Behavioural economics and its impact on competition policy: a practical assessment

The rise of behavioural economics has caused much debate in academia and among policy-makers. A new study for the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets explores the implications for competition policy. Although there is no need for major rewrites of competition law and economics textbooks, behavioural economics will form an important part of the competition policy toolkit, and will be relevant in a small but significant number of competition cases.

Behavioural economics uses insights from psychology to explain the effects of cognitive and behavioural processes on consumer behaviour and market outcomes. It provides insights into individuals’ behaviour which go beyond the traditional ‘fully rational choice’ approach set out in many microeconomics textbooks (see box below).

The rise of behavioural economics has led to a debate about the relative merits of this and traditional economics, in both academia and various policy arenas, including competition policy. On the one hand, commentators have argued that i) traditional economic models can explain some of the phenomena associated with behavioural economics, and competition practitioners have always had some awareness of consumer biases; ii) behavioural economics has greater relevance where individual consumers, as opposed to companies, are concerned; and iii) adverse outcomes resulting from consumer biases are best dealt with under consumer protection rather than competition policy. On the other hand, there are certain market outcomes that can be better understood, or remedied, with reference to insights from the behavioural economics literature.

Implications for competition and market outcomes

The cognitive processes and consumer biases studied in behavioural economics have implications for how demand and supply interact, and the market outcomes. Product differentiation and complexity can affect consumer behaviour. Consumer biases may get in the way of a virtuous circle between demand and supply, and firms may be able to exploit these consumer biases.

In particular, pricing frames matter. Experimental studies show how pricing practices, such as drip pricing, sales offers and complex pricing, can be profitable strategies that may harm consumers. With drip pricing, consumers face a headline price up front; as they engage in the buying process, additional charges are ‘dripped through’ by the seller. The endowment effect and mental accounting play a role: having engaged in the buying process, people’s point of reference (the anchor) shifts and they feel that they already own the product, so they are more inclined to pay not to lose it. Likewise, experiments show that sellers may have an incentive to create multiple-attribute products and set higher prices in order to confuse buyers, rather than simplifying the information and competing on price to capture market share.

