The failing-firm defence: a ‘get out of jail free’ card in mergers?

The failing-firm defence provides a way to clear mergers in cases that would otherwise be characterised by significant anticompetitive effects. It requires a structured and rigorous economic approach. What are the lessons from recent UK and European clearance decisions that have relied on this defence?

The failing-firm defence (sometimes termed the ‘exiting firm scenario’) is an important argument in some merger cases. The essence of the defence is that if at least one of the merging firms would have failed if the merger had not gone ahead, there can be no loss of competition as a result of the merger.

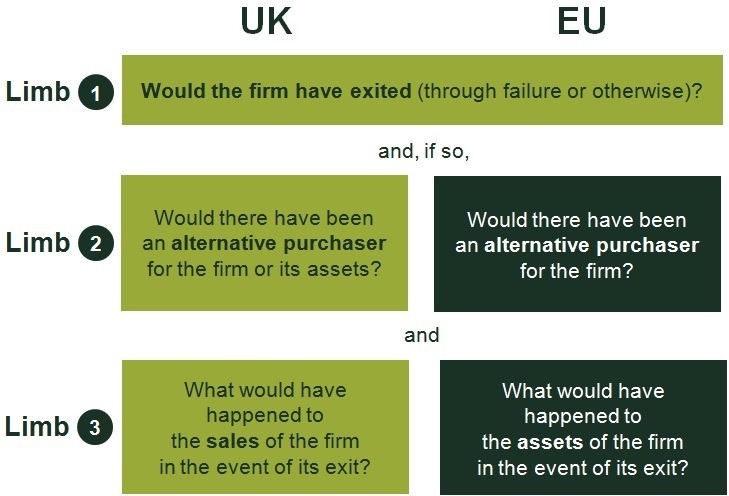

A successful failing-firm defence requires it to be shown that the counterfactual world without the merger would not be substantially less anticompetitive than the world where the merger does take place. The various competition regimes apply a similar three-limbed test, which assesses the inevitability of exit of the relevant firm (limb 1), the lack of an alternative purchaser for the failing firm or its assets (limb 2), and whether the merger leads to a substantially less anticompetitive outcome than the exit of the firm (limb 3). The defence is passed only if all three limbs are satisfied.

Although the test may seem straightforward, it is not easy to satisfy, which may explain why there are few recent examples of this defence being used successfully. Some recent high-profile cases are detailed in the box.

The test

Figure 1 shows the three steps of the failing-firm defence test.

Figure 1 The steps of the failing-firm defence test

Source: Competition Commission and Office of Fair Trading (2010), ‘Merger Assessment Guidelines’, CC2 (Revised), September; and European Commission (2004), ‘Horizontal merger guidelines’, OJ C31, 5 February.

Limb 1

The essence of limb 1 is to demonstrate that the exit of the firm being acquired (or the ‘target’) was indeed inevitable. It should be the case that the acquired party was unable to undertake any restructuring programme that would allow it to return to profitability, and that it was unable to secure the necessary additional funding that would help it to survive. The critical element here is for the merging parties to be able to provide sufficient evidence—for example, in the form of investor presentations, board and other internal documents, and any other materials—that confirms the severe financial difficulties of the target, and any failed attempts by its management to restructure or otherwise rescue it. This can often be difficult since a failing firm will often want to paint a positive picture of its financial position to attract potential buyers.

Limb 2

The second limb of the test requires the merging parties to demonstrate that there are no alternative buyers, or that an acquisition by any other buyer would not lead to a substantially less anticompetitive outcome than one brought about by the proposed merger. Potential alternative purchasers may fall into two broad groups: non-trade buyers (i.e. firms from other industries), and trade buyers. It is in the latter case that anticompetitive effects of the purchase would typically need to be assessed.[1]

The timing of such an alternative purchase is also crucial—if another buyer expressed interest but, for example, required additional time to conduct due diligence, the failing firm might actually have failed in the meantime. The value of the firm can change substantially depending on whether it is a going concern, has gone into administration, or is already being liquidated. Individual assets will also be affected to differing extents, and while tangible assets such as shops and factories will be relatively unaffected, intangible assets such as the firm’s brand may suffer significantly. Depending on the industry concerned, the timing of the transaction and readiness of alternative purchasers require careful consideration.

