Lifting the weight of state aid from project finance

In the EU, support provided by the state to finance projects operating in competitive markets typically needs to comply with state aid rules. However, there may be challenges in structuring project financing from the state in a way that is compliant with these rules. What are the fundamental elements to consider when assessing whether the funding confers an economic advantage on the recipient? What alternative financing structures could be considered?

Project finance refers to the financing of a specific asset in return for the cash flows generated by that asset.1 It is used to fund a variety of infrastructure projects, including energy, transportation and telecoms projects.2

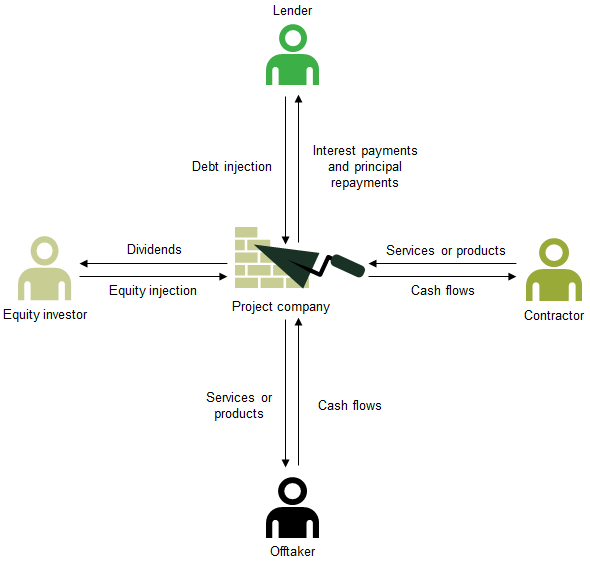

Project finance generally includes a special purpose vehicle,3 or project company, whose sole purpose is to undertake the project. A typical project company may have financial arrangements with a wide variety of counterparties, such as equity investors and lenders. A simplified example of such potential financial arrangements is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 Potential project finance arrangements

Source: Oxera.

If the project company enters into bankruptcy, financiers can rely only on the value of the project’s assets to recoup their investments. For example, if the construction of a real estate project is funded by project finance, the investors can expect to receive only the rental payments from the project, after taking into account the relevant costs.

If the state also provides financing to the project, as either an equity investor or a lender, it is often important to ensure that this is undertaken in a state aid-compliant manner. This article discusses the role of economic and financial tools in assessing whether the state’s intervention in project financing arrangements confers an economic advantage. The article then considers possible financial structures that could be adopted in some circumstances in order to mitigate state aid risk.

Snapshot: the definition of state aid and the market economy operator principle

State aid is defined as an advantage conferred on a selective basis to undertakings (such as the project company) by public authorities that has the potential to distort competition and trade between EU member states.4

Support from the state can take a variety of forms, including direct subsidies, tax exemptions, or loans at below market rates. In order to determine whether such support constitutes aid, among other aspects, it must be assessed whether the support confers an economic advantage on the recipient.5 In order for the support not to confer an economic advantage, it must be shown that economic transactions carried out by the state are in line with normal market conditions. The relevant question is whether, in similar circumstances, a private investor of a comparable size operating in normal conditions of a market economy could have made the investment in question.6 This is referred to as the market economy operator principle (MEOP).

If funding from the state is provided under the same terms and conditions as that from private investors, this implies that the transaction is in line with market conditions.7 However, if the intervention by public bodies is not made under the same circumstances, or there are no private operators involved in the transaction, this does not automatically mean that the transaction does not comply with the MEOP. In such cases, economic and financial analysis is needed to assess whether the transactions are in line with the MEOP.

Understanding the rules of the game: players beware

The MEOP sounds deceptively simple. However, as the saying goes: ‘the devil is in the detail’. As the European Commission has explicitly acknowledged, the process of assessing whether a measure confers an economic advantage may involve very complex economic assessments.8 The next sections explore some of the fundamental elements of robust economic and financial evidence in such circumstances.

