Brexit: implications for the transport sector

Oxera’s independent review of the potential effects of Brexit on transport looked at its effects on the aviation, ports and rail sectors.

Market liberalisation

EU legislation provides a framework for market liberalisation across a number of sectors including aviation, rail and energy. While, in many cases, the UK is already compliant with many of the EU’s market liberalisation initiatives, Brexit would still have an impact due to changes in the way that UK businesses could interact with EU markets. Taking aviation as a case study, if the UK were to leave the single aviation market under Brexit, we would expect significant impacts on the way that airlines and airports can operate.1

Operations of (UK and EU) airlines

Currently, the single aviation market allows UK airlines certain freedoms not enjoyed by countries outside this market. These freedoms are:

- the right to fly between EU countries;

- the right to fly within an EU country (known as ‘cabotage’).

Brexit would remove these freedoms unless an agreement could be negotiated in the same way as Norway has done. (Norway is party to the agreement despite being outside the EU.) The new agreement would need to be in place before the UK leaves the EU (currently two years after a ‘Leave’ vote in the forthcoming referendum).

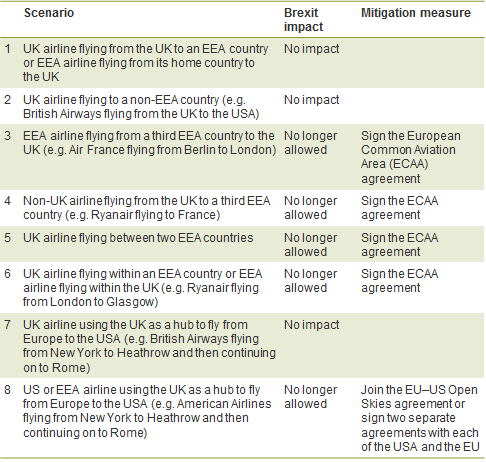

The restriction in the first freedom would have an immediate impact on UK airlines using EU airspace. Furthermore, it would not be possible to fly between the UK and a member state if the airline is based in a third member state. In other words, a German airline would not be able to service the routes between the UK and any EU country besides Germany (see rows 3 and 4 in Table 1 below). This in turn would significantly restrict competition and air traffic from the UK.

For the same reason, the restriction of cabotage would mean that fewer airlines could serve the UK domestic market (see row 6 of the table below). While the impact on domestic flights might be relatively small, the restrictions on the UK–EU market could be significant, restricting competition and driving up airfares.

Market liberalisation reform such as that put in place in the EU has had major impacts on the aviation sector. Estimates suggest that traffic growth following market liberalisation averages between 12% and 25%.2 For the single market in the EU, traffic growth doubled in the four years after liberalisation compared with the four years before it,3 and a report on the post-liberalisation market by the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) suggested that there were significant competitive benefits, such as declines in the market share of national carriers in both international and domestic flights.4

These flight restrictions would also affect UK airports. Under the EU–US Open Skies agreement, a US airline can operate flights between two points in the EU. Absent such an agreement with the UK, traffic from US airlines could be diverted to other hub airports such as Dublin.

More broadly, the UK would need to renegotiate airline services agreements with the EU and other partners in order to allow market access. Any such agreement could take several years to implement, however. Indicatively, the Open Skies deal took four years of negotiation to finalise.5

If there were a gap in these agreements in the interim period, the reduction in capacity would push airfares up. Most immediately, there would be a reduction in operators able to fly from the UK to EU member states, as described above. This could be partially offset by UK airlines switching operations away from Europe. Oxera estimates that if all flights operated by third-country airlines were removed, airfares for UK passengers would rise by 15–30% depending on the amount of capacity reallocation.6

These restrictions cannot simply be overcome by airlines setting up subsidiaries in Europe, because ownership restrictions do not allow non-EU investors to own a controlling interest in an EU airline.

The impacts of Brexit under different scenarios and possible ways to mitigate them are summarised in the table below.

Table 1 Summary of Brexit impacts and mitigation measures under different scenarios

Source: Oxera

Trade

In addition to the sectors that have been subject to specific legislation under the EU, there is the wider freedom of trade in goods. The transport sector helps facilitate this trade, and hence changes to volumes and patterns of freight would be an important aspect to Brexit for the sector.

