement (identifying and remedying violations of competition law, such as price-fixing or abuse of a dominant position), which might be seen by some as low-hanging fruit that could be dispensed with. However, such a reduction in enforcement efforts would go against the National Audit Office’s (NAO) aim, and the CMA’s own ambition, to increase case-flow in the enforcement of competition law.9 Specifically, the NAO has noted that the ‘UK competition authorities issued only £65m of competition enforcement fines between 2012 and 2014 (in 2015 prices), compared to almost £1.4bn of fines imposed by their German counterparts’.10

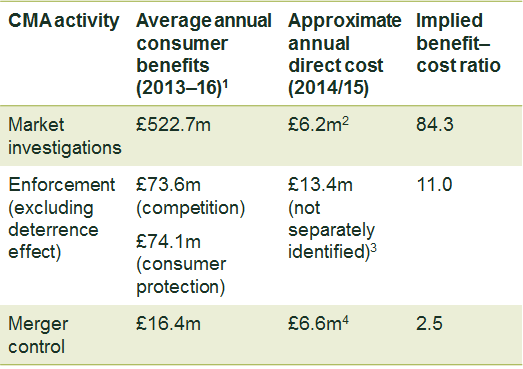

As a result of this tension, economic considerations may drive a refocusing of the CMA’s policy and priorities. The CMA’s own impact assessment of its activities can be informative here, and some high-level findings from this are shown in Table 1. These imply a lower ratio of benefits to costs for merger control than for the CMA’s other main competition functions. While such analysis is inherently uncertain, the scale of difference is quite substantial in this case. From a public policy perspective, activity should typically be concentrated on those areas with the highest benefit–cost ratio.

Table 1 Benefit–cost ratio of CMA activities

While the analysis underlying the CMA’s impact assessment is not publicly available, these results could be taken to indicate that mergers are a possible area where public expenditure could be reduced. There are a number of ways in which this could be achieved.

For example, the CMA currently reviews small as well as large mergers. To reduce the CMA’s workload, one approach would be to introduce a merger threshold below which the CMA is not duty-bound to carry out a review, even when a merger is notified by the merging parties. This would provide the CMA with greater flexibility in its priorities while also ensuring that large mergers are investigated.

Alternatively, the UK could introduce a filter whereby the CMA no longer carries out in-depth reviews of global transactions that are already being reviewed by other major competition authorities—such as the US agencies, the European Commission, and the Chinese authorities. These authorities typically have the greatest influence on a global deal—for example, in terms of enforcing remedies or prohibiting the deal outright where needed. This second option may not always be desirable, particularly where the merger in question still has a large impact on the UK domestic market. However, there may be large global transactions where the impact of a CMA review would be minimal. For example, if the Commission were expected to block a merger, or require significant divestments that also covered the UK, then resources might be saved.

Any such changes to reduce merger review activity would also be likely to have some negative consequences. Reducing the duty to review smaller mergers, or no longer reviewing large-scale global mergers, could result in worse outcomes in ‘small’ domestic markets in the UK. Such consequences should be weighed against the ability of a potentially overstretched CMA to reliably and robustly fulfil its duties.

The economic consequences of applying non-competition considerations in merger approval

In the long term, even more marked policy changes may be possible. If the UK were to leave the EEA, the government would have the opportunity to apply wider considerations of public interest to mergers that are currently analysed by the European Commission on competition grounds alone.

A ‘public interest test’ would not be new to UK competition policy. Indeed, such a test was part of the UK’s Fair Trading Act 1973 (the predecessor to the current Enterprise Act 2002).11 This test stipulated that the competition authority could consider ‘all matters which appear to them in the particular circumstances to be relevant’, including ‘(d) …maintaining and promoting the balanced distribution of industry and employment in the United Kingdom’ when considering mergers. Under this regime, the competition authority made recommendations based on this test, while the ultimate decision-making power remained with the relevant Secretary of State.

A wide range of policy considerations could, in principle, be included in such a test. Government interventions in the interests of public security, media plurality or financial stability are already allowed for in the current competition regime, and these could be strengthened or given higher priority. Broader considerations of factors such as environmental protection, promoting investment in certain sectors or geographies, development of particular technologies, or promotion of employment, could also be considered. In particular, with a key role taken by the newly formed Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS), the UK government has shown an increasing interest in issues of domestic ownership and the distribution of wealth across skills and geographies.12 A long-term policy development whereby these factors could influence whether a merger should be approved is being explicitly considered by a Commons Select Committee.13

