Central Perks? Are CBDCs the advent of new money, or a false dawn for banking and payments?

Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) have the potential to significantly change the way the global financial system operates. But what exactly are CBDCs, and what impact are they likely to have if implemented? We look at some of the economics behind this new type of money, as well as the key challenges and trade-offs that central bankers, policymakers and industry are likely to face.

In many countries access to electronic money is (or is becoming) widespread, for example through bank accounts and card payments. The use of physical cash for payments is declining rapidly (a trend accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic). Big Tech companies are venturing into finance and payments, while cryptoassets have seen spectacular rises and falls. All these trends, against a backdrop of increased digitalisation, pose big questions for the future of payments and banking.

In recent years, central banks and policymakers have been considering their own responses to these trends, including the introduction of CBDCs. Looking forward, the possible introduction of CBDCs raises many interesting questions from an economics perspective, including around the fundamental structure of the banking sector and how citizens, businesses and governments use money.

An introduction to money and CBDCs

Despite how often we interact with it, people generally do not have a clear understanding of what money actually is. This is largely because we don’t need to—we trust that the money in our bank account, or the cash in our wallet, has some value that we can use in exchange for goods and services.

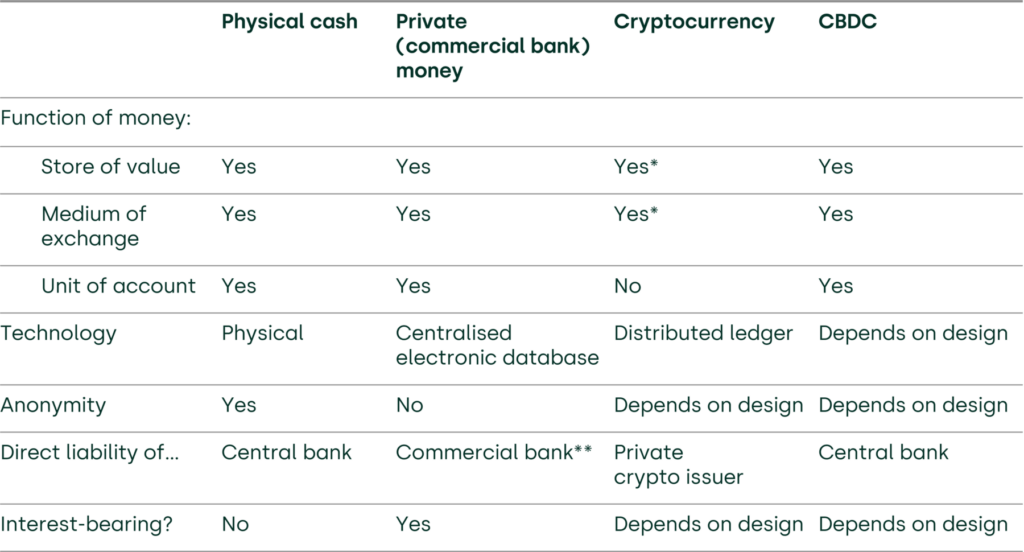

Money is typically described as having three key properties: i) it is a unit of account; ii) it can be used as a medium of exchange, i.e. to make payments; and iii) it acts as a store of value. There are also two types of money: central bank money and private money. How do these two types of money differ?

The only central bank money that is currently directly available for public use is physical cash.1 However, the majority of money held and used by citizens is ‘private’ money issued by commercial banks.2 In essence, the money that you hold in your bank account is a form of IOU from your bank (in other words, a liability of the bank). When you deposit cash with your bank, you are exchanging a central bank IOU for a commercial bank IOU, and the bank credits your account by means of an electronic record. You (along with the rest of society) trust that this IOU can subsequently be traded at par with central bank money at any point in the future.3 This enables private money to be used as a medium of exchange (for instance, through bank transfers or card payments).

This private money is not backed directly by the state. Nevertheless, today’s careful regulation and supervision of banks, combined with deposit insurance schemes,4 mean that retail deposits are typically seen as safe and equivalent to public money.