The maritime industry would be the most directly affected by this, given the importance of freight to the sector. Any changes in trading patterns would be especially relevant for UK ports, which themselves are responsible for handling around 90% of the UK’s trade.7 High-value freight is also transported in bellyhold on passenger flights. This type of freight would be affected by the changes to passenger services described in the section above.

Under Brexit, the UK would lose the ability to trade freely with EU member states, at least until and unless a free trade agreement is put in place, which would have the following implications. (Delays in negotiations could mean a significant period trading under World Trade Organization, WTO, agreements.)

- UK trade would be subject to tariffs and import duties. In the WTO scenario, trade between the UK and EU member states would take place under most-favoured nation tariffs. In 2014 the EU’s average tariff rate was 5.3%.8

- UK trade would be subject to customs clearance. There would also be an increase in administrative costs. According to the WTO, around 8% of the financial cost of importing goods by sea comes from customs clearance.9 The World Bank estimates that the customs clearance process adds around a day to the import process for a single freight container. However, for multi-stop journeys through Europe, separate customs checks would be needed for each country a lorry had travelled through. Instead of a seamless journey off a ferry and onto a motorway, a lorry would have to wait while each separate pallet is checked, requiring extensive investment in parking facilities at UK ports and/or extensive queues in France (if customs clearance were moved there) or UK port towns.

Overall, World Bank estimates suggest that the additional customs requirements could add costs to trade. However, the scope of the impact is potentially more important. The EU is the UK’s largest trading partner. Some 49% of the UK’s trade in goods is with EU members.10 There is also evidence of a large increase in trade under EU membership. HM Treasury estimates show that EU membership increases trade with EU members by between 68% and 85% relative to a baseline position of WTO membership.11

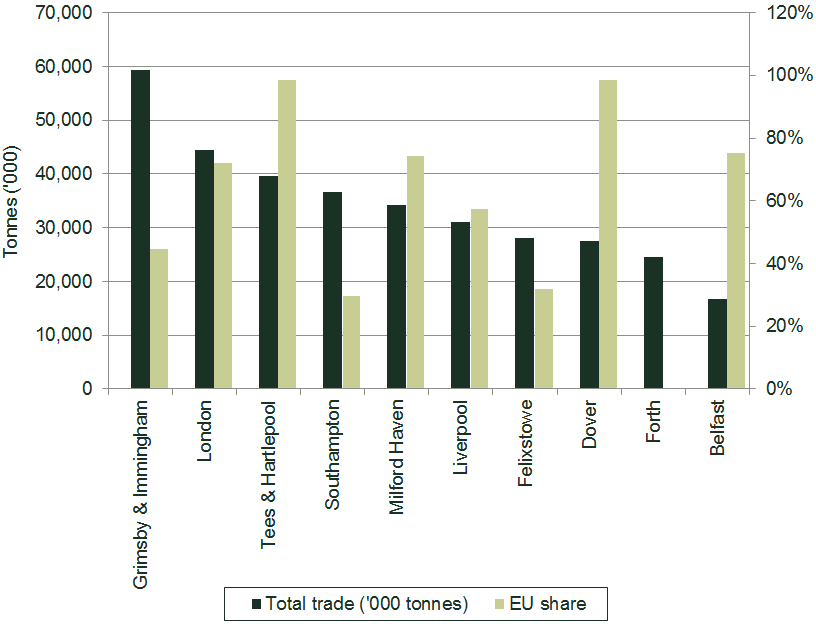

Also important is the distribution of impacts. Some ports are much more reliant on trade with EU member states than others. Figure 1 below shows the trade volumes handled by the ten largest ports in the UK and the share of EU goods. The data illustrates the considerable variation in the share of EU trade across ports, with Southampton and Felixstowe at around 30%, compared with virtually all traffic at Tees and Hartlepool.

Figure 1 Freight handled by top ten UK ports 2014

The impact on non-EU trade is less clear. While the relative cost of non-EU goods would decrease, membership also offers access to free trade agreements signed between the EU and third countries. Nonetheless, it is clear that Brexit under WTO rules would mean a larger reduction in trade patterns than an EEA scenario.

