Is it time to review the pay review bodies?

Waves of strike action across the public sector have reignited interest in how governments set public-sector pay. In the UK, pay review bodies (PRBs) play a critical role in the pay-setting process, by advising government on pay settlements for almost half of public-sector workers. Should PRBs be reformed in order to remain relevant, and to ensure that the outcomes of the pay review process are seen as legitimate?

For governments, making trade-offs between pay and spending on other priorities has never been easy. However, these decisions have become increasingly difficult in recent times against a backdrop of relatively high inflation and continued low growth.

This issue has come into sharp focus in the UK in early 2023, following an agreement reached between government and health unions on pay for around 1.4m National Health Service (NHS) staff.1 This agreement covers NHS ‘Agenda for Change’ (AfC) staff—a group that includes nurses, midwives and other healthcare professionals.

Initially, the government insisted that it was unwilling to reopen the 2022/23 pay offer for AfC staff, having accepted the recommendation from the independent NHS PRB for a rise of just over 4%.2 However, on 16 March, the government announced an offer of an additional 2% on top of individuals’ basic salaries for 2022/23, as well as a one-off ‘NHS Backlog Bonus’ worth at least £1,250 per person. The government also announced an offer of a 5% pay increase for staff for 2023/24, effectively overriding the PRB process for the following year.3

Commenting on the deal, the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer, Jeremy Hunt, said:

We had an independent process that happened last year. But we also recognise there was a lot of cost-of-living pressures […] I’m confident that the award that we’ve given will still allow inflation to follow its downward trajectory.4

As the holder of the purse strings, decisions on public-sector pay ultimately rest with the government. However, its recent pay offer for NHS staff raises questions as to why the PRB originally recommended a less generous settlement, and whether the framework within which it provides its advice could be improved. In other words: is it time to review the PRBs?

How pay review bodies work

There are eight PRBs in the UK, advising on pay for roughly 45% of public-sector employees (approximately 2.5m people). PRBs advise the government on pay for a wide range of professionals:

- dentists and doctors;

- wider non-medical NHS staff;

- schoolteachers;

- the police;

- senior civil servants;

- the armed forces;

- prison guards;

- National Crime Agency staff.

PRBs have between six and eight members, with chairs appointed by the Prime Minister and other members usually appointed by the relevant Secretary of State. They are supported by the Office of Manpower Economics (OME), which acts as the independent secretariat for the bodies. The OME conducts research on a range of topics relating to pay and workforce management, including employee engagement, pay progression and workforce demographics.5

Each PRB has its own terms of reference, which are set by the relevant Department’s Secretary of State. Terms of reference sometimes vary across PRBs, reflecting the unique circumstances of each public service. For example, the terms of reference for the Police Remuneration Review Body and the National Crime Agency Remuneration Review Body both state that—when issuing their recommendations—they must take into account the inability of employees to take strike action.6

Nevertheless, most PRBs’ terms of reference indicate that they must consider:

- the need to recruit, retain and motivate staff;

- the funds available to the relevant Departments;

- the government’s inflation target.7

PRBs’ terms of reference are supplemented by ‘remit letters’, which are issued by the relevant Secretary of State each year. These indicate which factors the body should pay particular attention to in that year.

In some years, PRBs have been required to make recommendations that are consistent with a particular cap on overall pay growth. For example, public-sector pay growth was limited to an average of 1% per year between 2013 and 2017, during which time Departments sought recommendations from PRBs regarding how the aggregate pay award could best be targeted across different pay bands.8

After remit letters are issued, PRBs begin receiving evidence regarding the appropriate settlement for the relevant pay year. Advice is received from various stakeholders, including unions, employers and the Treasury. PRBs may also commission research from the OME at this stage, to help inform their recommendations.

Finally, PRBs make a recommendation to the government on the appropriate level of pay, taking into account both the evidence received and their remit letters and terms of reference.

The government is under no obligation to implement the PRBs’ recommendations, and it retains total discretion to accept these in full, accept them in part,9 or reject the recommendations outright.