In many countries, digital money is overtaking cash as the most efficient means of payment. The transition from cash to electronic payments is happening across the world at different speeds, and in some countries card payments are already more widespread than cash and are used for even the smallest routine purchases. Currently, all digital money that is accessible by private individuals is private money (such as retail bank deposits), as individuals do not have direct access to central bank digital money.

Traditionally, the state has been the ultimate primary provider of money. Public money is crucial to the functioning of the two‐layer monetary system. Due to its nature as a central bank liability, it is seen as a safe form of money, and thus acts as an anchor for the monetary system.5 However, some central banks have suggested that it may be at risk from trends such as the shift towards digital payments, the decline of cash usage, and the potential for new payment solutions based on private money (for instance, Big Tech expanding into payments, and the emergence of cryptocurrencies).6

In response to these developments, central banks around the world are considering introducing a digital version of central bank money—CBDCs.7 All major central banks today are at least investigating the potential of CBDCs.8 The European Central Bank (ECB) is currently deliberating various aspects of a potential digital euro, with a decision on whether to start developing and testing a European CBDC due once this investigation stage closes in late 2023.9 In the UK the Bank of England and the Treasury are currently assessing the case for a UK CBDC,10 as is the Federal Reserve in the USA.11 The People’s Bank of China has launched a pilot version of a digital yuan, and the cumulative value of transactions had already surpassed 100bn yuan as at mid-2022.12 A small group of countries have already started issuing their own CBDC that is available widely to the public (at the time of writing, these are Nigeria’s eNaira, the Bahamas Sand Dollar and Jamaica’s JAM-DEX).13

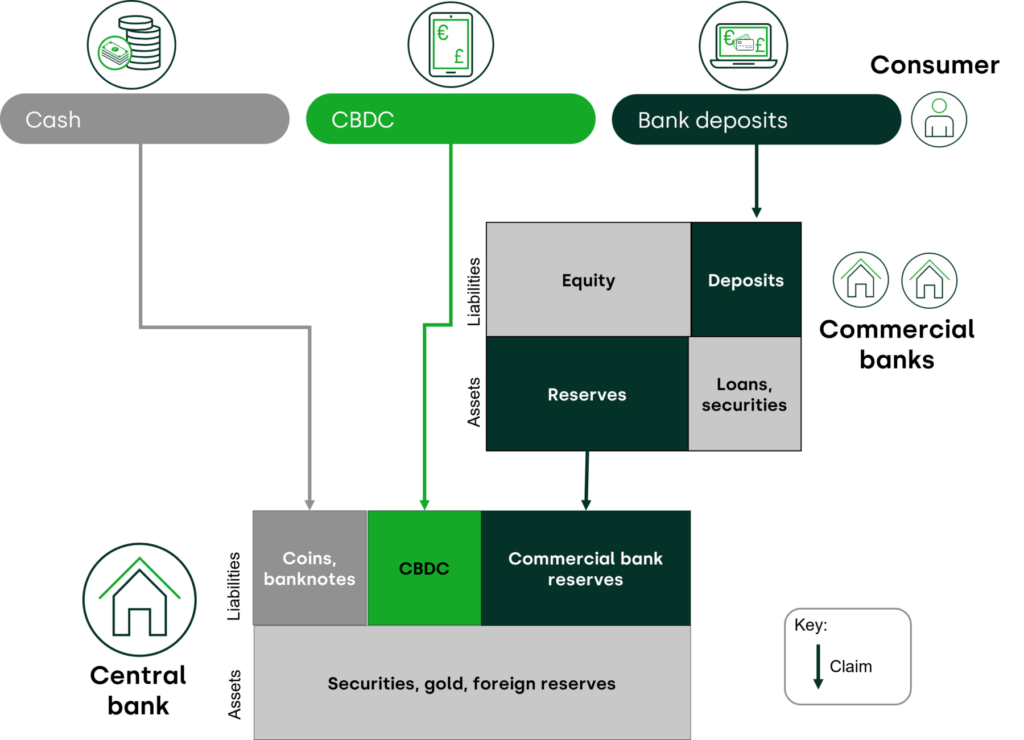

In many ways, CBDCs can be thought of as ‘digital cash’. Both are a direct liability on the central banks rather than liabilities on private financial institutions, as the figure below shows.