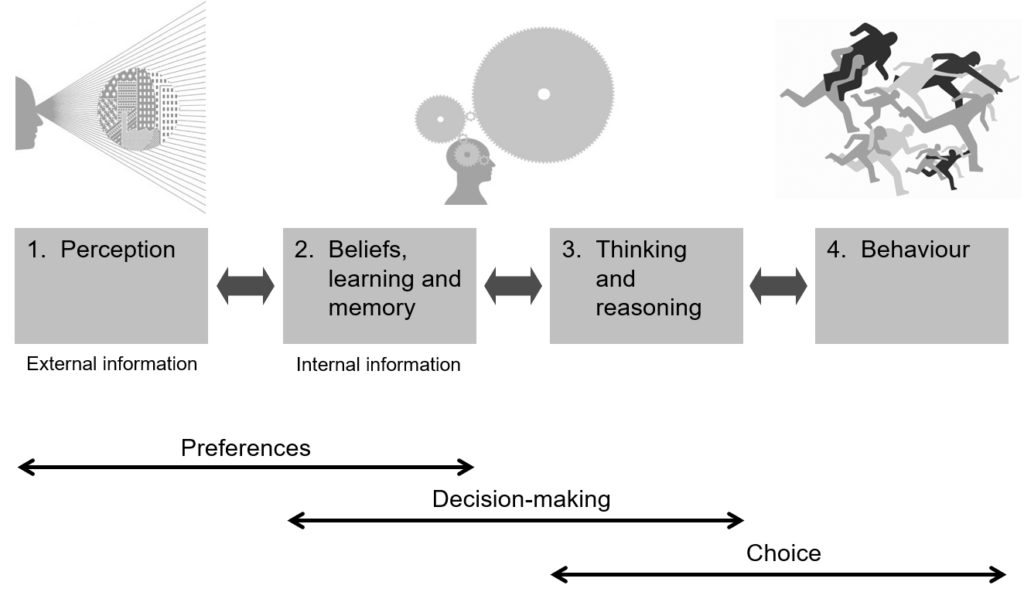

Cognitive and behavioural processes involved in consumer choices

The top half of the figure displays processes that will be familiar to psychologists: how people perceive information presented to them; how they draw on their internal information, such as beliefs, goals, and experience; how they then think about and weigh up the best course of action; and how they subsequently behave. The bottom half of the figure matches these to concepts that are familiar to economists: consumers’ preferences, their decision-making processes, and the choices they make in practice. Important insights from behavioural economics are as follows.

- Preferences depend on context. Preferences are reference-dependent, rather than driven by absolutes alone. For example, people dislike losing what they perceive they already own (their ‘endowment’) more than they like making gains. The prospect of a reward of €200 may be needed in order to outweigh the prospect of a penalty of €150. This is called ‘loss aversion’, or the ‘endowment effect’. Therefore, how information is presented, or framed, to consumers in terms of gains or losses can affect their preferences.

- Decision-making involves taking shortcuts. It would be exhausting to apply conscious, fully rational deliberation of every single choice to all day-to-day tasks. Instead, some decisions are made purely subconsciously and automatically, without much by way of thinking at all. Between conscious and subconscious decision-making lies a series of shortcuts known as ‘heuristics’, and these are not always accurate.

- Choices over time can be time-inconsistent. Consumers can face a conflict between their short-term urges and what would be best for them in the long term. In economics terminology, their preferences can be ‘present-biased’ or ‘time-inconsistent’.

One conclusion from the literature that has direct relevance for competition policy is that firms that engage in practices such as drip or complex pricing may have a greater and more persistent degree of market power than would follow from the traditional models of competition. Consumers may not exercise adequate discipline, and consumer learning may not be perfect. The presence of many naïve (as opposed to sophisticated) customers may exacerbate these adverse effects1 In the longer term, entry by new competitors may not always resolve the problem. There are market situations where even firms with small market shares have an ability and incentive to engage in these practices.

It is certainly not the case that competition policy intervention is called for in all these situations. First, the above situations are theoretical possibilities, and the severity of the adverse market outcome would have to be assessed empirically in each case. Second, intervention may not be appropriate or possible if the established market power thresholds in competition law are not met. (Market power is a matter of degree, and competition law concerns arise only if there is a significant degree of market power—in particular, dominance.)

Behavioural economics, market definition and market power

Insights from behavioural economics do not significantly change the tools used in competition investigations. The SSNIP test (small but significant non-transitory increase in price) remains an appropriate conceptual framework for defining the market in the presence of consumer biases. Conceptually, because the test is concerned with how consumers respond to price, and not why, it may often not really matter whether these responses are influenced by biases. Nevertheless, behavioural economics insights into why consumers behave in a certain way can help in framing a market definition analysis (e.g., when specifying the econometric model or survey to be carried out) and in interpreting and understanding its results.

It is well known that the choice of the price base to which a price increase is applied as part of the SSNIP test is crucial in obtaining a meaningful market definition. Behavioural economics suggests that this question is especially relevant where more than one price is involved—for example, with bundled products, add-ons or drip pricing. Furthermore, it may be relevant to consider price discrimination markets based on customer groupings that follow from the behavioural economics literature—in particular, the distinction between sophisticated and naive customers.

Applying the SSNIP test to markets with drip pricing or secondary products may reveal ‘pockets’ of market power: narrow markets, with market power/dominance for the provider. The case of payment protection insurance (PPI) is an example (see the box below).

The payment protection insurance case: a precedent for narrow markets?

PPI provides cover against events (e.g., unemployment, accident or illness) that may prevent consumers from keeping up with repayments on credit they have taken out. PPI is considered a secondary product because it is purchased only after the primary product (in this case, a credit facility) has been bought.

