Assessing the profitability of motorway concessions in France

France’s ecological transition demands the modernisation of motorway infrastructure to support electrification, reduce emissions, and align with new mobility trends. As current concession contracts approach expiration, public authorities must establish a framework that achieves ecological goals while optimising public resources. The concession model, which entrusts private entities with managing infrastructure, can attract investment if risks and incentives are properly balanced. However, motorway concessions in France have faced criticism for perceived excessive profits. Assessing the profitability of past concessions could provide a relevant basis to guide the structuring of future contracts, including toll levels, duration, profit-sharing mechanisms, and decarbonisation incentives. This evaluation, however, must be approached with caution, as different indicators can yield varying conclusions about the profitability of current concession contracts.

Introduction

France has a long-standing tradition of developing infrastructure through concession contracts. An early notable example is the Canal du Midi, connecting the Atlantic to the Mediterranean, which was designed and built by Pierre-Paul Riquet between 1667 and 1681. In return for the construction and operation of the canal, King Louis XIV granted Riquet and his family the right to collect tolls, hunt and fish in the canal’s vicinity, and other benefits such as tax exemptions.

Three centuries later, a similar concession model—except for hunting and fishing rights—facilitated the development of France’s motorway network, with the first concession contracts signed in the 1950s. This model allowed companies, initially state-owned, to finance, construct, and operate French motorways. Concession contracts typically span several decades, ensuring a stable framework for investment and maintenance of what would eventually become France’s extensive motorway network.

Between 2001 and 2005, a significant shift occurred when the French government gradually privatised several motorway companies, transferring long-term concession rights to private operators. These concessions are set to expire shortly, starting from 2031, sparking debate around the most suitable model for motorways management in the future.

In particular, the French debate frequently centres on concerns about the high profit margins of companies in charge of operating motorways and their perceived excessive profitability.1 However, such concerns often overlook key factors that differentiate the concession model from more traditional industrial companies, and these have important implications for how the profitability of concession contracts should be assessed.

The profitability of a concession should be assessed over an extended period

Unlike other economic activities, a concession typically involves a large initial investment, with (motorway) concession companies earning their returns later through toll collection over the concession’s lifetime. This means that the profitability of a concession must be assessed over an extended period. Focusing on the profitability of the concession on any given year would not be meaningful from an economic perspective, as yearly profitability could vary greatly depending on whether it is assessed at the beginning or at the end of the concession contract.

