It’s a tough one: Ofwat’s PR19 methodology

Ofwat’s consultation paper details how it proposes to set allowed revenues for the 16 water companies in England and Wales over 2020–25.1 It also puts in place arrangements to help introduce markets at various points in the water and wastewater value chain.2

The methodology has wide-reaching implications, and not only for the water companies themselves. For example, while other regulators have published their strategic vision for future price reviews,3 Ofwat is the first to set out its proposals in detail—in particular on key assumptions such as allowed returns.

Now that the dust has settled—and sufficient time has elapsed to digest the 280 pages (plus 15 appendices)—we can take a look at the most important messages from the paper.

Upping the ante

Ofwat has been signalling for some time that PR19 will be a challenging review. Within a year of publishing the final determinations for the previous price review, PR14, its Chief Executive, Cathryn Ross, was already managing expectations:4

I can share with you today some of the things we do already know will be important for PR19. And I want to say now that if you thought PR14 was a challenging review, and you’re expecting an easier time of it in PR19, you need to think again.

The methodology for PR19 follows through on this statement of intent—with Ofwat seeking to push forward the industry efficiency frontier by challenging the water companies on several fronts.

Challenge across the board

Promoting markets

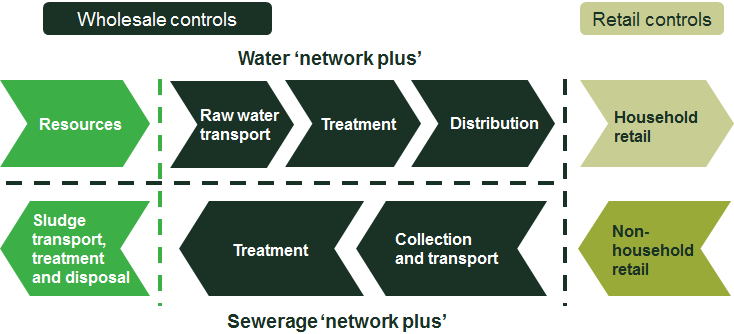

In PR14 Ofwat introduced separate binding controls for wholesale and retail activities. For PR19, it is taking this to the next stage by setting separate binding controls to cover some of the different wholesale activities. This will result in four controls:

- water resources—covering raw water sourced from rivers, reservoirs and boreholes;

- water ‘network plus’—covering raw water transport, water treatment and distribution;

- sewerage ‘network plus’—covering wastewater collection and treatment;

- bioresources—covering sludge transport, treatment and disposal.

Figure 1 provides an overview of the separate controls in the context of the water sector value chain.

Figure 1 Separate controls at PR19

The rationale for this disaggregation is to provide targeted incentives and pave the way for markets to develop in what Ofwat regards as contestable areas—namely, water resource development and sludge transport, treatment and disposal.5

In the area of water resources, Ofwat envisages:

- more water trading between neighbouring companies (‘bulk supplies’) than currently takes place—although the regulator has not proposed further incentives to achieve this beyond those set out in PR14;

- a bidding-in market—where incumbent companies invite neighbours and third parties to submit proposals for resources development or water demand management (competition for the market);

- a bilateral market—in which retailers contract directly with upstream providers of water resources, with an access charge paid to the network business (competition in the market).

However, this last market depends on government activation of the relevant provisions of the Water Act 2014. Ofwat notes that this market would in any case be small and nascent up to 2025.

Bioresources is an interesting area, as companies have improved their anaerobic digestion capabilities over recent years—a process of digestion of sludge that generates methane, which in turn can be used to produce electricity, gas-to-grid and fertiliser. As such, sludge is increasingly viewed as a valuable resource as opposed to a waste product.

In this particular area Ofwat envisages more trading between companies where this is economic—for example, based on differences between companies in unit costs or energy yield; and entry by ‘other organic waste’ providers—which currently process food, beer and industrial organic waste.