Removal of legislation

As we have described above, the EU has generally pursued a path of market liberalisation and facilitating competition. Removal of legislation from the EU could create possibilities for future policy changes that would otherwise appear contrary to this. One area on which the EU has legislated in particular is ‘unbundling’; the separation of network ownership and operation from use of the network. In transport, the rail sector is the most relevant example of this.

Until the mid-1990s, operations and management of tracks, trains and rolling stock was integrated under British Rail. Under current EU rules, this type of structure would not be possible. In particular, it would be necessary to establish functional and financial separation between tracks and trains. Brexit would offer the option for more varied models for the GB rail industry.

Core legislation on rail in the EU has been implemented in three ‘packages’. The forthcoming Fourth Railway Package proposes a number of measures, including rules on interoperability (which could occur irrespective of Brexit). Perhaps of more importance in this context are the proposed changes to the award of Public Service Obligations and to governance of the Infrastructure Manager, which specify rules for competitive tendering for rail service contracts, and independence of infrastructure managers. Both of these changes would mean that a return to the British Rail structure would be much more difficult.

In practice, most of the Directives are no stronger than regulations that would remain under the current GB industry model. However, the EU is moving towards a model to facilitate more on-track competition, which would make integration more difficult.

A reversion to the integrated British Rail model would require a concerted political effort too. Moreover, the evidence suggests that the changes to the industry model have resulted in benefits.12 However, this is not the only option for integrated rail models in Great Britain.

Following expiry of the current rail franchise agreement, the Welsh government is set to take control of the Wales and the Borders franchise, and Welsh Assembly Members have explored options for the future of the franchise, including public sector delivery of services. This would become easier under Brexit, if it were deemed preferable, while any reintegration of infrastructure and operations (e.g. to facilitate a South Wales Metro) would also be permissible.13

HS2 Ltd, the company responsible for delivery of the new rail line between London Euston, Birmingham and northern cities, is currently developing its plans on a ‘system’ basis. In other words, it is treating the new line as an integrated whole, which it will separate in due course as relevant legislation is firmed up. Under Brexit, there would be more options, including retaining the new infrastructure and operations as an integrated whole.14

Overall, any reintegration trials are likely to occur on a case-by-case basis, and would need strong economic evidence to support that approach, as opposed to preserving the current separated structure.

Indirect impacts

The UK leaving the EU would be expected to have indirect effects as well. In most cases, transport demand is driven by GDP, meaning that a decrease in GDP following Brexit would also reduce demand for transport services.

Scottish independence?

Further to this, Scottish ministers have raised the prospect of a second independence vote following Brexit. Since this would require a further significant decision, it is very much an indirect effect. However, the implications for the GB rail network and operators are significant.

There is already some segregation of services and network between Scotland and the rest of Great Britain. As with the rest of Great Britain, passenger rail services are predominantly provided through franchises. Scotland’s main internal rail franchise, the ScotRail franchise, is let and managed by Transport Scotland. As for the network itself, this is one of eight strategic routes managed by Network Rail. The route directors already have a wide range of financial and operational responsibilities, such as the operation, maintenance and renewal of track infrastructure.

However, full devolution would leave a number of issues to be resolved, many of which formed part of the debate surrounding the Scottish independence vote, although no firm plans were put in place.

Cross-border services—the main issue that could arise with Scottish independence relates to cross-border train operations. In 2013/14 there were around 8m cross-border journeys to and from Scotland,15 primarily on the East Coast and West Coast Mainlines, although Northern and TransPennine also run cross-border services.

Border control—operationally, cross-border franchises would in effect be running international services, which could require border controls.

Network Rail—despite devolution of powers to route directors, the current framework could be characterised as a ‘soft regionalisation’ with many key functions retained by the centre. It is unclear how Network Rail would operate under Scottish independence; however, there is a possibility of central functions needing to be relocated to a Scottish subsidiary, leading to increased cost.

Cross-border trade—any restrictions in cross-border trade will affect freight traffic and hence revenues for freight operators.

Given the uncertainty surrounding both whether this issue would become relevant following Brexit and the lack of clarity over how Scottish independence might work, this should be seen as a further source of uncertainty surrounding the outcome under Brexit.

