Competition in the presence of network effects: when fewer is more

In October 2018 the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) cleared Post Office’s acquisition of Payzone’s bill payment systems business. This was a three-to-two merger in a two-sided market with network effects, but the CMA found that the merger was likely to be procompetitive. The case illustrates some important principles for the assessment of mergers in the presence of network effects.

Oxera advised the merging parties on this case. See Competition and Markets Authority (2018), ‘Case ME/6759/18. Anticipated acquisition of Post Office Limited of Payzone Bill Payments Limited, Decision on relevant merger situation and substantial lessening of competition’, 19 October.

Post Office and Payzone both offer over-the-counter payment of bills, subscriptions and services (so-called bill payments systems, BPS). BPS allow customers to make cash payments in different retailers’ premises to settle their utility bills. Customers therefore do not need a bank account or a debit/credit card to pay their bills. Even for those who do have a debit or credit card, there can be benefits of BPS, such as allowing customers to interact with their local retailer rather than with a telephone billing system.

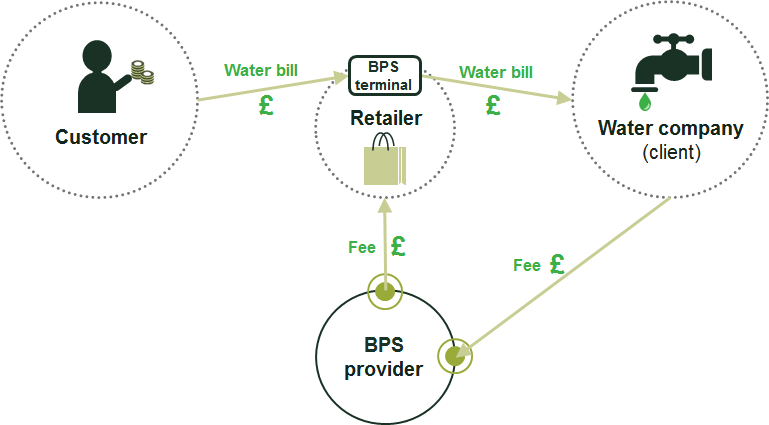

Through BPS, a customer can pay—for example—their water bill at a local retailer that has the relevant BPS terminal, which transfers the bill payment to the water company. In return for hosting the BPS terminal and facilitating the payment, the retailer retains a fee per transaction. This fee is paid by the BPS provider, which in turn is paid by the water company. The retailer may benefit further as the service attracts customers to the store, while the water company benefits from providing its customers with an easy way to pay their bills. Figure 1 illustrates interactions involving BPS.

Figure 1 Stylised illustration of transactions involving BPS

The market in which BPS operates is known by economists as a ‘two-sided’ market. On the one side, there are clients—i.e. companies that issue bills to customers; while on the other side, there are retailers that host the BPS terminals.

Before the proposed acquisition, there were three main providers of BPS in the UK:

- PayPoint, the market leader, with the widest network of retailers and the largest number of clients;

- Post Office, a well-known brand with a smaller and more rural network of retailers with more limited opening hours;

- Payzone, with the smallest network of retailers and clients.

Due to the nature of the market, there are ‘network effects’ between the two sides—i.e. a network has greater value to users on one side the higher the number of users on the other side. Clients are attracted to BPS networks that are able to serve a large proportion of their customers through an extensive network of retailers. At the same time, retailers prefer BPS suppliers with a large portfolio of clients as they benefit from the related footfall at the store. Consequently, Payzone, with the smallest retailer network, was able to attract a limited number of clients, which in turn meant that its network of retailers was small.

Under the current legal frameworks in the EU and in the UK, there is no established single economic principle that can be used to assess unilateral merger effects in a two-sided market. This has to be undertaken on a case-by-case basis, based on the specifics of the merger and the characteristics of the market.

Mergers in network markets: what are the effects?

Direct network effects arise when the potential benefit that each user gains from belonging to a network increases as the number of users increases. Instant messaging services are one example: people are more attracted to a service when a higher number of potential contacts are already using it. In the case of a two-sided market, there may be indirect network effects—i.e. where the value of the service for one user group (e.g. retailers) depends on the size of the network of the other user group (e.g. water companies). It was these indirect network effects that were relevant to the BPS merger.

Network effects can be beneficial to competition and consumers. Mergers involving service-based platforms have a particular potential to generate efficiencies just by increasing in size and therefore reaching economies of scale and lowering search costs for customers. Moreover, there can be efficiencies on the supply side of the market (in this case, the clients) if transaction costs between the platform and the service provider are reduced.1 Network effects can also intensify competition, as for small firms the rewards of having a wider network can be large.2

However, network effects also have the potential to enhance the market position of the largest players. In principle, this can raise entry barriers or lead to a vicious circle where large companies become larger, leading to smaller firms no longer being able to compete. This could result in the market reaching an equilibrium where everyone joins only one of the networks (known as market ‘tipping’) and only one firm, with monopoly profits, is left.