Figure 1 Liabilities for cash, electronic payment instruments and retail CBDC

There are some key differences between CBDCs and physical cash. Cash allows payments to be truly ‘anonymous’ in the sense that no data is exchanged when a cash payment is made. It generally does not require identification or ownership of a particular technology such as a smartphone. By contrast, CBDCs by their nature would depend on some form of digital technology (for example, blockchain).14 They would generate data which, in theory, could be collected by the state or private firms.

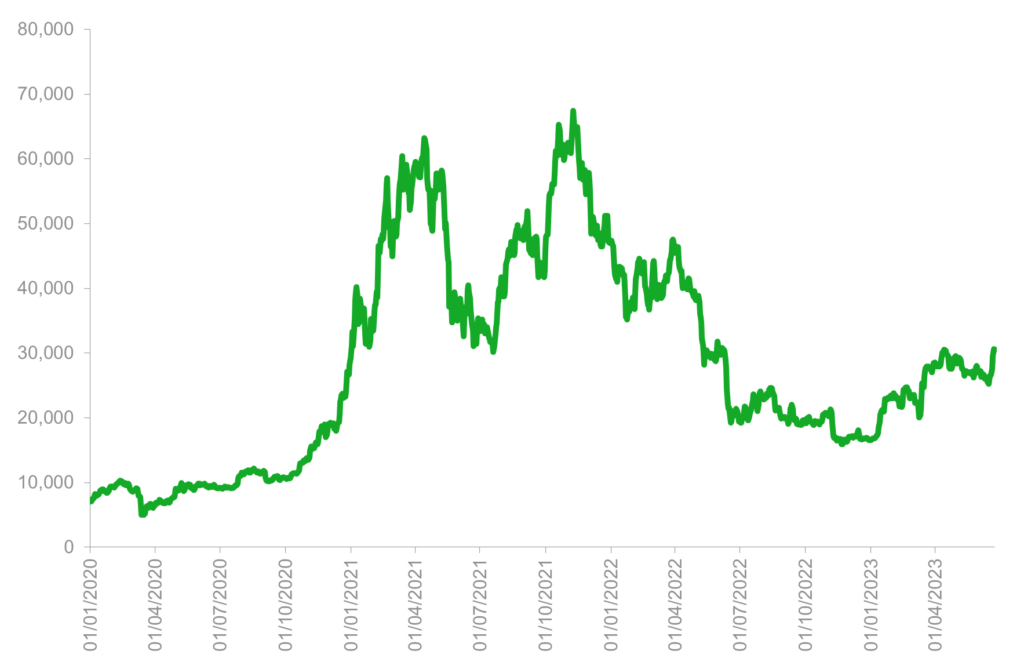

CBDCs could be seen as akin to so-called cryptocurrencies, and particularly a type of cryptoasset known as stablecoins (which are nominally pegged to the value of a traditional currency or basket of assets). However, this comparison is misleading. The price of some key cryptoassets has simply been too volatile to be widely used for payments (see Figure 2). Even stablecoins can be vulnerable to sudden price changes, as the collapse of the Terra stablecoin in 2022 showed.15 To date, in most cases these cryptoassets do not appear to adequately fulfil the three functions of money described above.16

Figure 2 Price of Bitcoin in USD, 2020–23

Source: Oxera analysis of Yahoo Finance data.

By contrast, CBDCs would, by definition, retain a 1:1 value relative to their physical counterparts. They would be a direct liability of the central bank, denominated in the national unit of account. They may therefore present various opportunities and potential use cases beyond physical cash. Some characteristics of different types of currency are set out in Table 1 below.