In this respect, although the merging parties will be aware of the official statements of the potential alternative buyers, competition authorities may contact these buyers directly to understand their intentions. While a majority of the evidence required for the merger filing can be prepared, forming a clear view of potential alternative purchases and their likely intentions consistently proves to be a difficult area where many failing-firm defences fail.[2]

Limb 3

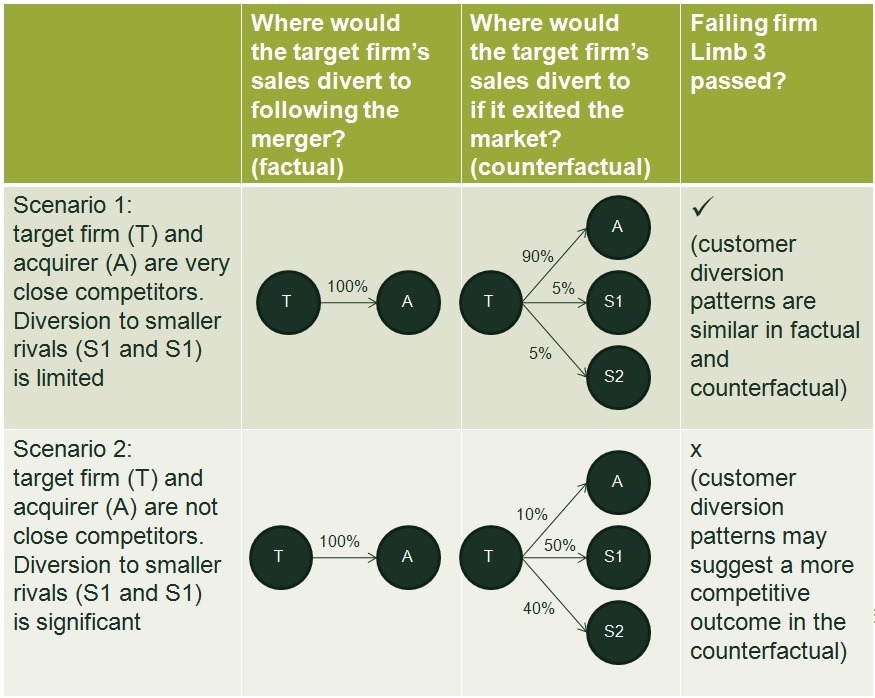

The last limb of the failing-firm test in the UK regime assesses what would have happened to the sales of the failing firm in the event of its exit from the market. In particular, it is necessary to show that the acquisition would not be substantially more anticompetitive than any natural diversion of customers to rival firms that would occur after exit of the failed firm. This analysis would therefore require an assessment of the likely behaviour of the failing firm’s existing customer base—for example, via diversion ratios (i.e. the extent to which customers would switch to the remaining industry participants). It is also important to consider the impact on the market as a whole—for example, the loss of one supplier could, through a change in reputation and other effects, lead to an overall market shrinkage.

The failing-firm defence could, in fact, be at odds with unilateral effects analysis (which is typically undertaken to measure the loss of competition between merging parties: the higher the diversion ratios between them, the more they compete pre-merger and therefore the higher the loss from the merger). For a successful argument under limb 3 of the failing-firm defence, a high diversion ratio to the acquiring party is desirable since it indicates that, if the failing firm exits the market, its customers (sales) would naturally divert to the acquiring party. Since this is the same outcome as that after the merger, the merger itself does not lead to a significantly less anticompetitive outcome than the firm’s failure.

If, however, this is indeed the case (i.e. the diversion ratio is high), and the failing-firm defence is not accepted (for example, because of failure of limb 2), the evidence would suggest that the merger would lead to a direct reduction in the level of market competition, thus raising unilateral effects concerns. This is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Limb 3 of the failing-firm defence

Source: Oxera analysis.

A recent example: the Optimax/Ultralase merger

The Optimax/Ultralase merger is the most recent example of a successful application of the failing-firm defence in the UK. Optimax acquired Ultralase in November 2012, and notified the transaction to the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) in December 2012. The OFT referred the case to the Competition Commission in July 2013, and Phase 2 was completed with an unconditional clearance in November 2013.[3] In April 2014, the OFT and Competition Commission were merged to form the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA).

Brief market overview

Optimax and Ultralase operated in the UK refractive eye surgery market, which spans two types of procedure:

- laser eye surgery, which is a vision-correction procedure that requires a laser and a trained optometrist, but not a full operating theatre;

- intraocular lens treatment, which replaces or adds a lens, and requires a full operating theatre with associated staff.

The merging parties were the second- and third-largest companies in the market, with Optical Express as the market leader with a national presence, and Optegra and Accuvision being other notable providers.

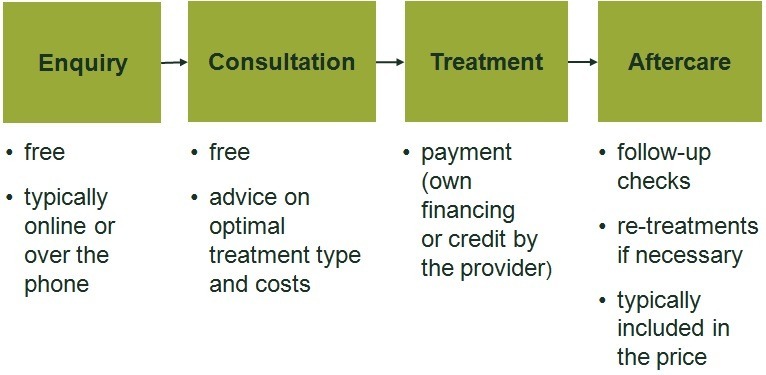

Customer journeys tend to follow a broadly similar path, from a free enquiry and consultation, through to treatment and aftercare. This is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Typical customer journey in refractive eye surgery

Source: Oxera analysis.