Network effects can therefore play an important role in the assessment of mergers. In such a setting, the relative scale of firms in the market is critical when estimating the effect that a particular merger will have on competition. On the one hand, a merger may lead to an even larger firm, which decreases the ability of smaller firms to compete. On the other hand, if two smaller firms merge, their joint network may allow them to compete more effectively with larger players, thereby potentially increasing competition.

In either case, an assessment of consumer benefits will not just consider prices: the value placed by consumers on being part of a given network can increase following a merger that expands the size of the network, which makes it easier for consumers to find a suitable place to pay their bills. The overall effect is therefore a trade-off between the additional value to consumers from being part of a larger network, and the higher prices, or potentially lower quality, caused by reduced competition in the market.3

This discussion does not imply that in practice all network markets have a tendency towards monopoly—in many markets, network effects exist alongside sustained competition (with regard to credit cards or mobile telephony, for example), as there are countervailing effects that can increase competition. For example, multi-homing—i.e. the simultaneous use of different platforms—is considered by the European Commission as a factor that may mitigate the market power of companies, as the decision to use one service provider does not exclude the use of the service of a competing provider by the same user.4 Multi-homing can therefore represent a source of countervailing buyer power, which mitigates an increase in market power arising from a merger. For example, in the acquisition by Google of DoubleClick, a leading online advertisement provider, extensive multi-homing by publishers and advertisers in the ad service market was one of the factors supporting the Commission’s finding that network effects were not strong enough to induce market tipping in favour of DoubleClick after the merger.5

In the BPS market, clients such as water companies frequently multi-home, as they prefer to use multiple BPS providers so that they can achieve the maximum geographic coverage in terms of retailers. In turn, the larger the number of multi-homing clients—i.e. the more clients there are that offer their services through multiple BPS systems—the more the need for retailers to provide multiple BPS terminals is reduced. Retailers therefore frequently single-home in this market, and the size of the retailer network is a key element on which BPS providers compete.

Why did the CMA clear the BPS merger?

In 2017, the CMA cleared the merger between Hungryhouse and Just Eat, two web-based food ordering platforms.6 The CMA stated that, due to Hungryhouse’s poor performance and loss-making position, it was likely to impose a limited competitive constraint on Just Eat. In both Hungryhouse/Just Eat and Post Office/Payzone, the two-sided nature of the market played an important role, as this market dynamic gave rise to declining competitive pressure from one of the players.

On the other hand, there are cases where competition authorities have found that network effects decrease competition by creating barriers to entry and facilitating the growth of the merging parties’ network to such an extent that the market may tip in favour of the merging parties. For example, the Commission found that the merger between Microsoft and LinkedIn could lead to foreclosure of competition in the market of professional social networks, and consequently a tipping of the market. In fact, the Commission found that the merged entity could leverage on Microsoft’s position in the markets for operating systems and productivity software, by, for instance, integrating LinkedIn features within Microsoft’s products in order to foreclose competitors and extend its client base.7

Therefore, in the presence of indirect network effects and their potential influence on the dynamics of competition in the market, why did the CMA decide to clear the merger? The reasons are set out below.

First, both the BPS market as a whole, and Payzone’s position within it, were in decline. The decline had been driven by the increasing use of online banking and new means of payment that do not involve cash, with the BPS market recording at least a 7% year-on-year decline since 2014/15.8 Payzone’s recent performance reflected this, having lost transaction volume over a prolonged period at a faster rate than that of the whole market. An economic analysis showed that it was unlikely that Payzone would be able to reverse this trend, with client losses expected to lead to corresponding losses of retailer merchants, which in turn would be likely to lead to more client losses (a ‘death spiral’). Hence, the counterfactual against which the merger was to be assessed was one of declining competitive pressure from Payzone.

A second factor was the position of the merging firms in the market. There was little overlap between Payzone and Post Office on the retailer side, as Post Office offers BPS only as part of its overall traditional post office offering, and therefore does not compete for ‘non-post office’ retailers with a stand-alone BPS provision. Moreover, post offices provide greater coverage of rural areas, albeit with more limited opening hours, than Payzone’s network, whose retailers were generally retail multiples and convenience stores with longer opening hours. The parties’ retailer networks could therefore be considered complements more than substitutes and were often regarded as such by clients.