When the UK Competition Commission initiated its investigation into the market for PPI in 2007, PPI had developed into a popular retail insurance product, sold alongside personal loans, credit cards, overdraft facilities and mortgages.1 Mis-selling allegations in relation to PPI were investigated in parallel by the UK Financial Services Authority (FSA).2

From a competition perspective, problems arise with secondary products where consumers are deterred from shopping around for the product that is most appropriate for them. Although they may do so for the primary product, a failure to research the secondary product thoroughly may result in a lack of competition for this product. This can lead to poor quality or high prices— particularly if neither quality nor prices can be easily observed or understood by consumers prior to the purchase. This was the issue examined in the PPI case.

To define the relevant market, the Competition Commission addressed two questions.

- Does consumer behaviour in the market for the secondary product constrain the behaviour of providers? The Commission found that most lenders offered a PPI product only in combination with the credit product sold—in other words, it was not possible to obtain a loan from bank A and then purchase the PPI from bank B.

While a number of stand-alone PPI products had been launched, their sales volumes were relatively limited. Alternative insurance products were available, but evidence on competitive pressure from these products was mixed. One of the most important options available to consumers was, perhaps, simply not taking the PPI product—in other words, opting for no insurance. The Commission found that 60% of consumers who took personal loans and 80% of those who took credit cards did not purchase PPI.

- Does consumer behaviour in the market for the primary product constrain provider behaviour in the market for the secondary product? Consumer surveys undertaken by the Commission and by credit providers indicated that a significant proportion of consumers do, indeed, think about buying PPI before applying for a loan, and that some consumers look at various PPI products when shopping around for a loan. However, the Commission concluded that the number of consumers actually comparing in detail the costs of combined credit and PPI products was insufficient to place genuine competitive pressure on PPI providers.

The Commission therefore concluded that the relevant product market was an individual distributor’s, or intermediary’s, sales of a particular type of PPI policy. In other words, each distributor held an effective monopoly over the sale of PPI to its own credit customers. Whether this case serves (or should serve) as a precedent for narrow market definitions in competition investigations into this type of market remains an open question.

Note: 1 Competition Commission (2009), ‘Market Investigation into Payment Protection Insurance’, January 29th. Competition Commission (2010), ‘Payment Protection Insurance Market Investigation: Remittal of the Point-of-Sale Prohibition Remedy by the Competition Appeal Tribunal’, Final report, October 14th.

2 The FSA began investigating the market for PPI in 2005. See Financial Services Authority (2005), ‘The Sale of Payment Protection Insurance—Results of Thematic Work’, November; and (2009), ‘Update on FSA Work on PPI’, press release, FSA/PN/012/2009, January 20th. In April 2013, the FSA was replaced by the Financial Conduct Authority and the Prudential Regulation Authority.

This makes the abuse of dominance rules a potentially relevant instrument to intervene in such markets. However, as there is little precedence for this, significant caution should be exercised in such circumstances as there may be a risk of over-intervention.

Behavioural economics and the assessment of conduct and of mergers

Behavioural economics has a great deal of insight to add in relation to the effects of particular business practices on consumers and on competition. This is why it can be of relevance to the effects-based approach to abuse of dominance and restrictive agreement cases.

Abuse cases involving the direct exploitation of customers are rare, and usually limited to excessive pricing cases (as opposed to other exploitative practices, such as reducing service quality). Behavioural economics indicates that firms may sometimes have a greater ability to exploit their customers (or, more specifically, exploit consumer biases) than would follow from traditional models. Whether this means that competition authorities should look more closely at exploitative abuse cases, or leave it to consumer protection and financial regulation policies, is a question for further debate.

As regards tying and bundling,2 behavioural economics shows that consumer biases may reduce competition within a particular market or between markets, giving additional credence to the notion that a company can lever market power from a market in which it is dominant into one in which it faces competition. Whether such competition concerns can be dealt with under the rules on abuse of dominance is less clear. First, a dominant position must be established. Second, there is little precedent on such cases under the abuse of dominance provisions.