Table 1 Characteristics of different types of currency

Source: Oxera.

What are the use cases for CBDCs?

As described above, a CBDC could provide a ‘monetary anchor’ in a world that is becoming increasingly digital, and some cite this as an important motivation for investigating the potential development of CBDCs.17 However, it is not clear whether the introduction of a CBDC would be strictly necessary in order to preserve a monetary anchor.18 A CBDC could also give the central bank further levers for monetary policy transmission (although the precise implications of a CBDC for monetary policy are an open question in the literature).19 CBDCs could be used more directly, to target exchange rate or inflation objectives.

In theory, CBDCs could also be used to directly introduce a (targeted) stimulus or even for fiscal transfers. To the extent that CBDCs result in more public money being created, this could also lead to further ‘seignorage’ revenue for the state (seignorage is income earned by a central bank from issuing money).20

CBDCs are sometimes also described as helping to increase competition in spheres such as payments and data—thus driving innovation, quality and price improvements.21 Relatedly, CBDCs could be used to help governments achieve ‘sovereignty’ in these areas (such as monetary sovereignty, whereby the state retains control over money supply and monetary policy).22

However, an introduction of a CBDC could raise challenges. Precisely how these implications would be felt would depend on the design of the CBDC (see the box below).

Design options for a CBDC

- Remuneration and holding limits. Unlike cash, holders of CBDCs could, in theory, be remunerated through interest rates (much like private digital money in some deposit accounts). Such rates could be set at a particular level (for example, they could be linked to an inflation index), vary according to different thresholds, or be set directly by the central bank according to various monetary policy objectives. In addition, it would theoretically be possible to limit the amount of a CBDC that each citizen would be permitted to hold at a given time (or a limit could be placed on the transaction value allowed over a given time period).

- Underlying technology. Technically speaking, a CBDC could be based on distributed ledger technology (such as blockchain), or a more standard centralised database. Some central banks have made it clear that this technology is not necessarily needed for a CBDC. The ECB and Bank of England are currently investigating both centralised and decentralised solutions.1 A major use case for distributed ledger technology is to provide trust in the absence of a centralised party. However, in the case of CBDC, a trusted central party would already exist—namely, the central bank. A related concept is whether a CBDC could be designed to be either account-based (i.e. held as a liability linked to an account at the central bank), or token-based (i.e. held through digital wallets in much the same way as cryptocurrencies operate, allowing for greater anonymity).

- Privacy versus law enforcement. To what extent could or should it be possible for the use of a CBDC to be monitored by the central banks or private sector firms? One attraction of cash is its inherent privacy. However, complete anonymity would prevent private institutions from conducting checks for illegal activity such as money laundering (as they are obliged to do under various anti-money laundering (AML) and know-your-customer (KYC) rules).

- Role of the private sector versus the central bank. A key design question (and one that links all the previous points together) is the nature and extent of private sector involvement in the distribution of this new digital public money. At one extreme, CBDCs could be provided directly by the central bank, for example through current accounts held by the general public at the central bank. Central banks might prefer the provision and distribution of a CBDC to be conducted through private sector partners while retaining monetary control and some regulatory oversight.2

Note: 1 European Central Bank, ‘FAQ on a digital euro’, last accessed 28 June 2023. 2 Banque de France, ‘Digital Euro experiment Combined feasibility – Tiered model’, July.

Implications for the banking system

The introduction of a public digital money that is widely available to the general public could have some important financial stability implications. In large part, this would be due to the substitution away from private money (i.e. money that is held as deposits) at commercial banks. CBDC could become quite attractive for depositors, especially if it is remunerated and if it becomes convenient for use in payments. The safety of public money (as a direct claim on the central bank) could further help to make CBDCs attractive, especially for those with deposits that are too large to be fully covered by regulatory protections against bank failure.

The fact that the introduction of CBDCs could have wide-ranging implications for the banking system and financial stability is well known to policymakers and researchers.23

If a CBDC were to become successful, there are two related risks worth highlighting.