Choosing the correct methodology for the MEOP analysis

The MEOP test is typically applied on a forward-looking basis to assess whether an economic transaction involving the state is in line with market conditions (i.e. whether the state’s actions are in line with those of a market economy operator). The following two main approaches are typically used.9

- Ex ante profitability. Based on a sound financial plan, if the state can show that its expected return from providing the funding is as least as high as the return that would be required by a market economy operator, this suggests that there is no economic advantage. It must be shown that this conclusion is expected to hold even in the event that plausible downside shocks were to materialise (such as a reduction in demand). For the purposes of this assessment, only those revenues and costs linked to the state’s role as an economic operator should be taken into account, and not those linked to its role as a public authority (such as tax revenues).10

- Price benchmarking. This approach is based on the idea that similar assets or services should be valued at similar prices. Generally speaking, this approach requires the proposed terms offered by the state to be compared with the market price.11 An economic advantage may not have been conferred if it can be shown that private investors enter into similar transactions on similar terms and conditions.

The Commission’s preferred approach to applying the MEOP test varies by sector. For example, in the broadband sector, in order to determine whether support from the state confers an economic advantage, the assessment focuses on whether business users of broadband can obtain similar prices on the market.12 Similarly, in the seaports sector, the Commission has indicated that the price benchmarking approach is preferred in order to assess whether agreements with operators are in line with the MEOP.13 However, the ex ante profitability approach, rather than price benchmarking, is recommended for determining whether agreements between airports and airlines are in line with the MEOP.14

The choice of methodology in a particular context will depend on many factors, and there may be circumstances where it is appropriate to apply both approaches. The EU’s General Court has concluded that the selection of the appropriate tool is a matter to be decided by the Commission, taking into account the context and specifics of the transactions in question.

In-depth understanding of the assumptions underpinning the MEOP analysis

While the above two approaches establish the starting point for the economic and financial analysis, the details of the application of the method will need to withstand scrutiny from the Commission.

For example, in the context of a state aid investigation into multiple capital injections by the state for Ciudad de la Luz, a film studio in Spain, the state provided several studies, and a business plan, which concluded that the project was expected to generate positive profits.15 However, the Commission questioned several assumptions in the business plan. In particular, according to the Commission, the expected return appeared to be too low—i.e. the Commission queried whether the discount rate used was in line with returns required by private equity investors.16 During the investigation, the Commission, together with an external consultant, revised the discount rate assumption in the business plan.17 As a result, the Commission concluded that the capital injections were not in line with the MEOP.18

Therefore, applying the right methodology, together with an in-depth understanding of the assumptions underpinning the business plan, is paramount to a finding of no economic advantage.

The Commission, supported by the European courts, recommends that robust economic and financial evidence is prepared in advance of interventions by the state in contestable markets (such as financing provided by the state to companies that compete with other companies in the market). In particular, the courts have repeatedly discouraged reliance on retrospective assessments in order to justify state investments.19

In the context of project finance, in addition to a sound business plan a well-designed financing arrangement should be in place, as the state’s returns are directly linked to the form and structure of the financing. Two potentially suitable project financing arrangements are explored below.

Game plan: structuring MEOP-compliant financing

Project financing usually relies on a mixture of debt and equity.20 Therefore, the state could take the role of an equity or debt investor. Typically, in the former scenario, the state would receive returns in the form of dividends or capital gains. In the latter scenario, the state’s return would be determined primarily by the level of interest payments. To be MEOP-compliant, the commercial return expected by the state needs to be in line with returns expected by private equity or debt investors in similar projects. The box below provides further details.

The application of the MEOP test for funding provided by the state in project financings

Generally, in addition to assessing the robustness of the project’s business plan, there are two key components to the MEOP analysis of financing provided by the state. This illustration is based on the state providing a hypothetical loan.

• Benchmarking the terms and conditions of the loan. The level and the timing of interest payments, the level of collateral underpinning the loan, the implied gearing ratio,1 the repayment(s) of the principal, and the duration of the loan need to be shown to be in line with terms that would be provided by a private lender.

• Assessing the serviceability of the loan. As the state’s returns are tied to the project’s assets, in order to be in line with the MEOP, it needs to be shown that the project is expected to be able to generate the required level of cash flows to finance the required payments on the loan at each repayment date.

Note: 1 If a project is particularly risky—for example, if it depends on the use of novel technology—private lenders in similar circumstances might not be willing to provide the entire project financing using debt; however, it is possible that other types of investors would be willing to invest. Therefore, when applying the MEOP test, the financing arrangements for comparable projects should be taken into account.

Source: Oxera.