Refractive eye surgery is often considered a luxury purchase, and hence demand for such services fell considerably after the economic recession of 2008.[4] The drop in demand, coupled with the significant installed treatment capacity in the UK, means that many clinics have been under-utilised in recent years. Ultralase was one of the firms to be significantly affected by the fall in overall market demand, and the merging parties put forward the failing-firm argument in support of the acquisition.

The failing-firm defence test when applied to Optimax/Ultralase

All three steps of the failing-firm defence test were eventually passed in the Competition Commission’s Decision.

- Of the three limbs, limb 1 was passed by both the OFT and the Competition Commission. There was ample and clear evidence that Ultralase was expected to run into funding problems towards the end of 2012, and that its previous restructuring programmes had been unsuccessful.

- For limb 2, the sale process of Ultralase started in April/May 2012, and a number of potential buyers expressed interest in acquiring it. However, Ultralese received only one offer, from Optimax, and, faced with the prospect of going into administration, accepted this.[5] Oxera prepared a model for Optimax that modelled Ultralase’s likely future profitability in a range of general market and own operating performance scenarios. The results of the analysis showed that a private equity or other purchaser would not be able to achieve a sufficient return to justify the initial investment.

The OFT, in its Phase 1 assessment, found that it did not have enough evidence to conclude that there was no realistic prospect of a substantially less anticompetitive purchaser for Ultralase at the time of the transaction. In contrast, the Competition Commission, based on extensive discussions about the likely counterfactual with all parties involved in the sale process, concluded that that there was no credible alternative purchaser that would have acquired Ultralase as a going concern, or its assets on a piecemeal basis. - To assess limb 3, the Competition Commission carried out a consumer survey which found high diversion ratios from Ultralase to Optical Express (the largest player in the market) and to Optimax. As a result, it concluded that Ultralase’s exit would not have led to a substantially less anticompetitive outcome than the merger. Interestingly, although the OFT did not comment on this limb of the test (as limb 2 was not passed at Phase 1), it noted that there was a likelihood of significant unilateral effects in certain local areas where the merger led to a reduction from two to one, three to two, and four to three providers. This conclusion is in line with the Competition Commission’s finding with respect to the diversion ratios from Ultralase to Optical Express and Optimax.

Get out of jail free?

The failing-firm defence is not a straightforward argument to put to competition authorities. The second limb, in particular, often requires that the authorities obtain evidence from third parties. Having said this, merging parties can prepare a strong case by making sure that any evidence demonstrating inevitability of exit is robust, and that the process of marketing the failing firm is transparent to all potential acquirers (and investigation by the regulators).

1 Another alternative would be a piecemeal sale of the failing firm by multiple purchasers. Such a division of assets could be a more competitive market outcome (and thus invalidate limb 2 of the test), although it would be necessary to prove that the buyers were, indeed, willing to undertake a piecemeal purchase.

2 For example, the Competition Commission rejected Eurotunnel’s proposed acquisition of some of SeaFrance’s assets on the basis that there was an alternative and substantially less anticompetitive purchaser. See Competition Commission (2013), ‘Groupe Eurotunnel S.A. and SeaFrance S.A. merger inquiry’, para. 5.27. American Greetings’ acquisition of Clinton Cards was allowed to go through, despite the failing-firm defence being rejected owing to doubts about the inevitability of exit, and the presence of an alternative purchaser. See Office of Fair Trading (2012), ‘Completed acquisition by American Greetings Corporation of Clinton Card Group’, para. 63. The main reason for this, however, was that there was no horizontal overlap between the merging parties, and the merged entity did not have the ability and incentive to foreclose downstream rivals. Similarly, customer foreclosure was not an issue.

3 Office of Fair Trading (2013), ‘Completed acquisition by Optimax Clinics (Unlimited) of Ultralase Limited’, case ME/5898/13, reference made on 29 July, full text published 6 September. Competition Commission (2013), ‘Optimax Clinics Limited and Ultralase Limited – a report on the completed acquisition by Optimax Clinics Limited of Ultralase Limited’, 20 November. Oxera advised the merging parties.

4 Replacement of a cloudy lens, which is categorised as a ‘cataract’ procedure rather than a medical procedure, can be performed on the NHS. The focus of the merging parties was on cosmetic procedures linked to vision enhancement.

5 The timing of the transaction was particularly relevant in this case. With a purchase as ‘delicate’ as eye surgery, customers tend to value the reputation of the provider. Any news of the provider going into administration would have been likely to have a significantly effect on the value of the Ultralase brand.

Download