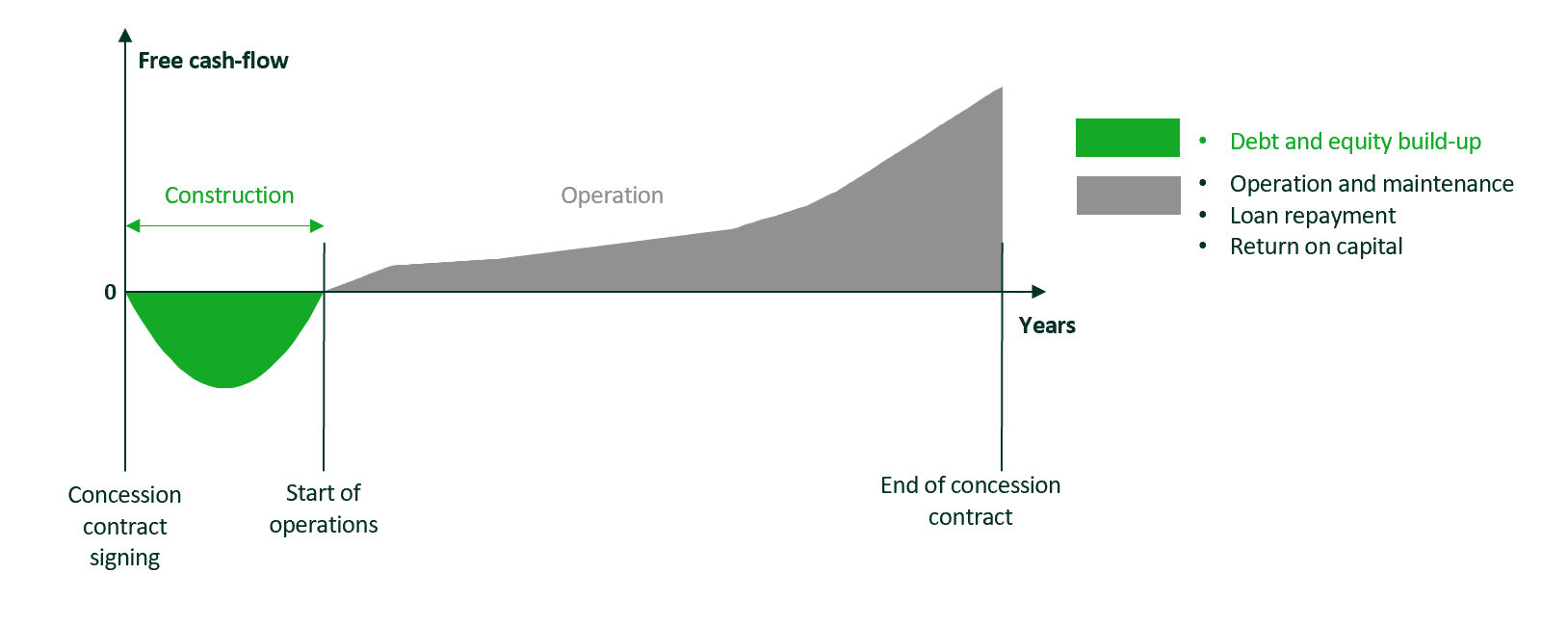

Figure 1 below illustrates a typical cash-flow schedule under a concession model, consisting of:

- a construction phase, marked by substantial investment outflows as debt and equity are deployed to finance the construction and development of the motorway infrastructure;

- an operational phase, during which cash flows gradually increase to meet operational and maintenance expenses, repay debt holders, and generate return on capital to shareholders.

Figure 1 Typical cash-flow schedule under a concession model

The figure presented above remains theoretical, as motorway concession companies typically carry out investment plans throughout the operational phase—for example, to expand the network, build new service areas and interchanges, or, more recently, to convert certain motorway sections to free-flow traffic.

Assessing the profitability of an investment over several years is generally performed by calculating an internal rate of return (IRR). The IRR measures the profitability of an investment based on the cash flows it generates over a specified period of time, making it a sensible metric for capturing the long-term nature of concession contracts.

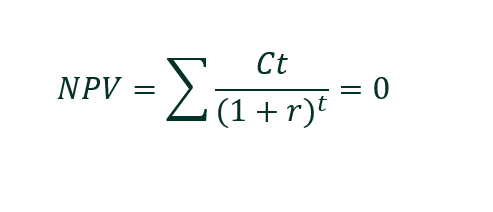

In more technical terms, the IRR represents the discount rate at which the net present value (NPV) of all cash flows (both inflows and outflows) of an investment equals zero. In simpler terms, it is the discount rate at which an investment breaks even, i.e. when the present value of the project’s cash flows is exactly equal to the initial investment.

Mathematically, the IRR is the rate r that satisfies the following equation:

Where:

- Ct is the cash-flow at time t;

- r is the IRR;

- t is the time period over which the IRR is measured.

This IRR framework can be used to assess the profitability of French motorway concession contracts. Depending on the question being addressed, different IRRs can be computed, as explained below.

Various types of profitability can be assessed in the case of French motorway concessions

When assessing the profitability of French motorway concessions, it would be important to examine both past performances and future prospects.

Looking ahead, should the concession model be renewed upon the expiry of current contracts, it will be crucial to design balanced contracts that ensure reasonable profitability for the concessionaire and fair toll rates for users. To achieve this objective, future contracts would need to be built on a projected IRR, calculated using various assumptions, such as traffic evolution and toll rates.

Looking to the past, it would be important to assess the profitability achieved by motorway management companies and to consider whether these levels could be regarded as ‘excessive’. This could determine whether the perception of ‘excessive profitability’ that sometimes prevails in the French debate can be considered legitimate. The final profitability of current contracts should be assessed at the end of the concession period using a realised IRR.

In addition to the prospective and historical aspects, it is possible, depending on the purpose of the analysis, to calculate different types of realised IRR. For instance, one might analyse the IRR of concession contracts as a whole to assess whether the key parameters underpinning these contracts were appropriately calibrated to cover the concessionaire’s capital and operating costs. Alternatively, the focus might be on assessing the IRR achieved by investors who acquired concession rights during the privatisation of French motorways, offering insights into whether these contracts were properly valued at the time of privatisation.

More generally, the realised IRRs that can be computed depend on the length of the investment period analysed (the profitability can be assessed over the entire lifespan of the concession contract or only for a portion of it) and the type of investors considered (the profitability can be assessed from the sole perspective of shareholders or from the perspective of both shareholders and lenders). The insights offered by each of these IRRs are detailed below.

Assessing profitability depending on the investment period considered

When looking at the IRR for a given French concession contract, one can focus on the IRR derived over the entire lifespan of the concession period or over only a portion of it.

Focusing on a portion of the concession helps to assess the concession’s profitability at key moments in its lifecycle, such as when an amendment to the concession contract is established. For example, in the case of French motorway concessions, a recurring question in the debate is whether the concession rights were appropriately valued at the time of privatisation. This question can be answered by computing the IRR derived by the investors who acquired motorway concession rights at the time of the privatisation of French motorways, resulting in an IRR for the privatisation. In this context, a high IRR could suggest that concession contracts were undervalued by the French State at the time of privatisation, or that concessionaires proved highly effective in outperforming the reasonable terms of the concession contracts.