Similar reasoning was applied by the Commission in its decision to clear the merger between Facebook and WhatsApp. Although the two applications enable users to exchange content with a list of contacts, there were a number of key differences between the two services, with Facebook offering a richer social experience with more ways to interact with other users and the possibility to reach a wider audience.9

Finally, and perhaps most decisively, was the position of PayPoint in the market. As the UK’s leading BPS provider, PayPoint was the closest competitor for both parties, due in part to its large network of retailers with coverage across the UK. The positive network externalities enabled PayPoint to expand its client network, positioning itself as the most attractive service provider in the market. Indeed, many clients considered that they had to offer BPS services through PayPoint’s network, even though they were more expensive due to the extensive size of its retailer network.10 The CMA considered that the merged entity would be able to offer an alternative to PayPoint, increasing choice on the client side and competition in the market overall.

Consequently, the CMA found that the merged entity would be better positioned to compete with PayPoint and concluded that the merger was more likely to have procompetitive effects within the market for BPS services.11

Is this a trend?

The CMA’s decision to clear the merger between Payzone and Post Office so soon after Hungryhouse/Just Eat may be interpreted as the CMA being more likely to clear a merger with relatively limited remedies where network effects—in the absence of the merger—appear to be leading to a single strong player. The reality is more complicated, however, and network dynamics are such that a forward-looking counterfactual can go either way. For example, in the first phase of the CMA’s investigation of the merger between PayPal and iZettle, two mobile payment companies, the CMA found that the merger could lead to increasing prices, and that PayPal might face insufficient competition in the UK market.12 The CMA also found that iZettle could potentially provide strong competition for PayPal in an emerging market. The merger is currently under in-depth review by the CMA.

Estimating the right counterfactual is essential, as network effects can be an argument for blocking mergers as well as clearing them. To identify the appropriate counterfactual, a dynamic assessment is required, as network effects could lead to tipping markets. In the Post Office/Payzone merger decision, as well as in Hungryhouse/Just Eat, the CMA has not only assessed the current situation, but also taken into account the future competitive landscape. It has taken into account expectations such as a further declining market (Post Office/Payzone) or entry by other competitors (Uber Eats).

The real trend, if any, is that the CMA is showing willingness to carefully analyse forward-looking counterfactuals, thereby taking into account the dynamics implied by network effects. From an economics point of view, this is to be welcomed.

1 Evans, D.S. (2003), ‘The Antitrust Economics of Multi-Sided Platform Markets’, Yale Journal on Regulation, 20:2, article 4.

2 Katz, M.L. and Shapiro, C. (1994), ‘Systems Competition and Network Effect’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8:2.

3 Roberts, T. (2014), ‘When Bigger Is Better: A Critique of the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index’s Use to Evaluate Mergers in Network Industries’, Pace Law Review, 34:2.

4 For example, see the Microsoft/Skype, Facebook/WhatsApp, and Microsoft/LinkedIn mergers.

5 European Commission (2008), ‘Case M.4731– Google / DoubleClick’.

6 Competition and Markets Authority (2017), ‘Case ME/6659-16. A report on the anticipated acquisition by JUST EAT plc of Hungryhouse Holdings Limited’, 16 November.

7 European Commission (2016), ‘Case M.8124– Microsoft / LinkedIn’.

8 Competition and Markets Authority (2018), ‘Case ME/6759/18, Anticipated acquisition of Post Office Limited of Payzone Bill Payments Limited, Decision on relevant merger situation and substantial lessening of competition’, 19 October, para. 33.

9 European Commission (2014), ‘Case M.7217– Facebook /WhatsApp’, paras 51–56 and 153–158.

10 Competition and Markets Authority (2018), ‘Case ME/6759/18. Anticipated acquisition of Post Office Limited of Payzone Bill Payments Limited, Decision on relevant merger situation and substantial lessening of competition’, 19 October, para. 108.

11 Competition and Markets Authority (2018), ‘Case ME/6759/18. Anticipated acquisition of Post Office Limited of Payzone Bill Payments Limited, Decision on relevant merger situation and substantial lessening of competition’, 19 October, para. 111.

12 Competition and Markets Authority (2018), ‘Paypal Holdings, Inc/ iZettle AB merger inquiry’.

Download

Related

Ofgem’s RIIO-3 Sector Specific Methodology Decision

On 18 July 2024, Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Decision (SSMD) for the forthcoming RIIO-3 price control period for electricity transmission (ET), gas transmission (GT) and gas distribution (GD) networks.1 This follows Ofgem’s consultation on the matter in December 2023.2 RIIO-3 will last for… Read More

The future funding of the England & Wales water sector: Ofwat’s draft determinations

On Thursday 11 July, Ofwat (the England and Wales water regulator) published its much anticipated Draft Determinations (DDs). As part of the PR24 price review, this sets out its provisional assessment of allowed revenues and performance targets for AMP8 (2025–30)—and will be of great interest to water companies, investors,… Read More