Would such a development be desirable? Free-market economics would suggest that there is a case for leaving matters of foreign ownership and geographic location to the market. Government intervention in such decisions, including as part of merger reviews, is therefore likely to result in less economically efficient outcomes. To illustrate this with a theoretical example, if an investor identifies a profitable opportunity to cut costs by acquiring a factory in the UK, shutting down part of its operation and supplying the related parts from a factory located elsewhere in the EU, the merged entity will be able to produce the same amount of goods at an overall lower economic cost. For this reason, in the long term, policies that serve to limit or deter14 mergers between non-UK and UK companies purely on the basis of nationality could be expected to result in lower overall output.15

In addition to these theoretical concerns are a myriad of more practical concerns, which again risk compromising economic efficiency. A public interest test could result in substantial uncertainty for business compared with the current situation of a well-established competition-based regime. Moreover, to the extent that the test is conducted by government, it could be subject to short-term political expediency or populist influences, particularly if defined vaguely. A lack of clarity for business, and subjectivity on the part of political decision-makers, were both criticisms made of the previous ‘public interest test’ under the Fair Trading Act 1973, where on 31 occasions between 1973 and 2001 the UK government acted contrary to the advice of the Director General for Fair Trading on whether to refer a merger.16

There is therefore likely to be a cost from a public interest test in terms of economic efficiency. However, this is not to say that policy should be determined by economic efficiency alone, as a government may take a legitimate interest in a range of other factors. To take an example linked to the UK government’s statements on industrial strategy, it is a matter of policy judgement whether it is preferable to have a more efficient industry that concentrates the distribution of returns, or a less efficient industry or set of industries that distributes returns more evenly.17

The difficulty in merger decisions, however, is that the long-term effects (such as the economic impact on a given group or geography) are difficult to identify—particularly given the strict timetables of merger reviews. Short-term direct effects (such as job losses) will tend to be more directly apparent and quantifiable than longer-term effects that are inherently less certain and diffuse. Without a careful assessment, this creates the risk of a bias towards blocking mergers on distributional or industrial strategy grounds, even when such concerns are unfounded. Equally, there would be a risk of short-term benefits (such as direct investments) being used to support a merger on public interest grounds, even where there are material competition issues that are likely to result in worse consumer outcomes in the long run.

These considerations all suggest that a cautious approach is needed in implementing any broader test for mergers. If policymakers do decide to adopt such a test, economics principles suggest three policy features that would be desirable in order to minimise any negative economic consequences.

First, non-competition-related tests should not be subjective. For a given public interest objective, the associated test of whether to allow or prohibit a merger should be conducted under a prescribed framework, with the authority and/or merging party being required to demonstrate, using that framework, the contribution or harm that a merger poses to that objective. Established ‘impact assessment’ tools for assessing public policy or regulatory interventions may be a useful basis for such frameworks. These tools include guidance on how to quantify, and thus compare, competing public interests that are not inherently monetary, such as distributional and environmental effects, which will help to reduce the element of subjectivity if the test covers multiple objectives.18

Second, the assessment may be best conducted by an independent body. As in the current competition-based regime, there are advantages to removing merger clearance decisions from direct political control. In practice, the CMA itself may not have the expertise needed to assess a merger’s impact on a public interest goal (although its large group of panel members have a range of backgrounds, including public policy). Alternative independent assessors could be involved, such as sector regulators or a specialist panel, depending on the specific case or policy objective considered.19 If such an approach were taken, it is likely that mergers would be reviewed by (and need clearance from) both the CMA and the additional independent assessor, although the CMA could continue its role as overall coordinator of the process.

Inevitably, non-competition considerations would bring additional complexity to the merger control process. For this reason, transparency would be especially important. Whatever the specifics of the process, the same standards of transparency would need to apply as those applied to the current regime. As with many areas of policy, this would help to maintain trust in the process, and allow decisions to be subject to wider scrutiny and challenged where appropriate. It would also allow legal and economic advisers to understand how any public interest test was being applied, and provide advice to private-sector organisations accordingly, helping to reduce any negative effects on business uncertainty.

Life for merger policy after Brexit

At the time of writing, there is a high degree of uncertainty about the terms of the UK’s relationship with the EU after Brexit. This is driving uncertainty about the future of many areas of public policy—and merger control is no exception. There are scenarios in which UK merger policy could continue in line with the status quo for years to come. Equally, there are scenarios in which radical short- and long-run changes are possible.

There are also important policy questions about what happens to EU competition law, which will continue to be of great significance to international businesses, including those based in the UK. Over the years, the UK has had a positive (economically oriented) influence on competition policy in the EU and in other member states. Whatever developments take place in the UK regime, it would seem equally important for UK policymakers and businesses to remain engaged with the pan-European discussions on competition policy after Brexit.

This article is closely based on Oxera (2016), ‘Economic observations concerning competition policy following Brexit’, note prepared for BCLWG, 30 November.