However, simple debt or equity financing structures may not always provide the required debt or equity returns to the state and the project sponsors (e.g. individuals who carry out the day-to-day operations of the project). For example, there may be certain situations where, in order to compensate the state adequately for its equity injection—i.e. to pass the MEOP test—the project sponsor would expect to sell its shareholdings in the project company to the state. Alternatively, it may not be ideal to service a financing arrangement with a pre-determined, fixed, repayment profile. In such scenarios, more bespoke solutions may be necessary. Two potential project finance arrangements are described below. They assume that the projects have relatively long lives and expect, under robust assumptions, to deliver commercial rates of return overall based on sound business plans.

Balancing the books: refinancing loans

A project might take on a short-term project finance loan that could be replaced (or ‘refinanced’) once the project is in operation and has demonstrated its viability. In theory, if the project is successful, the refinanced loan should contain more favourable terms, such as lower interest payments. Therefore, if the state provides a refinanced loan at lower interest payments than the original loan, this could still be MEOP-compliant. However, an MEOP assessment may be required at the time when the state provides the initial loan as well as the refinancing to ensure that the terms of the loans are in line with the market.

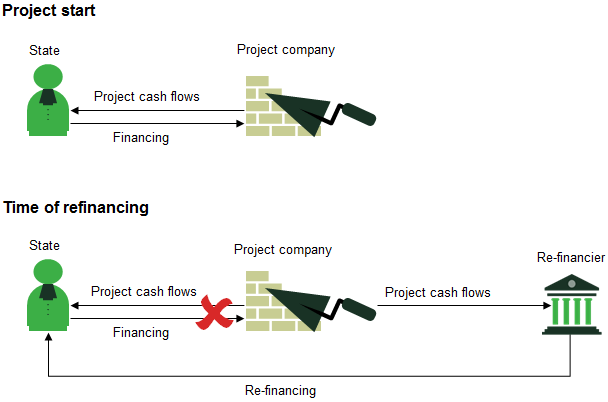

Alternatively, it is possible that, at the time of the refinancing, the project could also attract private investors to refinance the loan. For example, a private debt investor might provide the funding to enable the amount of the loan outstanding to be repaid to the state. In return, the private debt investor would receive remuneration based on the project’s expected future cash flows. In this case, the state aid risks might be reduced at the time of refinancing. Figure 2 shows a simplified illustration of such a refinancing arrangement.

Figure 2 Potential refinancing from a private investor

Source: Oxera.

To crown it all: royalty agreements

Royalty financing represents an alternative structuring option. It is commonly used in a number of markets, particularly in the energy,21 pharmaceutical and oil and gas industries.22 Some investment companies also exclusively focus on royalty financing.23

Typically, a royalty financier provides financing in exchange for a proportion of the project’s future revenues.24 Similarly to an equity investment, if the project proves to be successful, a royalty investor can benefit from the upside. From a project company’s point of view, royalty financing may be more flexible than debt financing, since the repayment schedule—e.g. the level of repayments—is not pre-defined.

Unlike an equity investor, a royalty financier is relatively insulated from variations in costs, provided that the project is not in financial distress.25 For example, a royalty that depends only on revenue may not be suitable for financing a project where the operational costs are expected to grow significantly over the long term. Furthermore, while an equity investor has only a residual claim on the project’s cash flows, a royalty investor may require collateral (security for taking on the risk of the investment).26

While there are advantages of a royalty agreement in terms of state aid compliance, such as the relative ease of incorporating such an agreement into a business plan, as the state’s remuneration is determined solely by the level of expected revenues from the project, there are also downsides. In particular, it can be difficult to benchmark the covenants required in a royalty agreement across different projects, as they are often tailored to the specific circumstances.

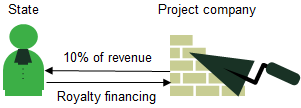

Figure 3 shows a simplified illustration of such royalty financing, where the state provides financing to the project company.

Figure 3 Potential revenue royalty project financing

Source: Oxera.

In a nutshell

In the context of project finance, if the state is providing financing to a project then it may be necessary to assess, using the MEOP test, whether the funding confers an economic advantage.

While the idea behind the MEOP test may sound simple, there are challenges in its application. For example, to be MEOP-compliant, it is often crucial to be able to demonstrate that the state expects to receive a commercial level of return in advance of the transaction(s).

However, simple financing structures may not always provide the required debt or equity returns to the state and the project sponsors. In such scenarios, project sponsors may be able to consider alternative financing structures that will allow them to finance their projects in a state aid-compliant manner while also meeting their financial objectives.

1 Association for Financial Markets in Europe and International Capital Market Association (2015), ‘Guide to infrastructure financing’, June, p. 16.