Conclusion

Brexit would have wide-ranging implications for many parts of the transport sector and a number of forms that this could take have been examined here. In broad terms, the UK has well-developed institutions governing the transport sector, and market liberalisation is well developed compared with many other member states. Perhaps of greater importance is the market access that EU membership provides. This is relevant for the UK as a producer and UK residents as consumers, and is both direct (as we see in aviation) and indirect (as illustrated in maritime).

Oxera has undertaken an independent review of the likely impact of Brexit on different modes of transport.

Aviation: depending on how quickly aviation agreements could be re-established following Brexit, leaving the EU could restrict operations by UK airlines in Europe and by EU airlines in the UK. This could extend to US airlines (due to the UK exiting the EU–US Open Skies agreement). Our analysis suggests that such a restriction could lead UK passengers’ air fares to rise by 15–30%.

Ports: at present, over 90% of UK trade is handled by ports and the EU is the UK’s largest trading partner.1 Changes to the costs of trade with the EU are likely to affect the volumes and patterns of freight activity at ports, while the need for new customs checks on imports and exports is likely to cause considerable congestion at UK and mainland European ports. Any negative impact could be mitigated through EEA membership or free trade agreements, although delays in negotiations could mean a significant period trading under WTO agreements. The UK government has estimated that EU membership increases trade with EU members by between 68% and 85% relative to WTO membership.

Rail: removing EU legislation would enable a return to (or at least a trial of) having the same company providing tracks and trains. Currently, the EU’s rail Directives require separation of the two, and the forthcoming Fourth Railway Package will continue the process of separation. Indirect effects of Brexit could also have major implications for the transport sector. For example, Scottish ministers have raised the prospect of a second independence vote following Brexit. Scottish independence could have a significant impact on the operation, regulation and management of the network and train operators, particularly for the 8m cross-border journeys between England and Scotland each year.2

Note: 1 UK international port traffic as a share of total UK trade, based on Eurostat data and DfT port statistics. 2 Transport Scotland.

1 EEA countries are bound by the same aviation legislation as EU countries.

2 InterVISTAS (2006), ‘Economic Impact of Air Service Liberalisation’.

3 InterVISTAS (2006), ‘Economic Impact of Air Service Liberalisation’.

4 Civil Aviation Authority (1998), ‘The Single European Aviation Market: the first five years’, June.

5 EurActiv (2012), ‘EU-US “Open Skies” agreement’, 28 May, accessed 24 May 2016.

6 We assume that initial capacity reductions are met with higher load factors; with an increase of five percentage points occurring without a corresponding increase in price. Subsequent reductions in capacity result in increased fares.

7 UK international port traffic as a share of total UK trade, based on Eurostat data and Department for Transport (DfT) port statistics.

8 WTO statistics.

9 Defined by the WTO as document preparation, customs clearance, port and terminal handling, and inland transport/handling.

10 2014 Eurostat trade data.

11 HM Government (2016), ‘HM Treasury analysis: the long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives’, April.

12 See Oxera (2014), ‘What is the contribution of rail to the UK economy?’, July.

13 Options for governance of the metro system including a vertically integrated approach are explored in Lee, S., Carr, R. and Morgan, K. (2014), ‘Governing the Metro: Options for the Cardiff Capital Region’, School of Planning and Geography, Cardiff University, May.

14 See HS2 Ltd Development Agreement, para. 13.3, accessed 24 May 2016.

15 Transport Scotland.

Download

Related

Spatial planning: the good, the bad and the needy

Unbalanced regional development is a common economic concern. It arises from ‘clustering’ of companies and resources, compounded by higher benefit-to-cost ratios for infrastructure projects in well developed regions. Government efforts to redress this balance have had mixed success. Dr Rupert Booth, Senior Adviser, proposes a practical programme to develop… Read More

Is dynamic pricing an ambush or advantage for consumers?

The debate as to whether or when dynamic pricing is fair and reasonable continues, and there are even calls for it be banned. Dynamic pricing has been in the news recently, with backlash from fans trying to secure a ticket to see Oasis in concert. You will have experienced dynamic… Read More