Are we asking PRBs the right questions?

It is not the role of the PRBs to make decisions. Their role is to provide advice to the government on an extremely sensitive topic, and what is often a difficult balancing act.

It is easy to see the value in removing the politics from this process as much as possible, and letting experts provide impartial advice after weighing up the evidence. Nevertheless, while these experts may be independent, their advice is not provided in a vacuum: their terms of reference and remit letters influence both what they can advise on and how they balance competing priorities.

Asking PRBs to consider the need to recruit, retain and motivate staff when advising on pay is uncontroversial (indeed, from an economics standpoint, this is the only reason for compensating labour).10 However, while other criteria that PRBs are asked to consider may at first appear to be reasonable, further examination suggests that it may be unwise to ask them to take these other factors into account.

Affordability

In the long run, public-sector pay must be funded through taxation.11 Given this, if prices increase then—all else being equal—governments can either:

- increase taxation;

- reduce output; or

- implement real-terms pay cuts.

For this reason, therefore, affordability must be reflected in decisions on pay, given the fiscal implications arising from any settlement. Ignoring the state’s capacity to fund salary increases when deciding on pay for nearly half of the public sector would be illogical—and arguably reckless.

What’s less clear is whether affordability should be taken into account when advising on pay, and if so, how.

There are two issues here. First, adjusting proposed levels of pay to account for affordability constraints inevitably means that—all else being equal—PRBs will recommend lower levels of pay than those that they consider to be necessary to recruit, retain and motivate staff.

This may be deemed an acceptable outcome, if the alternative is that governments simply ignore PRBs’ recommendations on the grounds that they have not considered affordability.

However, if this is the case, it would be helpful if PRBs could make this clear in their advice to government, while also outlining the implications for staffing levels and public services in the relevant sector of paying below the market rate due to affordability constraints.

Contrast this with the recommendation of the NHS PRB for the 2022/23 pay round, which concluded that:

Our recommendations […] go some way to reduce the risk that pay is a reason to leave NHS service; to protect the service from additional temporary workforce costs; and to protect risks to patient care from the impact of increased vacancies and an overstretched workforce.[emphasis added]12

Arguably, this statement provides insufficient clarity to policymakers regarding the likely impact that considering ‘affordability’ could have on public services. While politicians may consider that some ambiguity helps to make proposed pay settlements more ‘sellable’, transparency is needed to ensure that ministers are fully apprised of the trade-offs that they face when making decisions on pay.

Second, it is important to realise that, by the time PRBs are asked to advise on pay, Departmental budgets have already been set. This was highlighted in the government’s submission to the NHS PRB for the 2023/24 pay round, which stated:

Through the current financial settlement provided by HM Treasury to the department and reprioritisation decisions, funding is available for pay awards up to 3.5%. Pay awards above this level would require trade-offs for public service delivery or further government borrowing.13

The implication is that PRBs are assessing these trade-offs ‘blindly’. That is, if they recommend a pay rise above that originally assumed by the government during the relevant spending round period, they do not know whether—if accepted—it will be funded:

- from the relevant Departments’ existing budget;

- from somewhere else (i.e. via other parts of government expenditure, or via additional borrowing or taxation).

So, is there a way to make these trade-offs more transparent, and ensure that PRBs are not assessing them ‘blindly’?

One option could be for governments to stop asking PRBs to consider affordability when advising on pay, and assume that any pay rise would be funded through additional borrowing and/or taxation. Governments would still have the flexibility to accept or reject PRBs’ recommendations.

However, since PRBs would recommend pay increases without taking into account funding constraints, the difference between the pay rise recommended by the PRB and the final figure selected by the government would provide some indication of the trade-off that the latter has made (i.e. whether it has prioritised staff numbers and maintaining public services, or broader fiscal objectives).