The disaggregation of wholesale controls has led to the consideration of several regulatory issues, including:

- approaches to ‘carving up’ the existing regulatory capital value (RCV) among the different activities—Ofwat has proposed an ‘unfocused’ approach for water resources (based on an apportionment), and a ‘focused’ approach for bioresources (based on economic value);

- the cost of capital for the different activities—although at this stage Ofwat is not convinced that different wholesale services should be subject to a different cost of capital;

- how the risk of asset-stranding will be mitigated—Ofwat regards pre-2020 assets as protected, although it has not proposed an explicit mechanism for how this protection should be enacted;

- exposure to revenue risk—for all wholesale controls except bioresources Ofwat has proposed a ‘total revenue control’, thereby limiting exposure to revenue risk. In contrast, bioresources is subject to an ‘average revenue control’, exposing companies to risk (both upside and downside);

- market developments and the gains that might be delivered—as is evident from the above discussion, Ofwat is envisaging the potential development of a number of markets at the wholesale level (competition both in and for the market). Which markets actually develop in practice remains to be seen.

Ofwat also envisions that, for projects with a whole-life total expenditure (TOTEX) of £100m or more, companies should consider direct procurement—where a third party delivers the work. This competition for the market applies to the entirety of wholesale services (except bioresources).

The above discussion focuses on wholesale activities. As an aside, the non-household retail market (covering England and Scotland) was opened up in April 2017, and Ofwat is now considering whether to regulate this market in the same manner going forward. Ofwat will nonetheless retain retail price controls for households in England and Wales—since these customers cannot choose their retailer.6 Ofwat is, however, considering moving to a three-year control.

Customer engagement and outcomes

Ofwat is expecting to see a step change in how companies engage with their customers. The regulator has confirmed its existing policy of continuing with the consumer challenge group model of customer engagement, which involves such groups giving independent assurance to Ofwat on the quality of a company’s customer engagement and the extent to which this engagement is reflected in the business plan.

Furthermore, Ofwat expects companies to employ a range of techniques to engage with customers on their priorities for service improvements, and their willingness to pay for these improvements. Ofwat wants companies to:

- use ‘revealed preference’ methods rather than relying solely on ‘stated preference’ methods (as used extensively in PR14) to determine willingness to pay;7

- make better use of customer, operational and social media data to target service improvements;

- use behavioural science to nudge customers into better behaviours (e.g. in relation to water efficiency and sewer blockages);

- involve customers and communities as knowledgeable active participants in co-developing and co-delivering solutions.

Ofwat is also proposing several changes to make the current outcome delivery incentives (ODIs) agreed between companies and their customers at PR14 more challenging, by:

- adopting 14 common performance commitments with standard definitions that cover areas such as leakage, supply interruptions, environmental performance, resilience and asset health;

- requiring companies to set their performance-level targets at least at the forecast upper quartile in 2024–25 for four of these common performance commitments.8 Companies would be required to achieve this level of performance in 2020–21 (i.e. with no glide-path);

- removing the cap on ODI rewards and penalties (which for PR14 was set at +/-1% to +/-2% of return on regulated equity, RORE), and setting an indicative range for the overall value of ODIs equal to +/-1% to +/-3% of RORE;

- having in-period ODIs as the default (rather than adjustments at the end of the regulatory period);

- introducing new measures of customer experience for household customers (the customer measure of experience, C-MeX) and developers (the developer services measure of experience, D-MeX). Ofwat is proposing that +/-12% of household retail revenues would depend on C-MeX performance.

Ofwat states that the above measures will mean that an average-performing company would expect to incur penalties on its ODI package.9

In sum, therefore, Ofwat is proposing a two-pronged approach—a more challenging approach to assessing companies’ business plans at PR19 in terms of what constitutes ‘good engagement’, and more challenging incentives for companies to deliver on outcomes.

Wholesale cost assessment

Things will not be any easier for companies on efficiency assessment. As in PR14, Ofwat is proposing to follow an econometric approach to set efficient wholesale cost allowances. While little detail has been provided on what these models will look like, the regulator has said that it proposes to:

- use a combination of top-down (aggregate) models and more granular benchmarking analysis;

- examine granular cost models for water resources and the bioresources controls (as well as modelling them in combination with the other activities in the wholesale value chain);

- adopt a range of approaches to assess enhancement expenditure, including TOTEX econometric models (where appropriate), separate enhancement cost models (where there is sufficient data), forecast data, and true-ups for unconfirmed environmental obligations.