- Structural disintermediation. This refers to a permanent shift in the balance of where consumers’ funds are deposited. In other words, the deposit-taking function of commercial banks could shift largely to the central bank (via third-party non-banks). In such a situation there would be some potentially major implications for banking business models, funding sources, lending, interest rates, etc. With any crowding out of retail deposits there would be fewer deposits at retail banks, and banks would have to look for alternative funding and/or reduce loan amounts or increase loan rates. However, CBDCs could increase competition for retail deposits, including raising deposit rates or potentially increasing deposit volumes and bank lending (albeit this would increase banks’ exposure to interest rate risk). If deposits move to non-bank entities, there could be an opportunity to adapt the credit market—for instance, through lending of CBDC facilitated by non-bank entities. CBDCs would therefore raise many interesting questions around the market design of the current banking system which would need to be thought through carefully.

- Cyclical disintermediation. CBDCs could facilitate runs out of bank deposits in times of financial crisis. Rather than the queues for ATM machines seen in the 2008 banking crisis, depositors could, in theory, move money from commercial banks into public money at the touch of a smartphone. Indeed, while runs from deposits into banknotes might be limited by the risks and costs of storing large volumes of banknotes at home, no such limitations would exist if households were able to hold unlimited amounts of CBDC. And while it is currently possible for bank runs to occur into low-risk ‘electronic’ assets (such as gold-related assets and government debt), this type of run would be disincentivised through the price mechanism (as the safe assets would become very expensive in a crisis). Digital public money, however, would not be subject to such scarcity-related price disincentives. CBDCs may therefore enable larger and faster bank runs.

The precise consequences for the banking sector of the introduction of a CBDC would, to a large extent, depend on the demand for CBDC and the rate of adoption. This, in turn, would depend primarily on whether the CBDC delivers a convenient and good-value service with the right level of privacy, security and ease of use.

Design choices can affect these factors directly. For instance, the ECB is considering a per capita limit on holdings of CBDC in order to reduce the risk of excessive substitution.24 Remuneration could also be designed so as not to make CBDCs too attractive relative to commercial bank deposits. Many forms of measures to moderate CBDC take-up have been suggested, ranging from simple limits to complicated and variable price/quantity measures.25

From the point of view of financial stability, at least in the medium term, a potential CBDC would thus need to be designed carefully, striking the right balance between high adoption rates and displacement of retail deposits. A potential introduction of a CBDC would entail a careful balancing act, in that its success would appear to depend (in part) on it not being too successful.26

Implications for payments

Introducing CBDCs could be a way for policymakers to also achieve policy goals in payments. Central banks have mentioned that CBDCs could introduce more competition to retail payments.27 Some policymakers are keen for new digital payment methods to be developed using CBDC.

In this setting, there is a temptation to see a lot of hype around what CBDCs could do to revolutionise payments. However, to some extent this stems from a confusion about what makes a payment method (and the distinction between digital money and a payment method). Often a payment method is assumed to be simply the transfer of funds from A to B. However, a payment method must also include characteristics that make this transfer possible and available for retail transactions. In practice, this means a involving product that is convenient, secure, reliable and widely accepted. For CBDC to be widely used as a means of payment, it would need to have some value-added services (e.g. user interface such as an app, dispute resolution, and security features).

A CBDC-based payment solution could take the form of a currency that is easily transferable between existing payment methods (such as card schemes). For example, this appears to be the solution adopted in the Bahamas, where consumers can use a CBDC-linked card.28 In some sense a CBDC can, in principle, be seen as the same as any other currency that happens to exhibit a 1:1 conversion to the physical form. Existing infrastructure (both inter-bank and card-based) could thus be used to process payments in CBDCs.

Alternatively, new payment methods based on a CBDC could be developed (current proposals for a digital euro would see the ECB developing a digital euro scheme for retail payments).29 If this is the case, questions would have to be considered around the associated costs and who would bear them. Where would fees be charged, and how much? In all of this, how much is done by the central bank and how much is left to the private sector? The impact of public solutions versus private, and commercial arrangements for competition, innovation, choice and quality would have to be weighed up carefully.