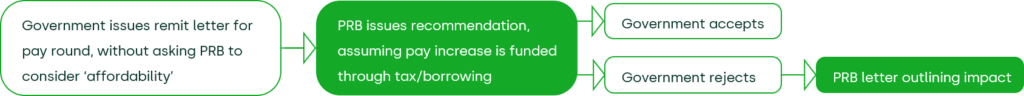

PRBs could provide further transparency by publishing a formal statement if their recommendation is rejected, outlining their view of the likely impacts of the government’s final decision. This is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 PRB process without requirement to consider affordability

While this approach benefits from greater transparency, it has two key drawbacks. First, as noted above, any process under which PRBs do not take account of affordability risks the government simply rejecting their recommendations by default. Second, for an approach like this to work, a more fundamental restructuring of the budgetary process may be necessary (e.g. by excluding staff costs from Departmental expenditure limits set through government spending rounds, on the assumption that funding for these costs will be agreed later).

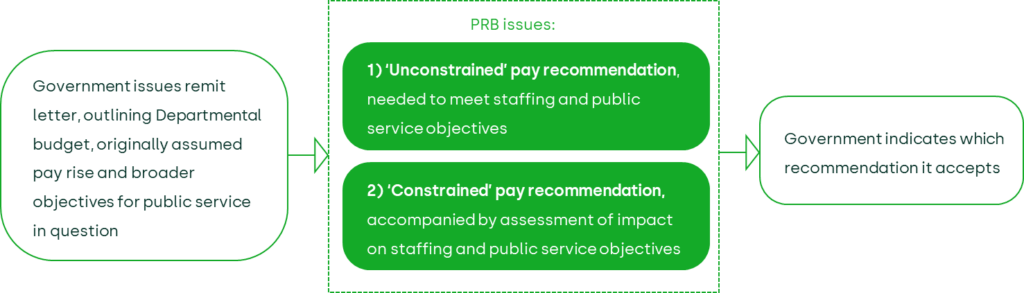

An alternative approach might involve asking PRBs to issue two separate recommendations:

- an ‘unconstrained’ recommendation, which assumes that any pay rise in excess of that assumed during the original spending round will be funded through additional borrowing/taxation;

- a ‘constrained’ recommendation, which assumes that any pay rise in excess of that originally assumed by government can be funded only from the existing departmental budget.

This is shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 PRBs issue ‘constrained’ and ‘unconstrained’ recommendations

This approach would provide greater transparency of the trade-offs facing the government, and—where governments accept the ‘constrained’ pay recommendation—clarity around the implications of this decision for the public services in question.14 While providing such clarity on the government’s preferred trade-off might be seen as creating political difficulties, this approach could equally provide more robust evidence for the government to use when defending its decisions.

Inflation

On first inspection, asking PRBs to take the government’s inflation target into account appears reasonable. Changes in public expenditure can affect the wider macroeconomy, meaning that decisions on public-sector pay should reflect some assessment of inflation risk. The risk of more generous pay settlements exacerbating inflation has taken particular prominence recently, with remit letters to all PRBs for the 2023/24 pay round including the following sentence:

In the current economic context, it is particularly important that you also have regard to the government’s inflation target when forming recommendations.15

However, it is unclear whether it makes sense to ask PRBs to consider the impact of pay awards on economy-wide inflation when forming their recommendations. To begin with—as with affordability—asking PRBs to factor inflation risk into their recommendations means that recommended pay increases are likely to be below the levels needed to recruit staff and maintain public services.

There are also legitimate questions about the appropriateness of seeking to achieve macroeconomic policy objectives such as price stability by adjusting wages in a single sector of the economy. As Ben Zaranko, Senior Research Economist from the Institute for Fiscal Studies, notes, ‘[t]here is no reason pay review bodies should be fine tuning [public-sector] wages to affect economy wide inflation’.16

More generally, it is not obvious that higher public-sector pay automatically translates into higher prices. The lack of prices in the public sector (e.g. in schools or the NHS) limits the scope for higher pay awards to put upward pressure on economy-wide inflation via cost-push inflation.