Restrictive agreements (horizontal and vertical) and mergers can be largely assessed using traditional approaches. However, a number of useful insights from the behavioural economics literature on both consumer and firm biases could be used to supplement these traditional approaches.

Behavioural economics and the empirical techniques used in competition investigations

Behavioural economics has provided some useful additions to the toolbox of empirical techniques used in competition investigations.

- For econometric analysis of revealed preferences, insights into consumer behaviour can help to identify which variables to include in the model, and how to interpret the results

- Behavioural economics sheds significant light on how surveys for market definition and merger analysis can be designed to obtain reliable information on stated preferences. Insights from psychology and from the behavioural economics literature have already helped in developing guidance on best practice in the use of surveys.3

- There is potential to make use of experiments in competition investigations, a tool frequently used in the behavioural economics literature that can add to results obtained from econometric and survey analysis. This is a relatively unexplored area.

Behavioural economics and remedy design

As noted above, remedies based on insights from behavioural economics can be used in cases dealing directly with market outcomes and competition concerns resulting from consumer biases, but they can also be used more broadly in cases where the competition problems are not related mainly to consumer biases as such.

An important implication of behavioural economics for remedy design is that policy-makers need to understand better the demand side of markets, in terms of how consumers actually behave. Collecting empirical evidence and testing the remedies are key steps in the process.

Behavioural economics points to smarter and more targeted remedies that deal effectively with behavioural biases by seeking to correct these or by finding ways of working with consumers’ biases to deliver a better course of action (rather than trying to resolve them). Such remedies may be liberal-paternalist in nature, which does not deprive consumers of choice, and which results in a better deal for affected customers without making matters worse for other consumers. Such policies might include:

- reducing information disclosure to the salient points, to overcome framing, information overload, and inertia;

- activating consumers to make a choice—the ‘forced choice’—as opposed to letting them remain inert or simply opt for the default;

- using default opt-ins or opt-outs—where there is a superior outcome for consumers, the policy might be to set that outcome as the default, without restricting consumers’ ability to choose an alternative.

These interventions tend to come at a lower cost than more heavy-handed interventions (such as subsidies or education programmes). Another advantage is that they retain the freedom for consumers to choose, but alter the frame within which they access information and make choices. If such interventions do not work effectively, there should not be too many unintended negative consequences.

Interventions may also be aimed at preserving consumer sovereignty. This accommodates the possibility that some consumers (eg, sophisticated ones) may be worse off as a consequence of the intervention, but that, in cost–benefit terms, consumers as a group are better off. It also means that not all interventions involve simple nudges, but instead that there may be bans on certain forms of conduct by companies in circumstances where there is a clear detriment to consumers. A risk with these more restrictive interventions is that there can be a fine line between liberal paternalism and straight paternalism.

Competition policy versus consumer protection and financial regulation

Competition law—covering rules on restrictive agreements, abuse of dominance and mergers—is perhaps not the most direct policy instrument for addressing adverse outcomes resulting from consumer biases. In order for an authority to intervene under competition law, there must be an anti-competitive conduct, agreement or merger. This necessarily limits the extent to which these competition law instruments can be used, since there will not always be such triggers for intervention in markets with problematic outcomes.

Consumer protection and financial regulation may allow for more direct intervention. Indeed, much of the behavioural economics literature on drip pricing and other themes seems to have been written with consumer policy interventions in mind, rather than competition policy as such. There is also a question as to whether behavioural economics, and the state of the empirical evidence base to date, provides sufficiently robust conclusions to give the legal certainty required in cases where anti-competitive behaviour is alleged.