In terms of overall policy decisions, Ofwat is proposing several changes that are likely to result in companies facing a tougher cost-efficiency challenge, including:

- introducing an assumption for frontier shift efficiency (e.g. based on economy-wide productivity improvements);

- having no glide-path to the efficient level of costs;

- where special cost factors are considered (bespoke adjustments for company-specific issues not captured in the efficiency models), applying these symmetrically: for upward adjustments to a company’s cost allowance, Ofwat may apply downward adjustments to other companies’ cost allowances;

- considering whether an efficiency target that is more stringent than the PR14 upper-quartile benchmark is appropriate.10

Ofwat will consider whether to provide more details on the wholesale models over the course of 2018 as these are developed.

Wholesale allowed returns

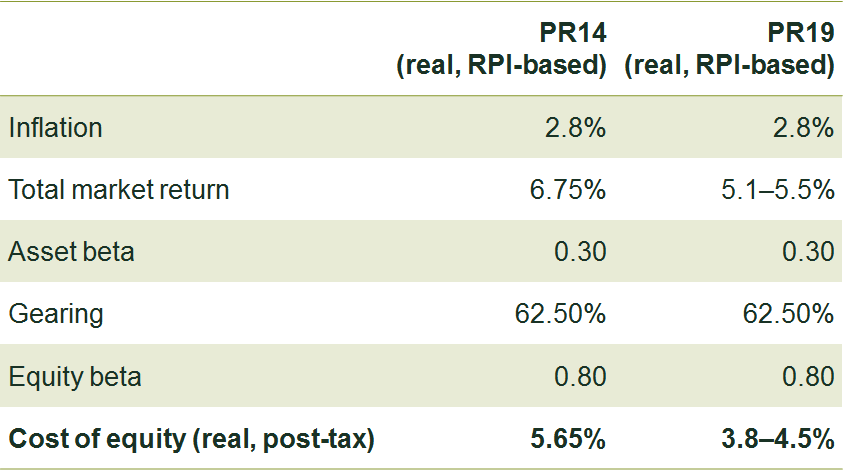

For the four wholesale controls (see Figure 1 above), Ofwat will continue with the RCV/WACC model of remuneration. In relation to allowed returns, placing weight on market conditions expected over 2020–25, Ofwat proposes a reduction in the allowed cost of equity (based on a much lower estimate of total market returns than used in PR14).

In determining that expected market conditions would merit a reduction in the cost of equity, Ofwat has focused on the following evidence:

- current evidence on the risk-free rate, with negative yields on the ten-year average of UK government index-linked gilts;11

- transaction and trading data, including on recent transactions that imply a market-to-asset valuation ratio of around 1.5 times (such as the Severn Trent acquisition of Dee Valley Water in 2017);12

- regulatory precedent, including Ofcom’s recent consultation for wholesale local access that proposes a total market return of 6.0%.13

For comparability purposes, the consultation gives a range for the total market return of 5.1–5.5% (in real RPI terms). Using the PR14 assumptions for gearing and asset beta gives a cost of equity range of 3.8–4.5% (in real RPI terms), as compared with the PR14 assumption of 5.65% (in real RPI terms). Table 1 provides a comparison between the cost of equity allowance at PR14 and the range proposed for PR19.

Table 1 Comparison of allowed cost of equity between PR14 and PR19

While Ofwat acknowledges that it is too early to take definitive views on the cost of equity for PR19, it has set a clear direction of travel for when it returns to this area in its final methodology in December. This area in particular is likely to have implications that stretch far beyond the water sector.

The methodology includes several other proposals. For example:

- there will be no expectation that smaller water-only companies have higher risk and should earn higher returns;

- the cost of new debt will be indexed to an efficient benchmark (i.e. cost of debt indexation). In this regard, Ofwat will base the allowance for the cost of new debt on changes in corporate bond indices (iBoxx 50:50 mix of A and BBB indices). It will adjust for differences between the upfront allowance and the outturn iBoxx index at the end of the 2020–25 period;14

- the cost of embedded debt will continue to be set based on fixed allowances.

Raising the bar on business plans

Ofwat is building on the fast-tracking process introduced for enhanced business plans for PR14, which led to South West Water and Affinity Water receiving earlier draft determinations and additional rewards. It is proposing four categories of companies:

- exceptional status, which will be awarded for plans that are considered to be high-quality, to have significant ambition, and to be innovative;

- fast-track status, which will be awarded for plans that are high-quality and do not require material intervention to protect customer interests, but which do not bring the company exceptional status (for example, as they are not ambitious or innovative enough);

- slow-track status, which will be assigned for plans where material interventions are required in some areas in order to protect the interests of customers;

- significant scrutiny status, which will be assigned for plans that fall short of expectations and where material interventions are required in order to protect the interests of customers.