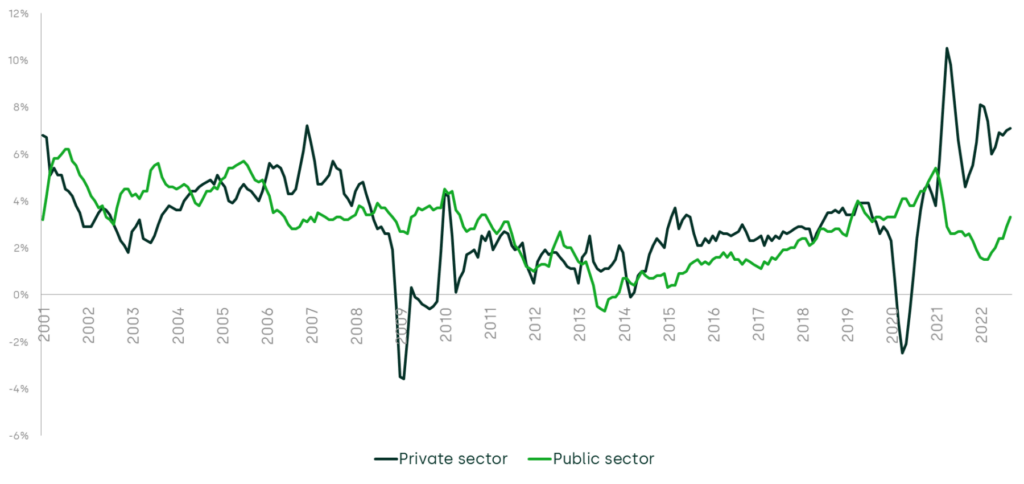

In theory, pay increases could influence inflation where private-sector pay is benchmarked to public-sector pay. However, this is less likely to be an issue if private-sector pay settlements are considerably more generous than public-sector pay settlements. As shown in Figure 3, this is currently the case.

Figure 3 Annual percentage change in average weekly earnings (including bonuses), Great Britain, 2001–present

Of course, higher public-sector pay could generate higher prices via demand-pull inflation. If public-sector employees have higher earnings, this may lead them to spend more, which in turn could lead to higher prices.

However, this rationale for factoring inflation into pay recommendations leads to an uncomfortable conclusion. This is because demand-pull inflation depends on an economic agent’s marginal propensity to consume.

All else being equal, lower-paid workers are likely to have a higher marginal propensity to spend their wages than their better-off counterparts. The implication is that PRBs could decide (at the margin) to give more generous settlements to higher-paid workers at the expense of lower-paid workers, on the grounds that this is less likely to be inflationary. It seems highly unlikely that this was the UK government’s intention when issuing remit letters for next year’s pay round.17

The need for reform

The concept of independent bodies providing advice to governments on pay would appear to be reasonable. Politicians are often subject to short-term political pressures and election cycles—expecting them to make finely balanced judgements with potentially long-lasting effects could easily have undesirable consequences. Given this, the aim of removing politics as much as possible from the pay-setting process is entirely understandable.

It is clear, however, that the existing process has come under significant strain. Earlier in 2023, 14 health unions indicated that they would refuse to submit evidence for the 2023/24 NHS pay round until the government reopened discussions on pay for this year, while the British Medical Association—the main doctors’ union—has described the pay review process as ‘rigged from the start’.18 Failure to reform the system risks PRBs not receiving evidence from key stakeholders in future and—more importantly—compromising the perceived legitimacy of the process.

Fortunately, these challenges are not insurmountable. Much can be achieved by re-evaluating the issues that PRBs are asked to consider when producing their recommendations; assessing how the pay review process can best be harmonised with wider government budgetary processes; and improving the transparency of PRBs’ advice to Ministers on pay settlements and their implications.

1 This is a conditional offer, which remains subject to the outcome of unions’ member ballots.

2 The NHS pay review body recommended an increase to the overall AfC pay bill by an average of 4.8% across England, Wales and Northern Ireland. However, the exact percentage increase varied depending on grade, with band 6 and 7 staff being offered a rise of 4%. See NHS Pay Review Body (2022), ‘Thirty-Fifth Report 2022’, July, p. 162.