An instrument that allows features of competition policy and consumer protection to be combined—and which may therefore be better suited to these cases than the abuse of dominance provisions—is the market investigation instrument under the UK Enterprise Act 2002.4 These investigations can be used to intervene in markets where competition appears to be ineffective, but where there is no obvious abuse of dominance or restrictive agreement. Remedies can be imposed on a forward-looking basis to address adverse competition outcomes, including those arising from consumer biases. Other jurisdictions may wish to consider adopting such a regime, or seek other policy options to combine features of competition policy and consumer protection.

Conclusions

Behavioural economics is unlikely to have a radical impact on competition policy. Indeed, if one were to write, or update, a textbook on competition law and economics, most of the text would probably remain unaffected by behavioural economics. It is likely that, in many competition cases, the insights from behavioural economics will not play a significant role, either because the cases concern business-to-business disputes where consumer biases are of less importance5 or because the traditional competition policy tools can account sufficiently for the effects of any consumer biases.

Instead, behavioural economics can be seen as providing useful additional insight. There are certain market situations and outcomes that are driven by consumer biases, and that can be understood or explained through behavioural economics. Phenomena such as search costs, switching costs and product differentiation have long been understood in the literature on industrial organisation (IO) and in competition policy. The added value of behavioural economics is that it can cast further light on what drives search and switching costs, and on how product differentiation affects consumer behaviour, in each of the access, assess and act stages of the consumer decision-making process (where consumer choice depends on the ability and inclination to search, compare products, and seek out better deals). Behavioural economics can then shed light on how firms might be able to exploit consumer biases.

In many conduct and merger cases in consumer markets, it may be useful to consider whether there are any relevant behavioural economics aspects, not as the sole approach, but rather as part of the broader economic toolkit with which a case can be analysed (which also draws on the fields of IO, financial economics, and econometrics). One cannot really classify competition investigations according to whether behavioural economics is relevant; sometimes consumer biases and bounded rationality will be a major factor in the investigation and at other times they will be just one aspect among others that need to be considered.

This article is based on a systematic review of the implications of behavioural economics for the instruments and tools used in competition law, undertaken for the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM). See Oxera (2013), ‘Behavioural Economics and its Impact on Competition Policy: A Practical Assessment with Illustrative Examples from Financial Services’, May. The ACM came into existence in April 2013 following the merger of the Dutch competition authority, the telecoms and postal regulator and the consumer authority. The report and this article do not reflect the views of the ACM.

1 Naive consumers are unable to learn or compare prices, which affects their purchasing and searching behaviour. By contrast, ‘sophisticated’ consumers are well-informed and purchase from the firm offering the lowest price.

2 Tying is when, in order to buy product A, a consumer is forced to buy product B as well. Bundling is when products A and B are (sometimes exclusively) sold together, usually at a lower combined price.

3 Office of Fair Trading and Competition Commission (2011), ‘Good Practice in the Design and Presentation of Consumer Survey Evidence in Merger Enquiries’, March.

4 The new Financial Conduct Authority in the UK also has powers to carry out competition investigations (outside the standard rules on agreements, abuse and mergers). The market investigation provisions of the Enterprise Act 2002 were recently amended through the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013.

5 As noted in the Oxera report, the literature on firm biases is at present insufficiently developed to guide competition policy. The focus of the report is on consumer biases.

Download

Related

Ofgem’s RIIO-3 Sector Specific Methodology Decision

On 18 July 2024, Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Decision (SSMD) for the forthcoming RIIO-3 price control period for electricity transmission (ET), gas transmission (GT) and gas distribution (GD) networks.1 This follows Ofgem’s consultation on the matter in December 2023.2 RIIO-3 will last for… Read More

The future funding of the England & Wales water sector: Ofwat’s draft determinations

On Thursday 11 July, Ofwat (the England and Wales water regulator) published its much anticipated Draft Determinations (DDs). As part of the PR24 price review, this sets out its provisional assessment of allowed revenues and performance targets for AMP8 (2025–30)—and will be of great interest to water companies, investors,… Read More