1 Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 of 20 January 2004.

2 All mergers with an ‘EU dimension’ can be examined by the European Commission. This primarily applies where ‘(a) the combined aggregate worldwide turnover of all the undertakings concerned is more than EUR 5000 million; and (b) the aggregate Community-wide turnover of each of at least two of the undertakings concerned is more than EUR 250 million, unless each of the undertakings concerned achieves more than two-thirds of its aggregate Community-wide turnover within one and the same Member State’. Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 of 20 January 2004, Article 1(2).

3 The UK does have more discretion over how to review mergers that fall outside the EU’s jurisdiction, although in practice the current UK public interest intervention rules are similar to those of the EU. The Enterprise Act 2002 contains a broadly similar list of three public interest considerations that can be applied when considering mergers. See Competition and Markets Authority (2014), ‘Mergers: Guidance on the CMA’s jurisdiction and procedure’, January, para. 16.6. This was the basis on which the Lloyds TSB takeover of HBOS was cleared by the UK government in 2008, without reference to the then Competition Commission. Seely, A. (2016), ‘Mergers & takeovers: the public interest test’, House of Commons Library Briefing Paper, Number 05374, 1 September.

4 Brexit Competition Law Working Group (2016), ‘Issues Paper’, October, accessed 25 October 2016.

5 Oxera (2016), ‘Economic observations concerning competition policy following Brexit’, note prepared for BCLWG, 30 November.

6 This is an order of magnitude estimate derived by assuming that the proportion of DG Competition’s work that relates to the UK is in approximate proportion to EU GDP. Staff numbers from European Commission (2014), ‘DG Competition Annual Activity Report 2014. Annexes’, accessed 5 May 2016.

7 National Audit Office (2016), ‘The UK competition regime’, 5 February, para. 8.

8 See also Oxera (2016), ‘Brexit: implications for competition enforcement in the UK’, Agenda, June.

9 Competition and Markets Authority (2016), ‘Annual plan 2016-17’, March, para. 2.3.

10 National Audit Office (2016), ‘The UK competition regime’, 5 February, para. 15.

11 Fair Trading Act 1973, 84.

12 For example, see the speech by the UK Prime Minister, Theresa May, to the CBI on 21 November 2016, accessed 22 November 2016.

13 The Business, Innovation and Skills Committee has launched an inquiry to consider, among other things, ‘what the Government means by industrial strategy and questions how interventionist in the free market it should be, such as whether it should prevent foreign takeover of UK companies’. Commons Select Committee (2016), ‘Committee launches inquiry into Government’s industrial strategy’, 1 August, accessed 23 November 2016.

14 The deterrence effect on foreign investment of a government preference for domestic ownership has some empirical backing. See Serdar Dinc, I. and Erel, I. (2013), ‘Economic nationalism in mergers and acquisitions’, The Journal of Finance, 68:6, pp. 2471–514.

15 A survey of evidence for the Economic and Social Research Council confirms positive effects on overall employment and competitiveness from non-UK takeovers of UK firms. See Economic and Social Research Council (2010), ‘Foreign ownership and consequences for British business’, Evidence Briefing, December.

16 Lyons, B., Reader, D. and Stephan, A. (2016), ‘UK Competition Policy Post-Brexit: In the Public Interest?’, CCP Working Paper 16-12.

17 Economists often abstract from such issues by assuming that a social planner can redistribute income through taxation and benefits if desired. In practice, the government’s ability to shift economic value may be more limited.

18 For example, see OECD (2011), ‘Regulatory Impact Analysis: A Tool for Policy Coherence’, 11 September. UK frameworks include HM Treasury (2013), ‘The Green Book: Appraisal and Evaluation in Central Government’, 18 April; and National Audit Office (2010), ‘Assessing the Impact of Proposed New Policies’, Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General, 28 June.

19 Gerard, D. (2012), ‘Effects-based enforcement of Article 101 TFEU: the “object paradox”’, Kluwer Competition Law Blog, 17 February.

Download

Related

Ofgem’s RIIO-3 Sector Specific Methodology Decision

On 18 July 2024, Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Decision (SSMD) for the forthcoming RIIO-3 price control period for electricity transmission (ET), gas transmission (GT) and gas distribution (GD) networks.1 This follows Ofgem’s consultation on the matter in December 2023.2 RIIO-3 will last for… Read More

The future funding of the England & Wales water sector: Ofwat’s draft determinations

On Thursday 11 July, Ofwat (the England and Wales water regulator) published its much anticipated Draft Determinations (DDs). As part of the PR24 price review, this sets out its provisional assessment of allowed revenues and performance targets for AMP8 (2025–30)—and will be of great interest to water companies, investors,… Read More