3 Department of Health and Social Care (2023), ‘Government and Health Unions agree pay deal paving way for an end to strike action’, 16 March (last accessed 29 March 2023).

4 Heren, K (2023), ‘Chancellor Jeremy Hunt “hopes” for more strike-ending pay deals – as long as they “don’t risk the economy”’, LBC, 16 March.

5 Office of Manpower Economics (2013), ‘An introduction to pay review bodies’, 6 August (last accessed 27 March 2023).

6 See Police Remuneration Review Body, ‘Terms of reference—The Police Remuneration Review Body advises on the pay and conditions of police officers’ (last accessed 17 March 2023); and National Crime Agency Remuneration Body, ‘Terms of reference—National Crime Agency Remuneration Review Body’s terms of reference’ (last accessed 17 March 2023).

7 Institute for Government (2022), ‘Explainer—Pay review bodies’, 19 December (last accessed 27 March 2023).

[8] For example, see letter from Lord Prior of Brampton to the then chair of the NHSPRB, Jerry Cope: Prior, D. (2015), Letter to Jerry Cope, 6 November (last accessed 17 March 2023).

9 For example, in 2022 the government accepted 12 out of 13 separate recommendations issued by the Prison Service Pay Review Body. See Institute for Government (2022), ‘Explainer—Pay review bodies’, 19 December (last accessed 27 March 2023).

10 While the need for employers to pay workers for recruitment and retention purposes is obvious, there is also a large body of established academic literature focusing on how pay can influence levels of worker productivity. The field, ‘efficiency wages’, has become so established in labour economics that it now underpins many macroeconomic studies that attempt to explain the causes of involuntary unemployment. For example, see Akerlof, G. and Yellen, J. (1987), Efficiency Wage Models of the Labor Market, Cambridge University Press.

11 In the short run, governments also have the option of funding pay increases via borrowing.

12 NHS Pay Review Body (2022), ‘Thirty-Fifth Report 2022’, 19 July, p. 161.

13 Department of Health and Social Care (2023), ‘The Department of Health and Social Care’s written evidence to the NHS Pay Review Body (NHSPRB) for the 2023 to 2024 pay round’, 21 February, p. 17.

14 PRBs may struggle to articulate in detail exactly what less generous pay settlements might mean for frontline services. However, if this is the case, it raises questions about how PRBs are assessing these trade-offs in the first place.

15 The exception is the National Crime Agency PRB, which has not yet received a remit letter for the 2023/24 pay round.

16 Giles, C. (2022), ‘UK strikes: are pay review bodies fit for purpose?’, Financial Times, 20 December (last accessed 19 March 2023).

17 Indeed, governments have often sought to shield lower-paid employees from the effects of inflation, by providing additional payments to staff in lower pay bands. See House of Commons Library (2022), ‘Public sector pay’, 28 October, p. 8. This raises a broader question of whether governments should seek to achieve distributional objectives when setting public-sector pay, and if so, how. For example, if a period of high-inflation results in a cost-of-living crisis, one might conclude that the obvious priority should be to concentrate pay increases at the bottom end of the pay scale, to reduce the risk of low-paid workers facing ‘heating or eating’ situations. However, in such circumstances there may equally be an argument for focusing pay rises at the top end of the distribution, if higher-paid public-sector employees have greater flexibility to move to the private sector than their lower-paid counterparts.

18 Campbell, D. and Crerar, P. (2023), ‘Health unions refuse to give evidence to “rigged” NHS pay review system’, The Guardian, 11 January (last accessed 19 March 2023).

Related

Future of rail: how to shape a resilient and responsive Great British Railways

Great Britain’s railway is at a critical juncture, facing unprecedented pressures arising from changing travel patterns, ageing infrastructure, and ongoing financial strain. These challenges, exacerbated by the impacts of the pandemic and the imperative to achieve net zero, underscore the need for comprehensive and forward-looking reform. The UK government has proposed… Read More

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

In the first quarter of this year the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC)1 published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED32 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure… Read More