Currently, banking services and payments go largely hand in hand, with the traditional banking system playing a major role in payments. However, there is no reason why this must be the case. Traditionally, retail banks have been the default place for most consumers to receive salary payments and make deposits. In part, this is because these institutions are seen as relatively safe—for instance, through deposit guarantee schemes or other regulatory protections. However, CBDCs (being a direct claim on the central bank) may allow non-bank wallets to provide the same level of perceived security to consumers and thus increase competitive pressure on banks. One interesting potential implication is that payments could be split out from the traditional banking sector (for example, by allowing third parties, fintechs and Big Tech to directly access a secure form of currency). Consumers could, in theory, be able to hold and transfer funds through digital wallets that are not directly linked to a traditional bank account. This development could enable new players to enter the payments space, potentially driving further consumer choice, competition and innovation, while raising interesting questions regarding the business model of the banking sector in the modern economy.

CBDCs: where next?

CBDCs are being investigated by a large number of central banks around the world, and there appears to be real appetite for taking steps towards developing this new form of money.

In order to avoid being a ‘solution in search for a problem’,30 policymakers and researchers need to be clear on the use cases of a potential CBDC, and articulate the design options on key issues (e.g. on privacy). Further research, and detailed economic analysis of the implications for banking, payments and beyond will continue to be required in order for the impacts to be well understood and to allow for a careful design of the potential introduction of this new form of money.

1 Electronic central bank deposits, also known as reserves or settlement balances, are the second type of money issued by central banks.

2 Overnight bank deposits currently account for more than 85% of total money supply. See Ahnert, A., Assenmacher, K., Hoffmann, P., Leonello, A., Monnet, C. and Porcellacchia, D. (2022), ‘The economics of central bank digital currency’, European Central Bank working paper series, No 2713, August.

3 Commercial banks can therefore create new private money, by issuing loans, which are new IOUs from the consumer to the bank. For further background on money in the modern economy, see McLeay, M., Radia, A. and Thomas, R. (2014), ‘Money in the modern economy: an introduction’, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, Q1.

4 This holds up to a limit (for instance, the £85,000 deposit guarantee scheme in the UK, or €100,000 in the EU).

5 Ahnert, A., Assenmacher, K., Hoffmann, P., Leonello, A., Monnet, C. and Porcellacchia, D. (2022), ‘The economics of central bank digital currency’, European Central Bank working paper series, No 2713, August.

6 European Central Bank (2021), ‘Central bank digital currencies: a monetary anchor for digital innovation’, speech by Fabio Panetta, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, 5 November.

7 In this article we focus on ‘retail’ CBDCs that would be available to the general public, rather than ‘wholesale’ versions for use only by financial institutions.

8 Bank for International Settlements (2022), ‘Gaining momentum – Results of the 2021 BIS survey on central bank digital currencies’, BIS Papers No 125, 6 May.

9 European Central Bank, ‘Digital euro’, last accessed 28 June 2023. The European Commission has recently set out a legislative proposal establishing the legal framework for a possible digital euro. See European Commission (2023), ‘Digital euro package’, 28 June.

10 Bank of England, ‘The digital pound’, last accessed 28 June 2023.

11 Federal Reserve (2022), ‘Money and Payments: The U.S. Dollar in the Age of Digital Transformation’, January.

12 Reuters (2022), ‘China’s digital currency passes 100 bln yuan in spending – PBOC’, October.

13 CBDC Tracker (2023), ‘Today’s Central Bank Digital Currencies Status’, June, last accessed 28 June 2023. See also International Monetary Fund (2023), ‘Nigeria’s eNaira, One Year After’, 16 May.

14 More traditional technology can also be used to underpin CBDCs, as explained in the box below.

15 Financial Times (2022), ‘The week that shook crypto’, May.

16 In some jurisdictions regulations are being introduced, in part to improve the safety of markets in cryptoassets. For instance, see the incoming European MiCA (Markets in Crypto-assets) regulations: European Commission (2020), ‘Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Markets in Crypto-assets, and amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937’ COM/2020/593 final, last accessed 28 June 2023.