Alternatively, one can focus on the entire concession period, which yields an IRR for the concession. This metric would provide an overall view of the contract’s financial balance, indicating whether the concession contract main parameters (including duration and toll rates) were appropriately set to cover the concessionaire’s capital and operating costs. This metric is particularly favoured by the French transport regulator (as detailed in the Box 1 below).

Assessing profitability depending on the type of investor considered

In evaluating the profitability of French motorway concessions, another critical question is whether profitability should be assessed from the perspective of all fund providers or solely from that of the shareholders. These two approaches offer distinct insights.

To focus on profitability taken from the perspective of all fund providers, one should assess the project IRR. This metric helps to determine whether the project’s key parameters (such as toll rates and duration) were set appropriately to cover all capital and operating costs and reasonably compensate fund providers (equity and debt). The project IRR is calculated using the cash flows available to both shareholders and lenders. This is the indicator favoured by the French transport regulator, along with the IRR for the concession (see Box 1 below).

Profitability taken solely from the perspective of the shareholders (or equity providers) is assessed using the shareholder IRR. Shareholders often boost their investment capabilities by borrowing debt from external sources. Since the cost of debt is typically lower than the cost of equity, this strategy enables shareholders to increase their returns without needing to invest more of their own capital, thereby enhancing their overall profitability.

As a result, the shareholder IRR is usually higher than the project IRR and is influenced by the financing strategy deployed by shareholders. In practical terms, in the case of French motorway concessions, this implies that the profitability achieved by shareholders may, to some extent, be driven by their financing strategy rather than solely by the concession contract parameters, such as toll rates and duration. Consequently, the IRR should be interpreted with care when assessing the profitability of concession projects.

Which IRR is of interest to the French transport regulator (ART) in the case of French motorway concessions?

In the case of French motorways, ART has indicated that it will focus on assessing the project IRR of concession contracts (measured over the entire lifespan of each concession), as the regulator is:

responsible for ensuring the smooth operation of the toll tariff system […] interpreted as the return on capital paid by the user through tolls. This return is to be understood as including all providers of funds and over the entire duration of the contract.

Source: Autorité de Régulation des Transports (2023), ‘Economie générale des concessions, Focus “La rentabilité des concessions”’, July.

Calculating an IRR in isolation provides limited insights. To draw meaningful conclusions, it is essential to compare it against an appropriate benchmark, as outlined below.

Profitability should be assessed in light of the cost of capital borne by motorway management companies

Once computed, it is important to compare the IRR against an appropriate benchmark to allow for the interpretation of its value—for instance, in the case of French motorway concessions, to determine whether the IRR could be considered ‘excessive’.

Profitability of motorway management companies is closely tied to the various risks that they undertake as part of the concession contract (such as traffic risk, operational risk, construction risk, and financing risk). Investors in motorway management companies expect a commensurate level of remuneration for assuming these risks.

Such risks are typically factored into the cost of capital incurred by motorway management companies. Given that investors usually expect an IRR greater than their cost of capital (they would otherwise allocate their funds to alternative investments), the cost of capital borne by motorway management companies provides a useful reference point in order to benchmark the IRR associated with investments in motorway concessions.

Therefore, in the case of current concession contracts, an IRR substantially higher than the cost of capital borne by motorway management companies may indicate that they have earned profits in excess of the costs of financing the infrastructure.

The reason for these potential additional returns may then be subject to further economic assessment: are they related to the concessionaire’s efficient operation of the motorway, or are they related to factors outside their control? For instance, one could argue that motorway concession companies have benefitted from a low-interest-rate environment, which facilitated debt refinancing and enhanced shareholder returns.

Concluding remarks

As current French concession contracts approach expiration, it will be crucial to assess the profitability of those contracts and understand the drivers that might have contributed to any potential cases of higher-than-anticipated profitability. This understanding will help inform the design of future contracts—if the concession model is to be extended—in order to appropriately compensate private investors for the risks that they assume while aligning returns with their cost of capital. Designing a suitable model for motorway management is particularly vital in light of the significant investment in motorway infrastructure that will be required in the coming years to reduce carbon emissions in transport, including the development of shared mobility solutions, electric vehicle charging infrastructure, and the adaptation of motorways into renewable energy production sites.

Footnotes

1 See, for instance, Albert, C. (2023), ‘Bercy désarme face aux milliards d’euros de profits des sociétés d’autoroutes’, 22 March, Le Monde.

Related

The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say? (Part 2 of 2)

On Thursday 23 October in Brussels, Oxera hosted a roundtable discussion entitled ‘The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say?’. In the second of a two-part series, we share insights from this productive debate. The discussion took place in the context of an… Read More

The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say? (Part 1 of 2)

On Thursday 23 October in Brussels, Oxera hosted a roundtable discussion entitled ‘The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say?’. In the first of a two-part series, we share insights from this productive debate. The discussion took place in the context of an… Read More