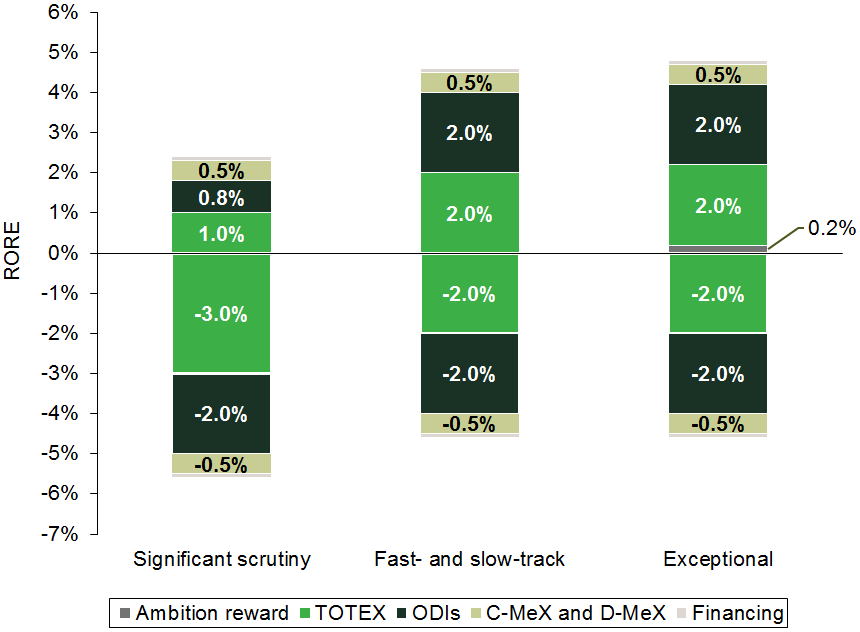

As at PR14, companies will be incentivised with a range of financial, procedural and reputational rewards:

- exceptional plans will receive a RORE reward equivalent to +0.2% RORE; however, fast-track plans will receive no reward;

- exceptional and fast-track plans will receive an earlier draft determination (March/April 2019), with fewer interventions than with slow-track and significant scrutiny plans;

- significant scrutiny plans will receive reduced cost-sharing rates (i.e. they will bear a higher proportion of underperformance, and keep a lower proportion of outperformance).

While Ofwat’s methodology is challenging, the benefit is that the very best-performing companies will have the potential to receive higher rewards. Figure 2 shows the range for RORE around the cost of equity that is included within the cost of capital. The figure shows that exceptional, fast-track and slow-track companies will be able to attain outperformance worth up to 5% of RORE (in addition to the allowed cost of equity assumption in the cost of capital). The question that companies will no doubt be asking, however, is whether such outperformance will be attainable in practice—given the challenging nature of the overall package.

Figure 2 RORE ranges for business plan classifications

Evidently, companies will not want to be placed in the ‘significant scrutiny’ category—given that this means the prospect of significantly lower returns.

Concluding comments

Relative to PR14, where companies may have seen favourable elements in Ofwat’s proposals in some places and less favourable elements in others, PR19 will be tougher across the board in terms of:

- outcomes—there will be higher hurdles for assessing customer engagement, and strengthened ODIs (including no glide-path to the upper quartile for comparative measures);

- wholesale TOTEX—there will be a tougher efficiency challenge (including no glide-path, and a target that may be above the upper quartile);

- WACC—there will be downward pressure on the components;

- business plan assessment—there will be a tougher assessment framework in the round.

While incentive regulation is intended to be challenging and to replicate the forces that are present in a competitive market, this needs to be balanced against the fact that water is an essential service and that water companies need to be able to finance their functions. Do Ofwat’s proposals go too far this time? There are various degrees of competitiveness, but in a ‘reasonably competitive’ market would a company be able to achieve upper-quartile (or higher) performance overnight? It will be interesting to see what emerges when Ofwat publishes its final plans in December, and to what extent other regulators head in a similar direction going forward.

The UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) will also be keeping a close eye on developments. Ultimately, companies can appeal their package to the CMA if they do not think it is financeable. This is not a one-way street for companies (things can go down as well as up), and appealing takes up valuable management time.15 Companies will therefore first want to ensure that the deal on the table from Ofwat in 2019 is realistic. However, it is for companies to convince Ofwat of their case in their business plans—which will be submitted in September 2018. In this respect, Ofwat has raised the bar on what constitutes a robust evidence base.

1 Ofwat (2017), ‘Delivering Water 2020: Consulting on our methodology for the 2019 price review’, July.

2 For example, see Ofwat (2015), ‘Water 2020: regulatory framework for wholesale markets and the 2019 price review’, December; and Ofwat (2016), ‘Water 2020: our regulatory approach for water and wastewater services in England and Wales’, May.

3 The UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) has published strategic themes for the next regulatory review of Heathrow Airport—see Civil Aviation Authority (2016), ‘Strategic themes for the review of Heathrow Airport Limited’s charges (H7): a discussion document’, March. Ofgem, the energy regulator for Great Britain, has published key principles for the next regulatory review in energy networks (i.e. RIIO-2) in Ofgem (2017), ‘Open letter on the RIIO-2 framework’, July. The Office of Rail and Road (ORR) has published a consultation on the overall framework for regulating Network Rail, in Office of Rail and Road (2017), ‘Overall framework for regulating Network Rail: a PR18 consultation’, July. The Water Industry Commission for Scotland (WICS) has published its methodology for the Strategic Review of Charges 2021–27—see Water Industry Commission for Scotland (2017), ‘Innovation and collaboration: future proofing the water industry for customers’, April.

4 Ross, C. (2015), ‘Sector challenges and Water 2020’, 15 October.

5 For an overview of Ofwat’s proposals, see Oxera (2016), ‘Water 2020: do Ofwat’s upstream market proposals hold water?’, Agenda, February.

6 Meanwhile, government policy on whether households should have a choice of retailer remains unclear. Having undertaken an assessment of the issues, in 2016 Ofwat left the decision of whether to open up the household market in England with the UK government. In March 2017 the government stated that it wanted to understand the evidence better before Ministers could make a decision (see Defra (2017), ‘The government’s strategic priorities and objectives for Ofwat’, draft for consultation, March). Arguably, even if a decision were made, pursuing it would require legislative time—which may be at a premium given the current focus on Brexit.

7 Much of water and wastewater provision involves the delivery of non-market goods (goods that are not directly traded in markets, such as clean beaches), so customer valuations are not directly observed. In such cases, stated preference techniques are used, which involve surveying people to identify customer willingness to pay. Revealed preference techniques explore actual customer behaviour and prices for a related good (for example, travel costs).

8 Those that will be assessed on a comparative basis at PR19—water quality compliance, supply interruptions, sewer flooding, and wastewater pollution incidents.

9 Ofwat (2017), ‘Delivering Water 2020: Consulting on our methodology for the 2019 price review’, July, p. 72.

10 Ofwat (2017), ‘Delivering Water 2020: Consulting on our methodology for the 2019 price review’, July, p. 165.

11 For example, see Ofwat (2017), ‘Delivering Water 2020: consultation on PR19 methodology Appendix 13: Aligning risk and return’, p. 16.

12 Water Briefing (2017), ‘Severn Trent completes Dee Valley Water acquisition’, 17 February.

13 Ofcom (2017), ‘Wholesale local access market review – annexes’, March, p. 263.

14 Ofwat (2017), ‘Delivering Water 2020: Consulting on our methodology for the 2019 price review’, July, p. 210.

15 See Oxera (2015), ‘The CMA’s determinations for Bristol Water: an appealing process?’, Agenda, December.

Download

Related

How can economics help governments decide how to spend scarce public funds?

In the UK, and across Europe, there are many public-funded areas crying out for more investment. However, the context of low growth, high levels of public debt and public interest payments, mean that tough decisions on spending priorities across public services, infrastructure and social security have to be made. In… Read More

Assessing the financial regulation of European football clubs

The roar of the crowd, the thrill of the game—football is a global phenomenon. With rising TV audiences and lucrative commercial deals, it has become big business. Money has surged into the game and changed the incentives for clubs, their executives and owners. So, what needs to be done to… Read More