2 Dentons (2013), ‘A Guide to Project Finance’, p. 1.

3 The company created for a specific objective.

4 European Commission (2019), ‘State aid: State aid control’, 14 February, accessed 15 March 2019.

5 It must also be assessed whether the support is provided through state resources and is imputable to the state, if it is selective, and if it has the potential to distort competition and trade.

6 European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Notice on the notion of State aid as referred to in Article 107(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union’, Official Journal of the European Union, 19 July, para. 74.

7 European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Notice on the notion of State aid as referred to in Article 107(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union’, Official Journal of the European Union, 19 July, para. 86. For example, see European Commission (2007), ‘Commission decision of 11.XII.2007 on the state aid case C 53/2006 (ex N 262/2005, ex CP 127/2004), Investment by the city of Amsterdam in a fibre-to-the home (FttH) network’, Official Journal of the European Union, 16 September.

8 European Commission (2013), ‘State Aid Manual of Procedures’, 10 July, p. 9, accessed 27 March 2019.

9 Other approaches or variations of the two main approaches may be considered, depending on the context and specifics of the assessment.

10 European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Notice on the notion of State aid as referred to in Article 107(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union’, Official Journal of the European Union, 19 July, para. 77.

11 European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Notice on the notion of State aid as referred to in Article 107(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union’, Official Journal of the European Union, 19 July, paras 98–100.

12 European Commission (2017), ‘Infrastructure Analytical Grid for Broadband Network Infrastructure’, 22 November, para. 15.

13 European Commission (2017), ‘Infrastructure Analytical Grid for Port Infrastructure’, 22 November.

14 European Commission (2014), ‘Communication from the Commission – Guidelines on State aid to airports and airlines’, 4 April.

15 European Commission (2012), ‘Commission decision of 8 May 2012 on state aid SA.22668 (C 8/2008 (ex NN 4/2008)) implemented by Spain for Ciudad de la Luz SA’, Official Journal of the European Union, 16 September, paras 23–24.

16 Ibid., paras 65–79.

17 Ibid., paras 79–81.

18 Ibid., paras 87–88. Spain appealed the Commission’s decision to the General Court; however, the General Court upheld the Commission’s decision. See Judgment of the General Court, Case T-319/12, 3 July 2014, para. 194.

19 For example, see Judgment of the Court of Justice, Case C-482/99, 16 May 2002, para. 71.

20 Association for Financial Markets in Europe and International Capital Market Association (2015), ‘Guide to infrastructure financing’, June, p. 16.

21 For example, Altius completed a royalty transaction with Tri Global Energy. For further details, see Altius (2019), ‘Altius Announces First Renewable Energy Royalty Transaction’, 7 February, accessed 26 March 2019.

22 European Commission (2017), ‘New financial instruments for innovation as a way to bridge the gaps of EU innovation support. Final Report’, April, p. 41, accessed 26 March 2019.

23 For example, Duke Royalty Limited is a Guernsey-registered investment holding company whose shares are traded on the AIM market of the London Stock Exchange. For details, see Duke Royalty, ‘Royalty Finance’.

24 European Commission (2017), ‘New financial instruments for innovation as a way to bridge the gaps of EU innovation support. Final Report’, April, p. 11, accessed 26 March 2019.

25 Typically, if the project generates sufficient cash flows to service the royalty payments, these payments should not vary if costs fluctuate. In contrast, cash flows to shareholders are likely to be more volatile. Norton Rose Fulbright (2017), ‘Royalty finance – the new normal?’, August, accessed 26 March 2019.

26 For example, see Duke Royalty, ‘Royalty Finance’, accessed 26 March 2019.

Download

Related

Ofgem’s RIIO-3 Sector Specific Methodology Decision

On 18 July 2024, Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Decision (SSMD) for the forthcoming RIIO-3 price control period for electricity transmission (ET), gas transmission (GT) and gas distribution (GD) networks.1 This follows Ofgem’s consultation on the matter in December 2023.2 RIIO-3 will last for… Read More

The future funding of the England & Wales water sector: Ofwat’s draft determinations

On Thursday 11 July, Ofwat (the England and Wales water regulator) published its much anticipated Draft Determinations (DDs). As part of the PR24 price review, this sets out its provisional assessment of allowed revenues and performance targets for AMP8 (2025–30)—and will be of great interest to water companies, investors,… Read More