17 See European Central Bank (2022), ‘The case for a digital euro: key objectives and design considerations’, July.

18 For instance, see Angeloni, I. (2023), ‘Digital Euro: When in doubt, abstain (but be prepared)’, prepared by the Economic Governance and EMU scrutiny Unit at the request of the ECON Committee, section 5.

19 See, for example, Infante, S., Kyungmin, K., Anna, O., Andre, F.S. and Robert, J.T. (2022), ‘The Macroeconomic Implications of CBDC: A Review of the Literature’, Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2022-076, Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

20 For an explanation of seignorage and the possible interactions with a CBDC, see Bank for International Settlements (2018), ‘Central bank digital currencies’, Markets committee, Annex C.

21 See, for example, European Central Bank (2022), ‘The economics of central bank digital currency’, Working Paper Series No 2713, August, section 3.4.

22 See, for example, European Central Bank (2022), ‘The economics of central bank digital currency’, Working Paper Series No 2713, August, section 3.2.

23 See, for example, European Central Bank (2022), ‘The economics of central bank digital currency’, Working Paper Series No 2713, August.

24 European Central Bank (2023), ‘Progress on the investigation phase of a digital euro – third report’, p. 1.

25 For example, see Brunnermeier, M. and Landau, J.-P. (2022), ‘The digital euro: policy implications and perspectives’, study requested by the ECON committee, January. European Central Bank (2022), ‘Tiered CBDC and the financial system’, Working Paper Series No 2351, January.

26 In a 2022 speech, Fabio Panetta of the ECB noted that: ‘We do not want to be “too successful” and crowd out private payment solutions and financial intermediation. But the digital euro should be “successful enough” and generate sufficient demand by adding value for users’. See European Central Bank (2022), ‘A digital euro that serves the needs of the public: striking the right balance’, March. Some authors question the assumption that caps on digital euro holdings would be necessary in the interest of financial stability. For example, see Hofmann, C. (2023), ‘Digital Euro: An assessment of the first two progress reports – the case for unlimited holdings of digital euros’, requested by the ECON committee, Economic Governance and EMU scrutiny Unit.

27 Reserve Bank of Australia (2020), ‘Retail Central Bank Digital Currency: Design Considerations, Rationales and Implications’, September, pp. 8–10.

28 Mastercard (2021), ‘Mastercard and Island Pay launch world’s first central bank digital currency-linked card’, February.

29 An ECB report notes: ‘A digital euro scheme appears to be the best option for ensuring that everyone in the euro area could pay and be paid in digital euro and for achieving the objectives of a digital euro […] To this end, a digital euro scheme would establish a set of common rules, standards and procedures that would need to be adhered to by supervised intermediaries in distributing the digital euro and that would ensure a balance between the respective roles and responsibilities of the Eurosystem and supervised intermediaries.’ See European Central Bank (2023), ‘Progress on the investigation phase of a digital euro – second report’.

30 Federal Reserve (2021), ‘CBDC: A Solution in Search of a Problem?’, speech by Governor Christopher J. Waller, 5 August. See also Angeloni, I. (2023), ‘Digital Euro: When in doubt, abstain (but be prepared)’, prepared by the Economic Governance and EMU scrutiny Unit at the request of the ECON Committee.

Related

Economics of the Data Act: part 1

As electronic sensors, processing power and storage have become cheaper, a growing number of connected IoT (internet of things) devices are collecting and processing data in our homes and businesses. The purpose of the EU’s Data Act is to define the rights to access and use data generated by… Read More

Adding value with a portfolio approach to funding reduction

Budgets for capital projects are coming under pressure as funding is not being maintained in real price terms. The response from portfolio managers has been to cancel or postpone future projects or slow the pace of ongoing projects. If this is undertaken on an individual project level, it could lead… Read More