Investment opportunities in the water sector

A new model (Direct Procurement for Consumers, DPC), and an extension of the Specified Infrastructure Project Regulations (SIPR), are being used as a means of introducing competition into the delivery of new infrastructure in the England and Wales water sector. The current major projects pipeline requires £50bn across 30 projects. Each project has whole-life expenditure of over £200m, and 27 of them will be tendered through DPC or SIPR. We build on Ofwat’s major projects guide for investors,1 providing additional analysis of Ofwat’s major projects and questioning some prevailing assumptions.

Introduction

The water sector has entered a period of significant growth in investment over multiple asset management periods (AMPs). According to companies’ long-term delivery strategy submissions, around £276bn of enhancement investment alone is anticipated from AMP8 through to AMP12.2 The Final Determinations for AMP8 allow for £45bn of enhancement investment across the sector.3 In addition, major projects with total whole-life costs close to £50bn have been identified for procurement during AMP8,4 with 90% under either the Direct Procurement for Consumers (DPC) or Specified Infrastructure Project Regulations (SIPR) models. Ofwat views the DPC route as the default option for a major project, and a case must be made for SIPR or in-house provision if the DPC route is not chosen.

While one project has already been delivered under SIPR—the Thames Tideway Tunnel—the DPC model is at an earlier stage of development, with just one project—United Utilities’ Haweswater Aqueduct Resilience Programme—approaching financial close. This article focuses on the newer DPC model and its role in delivering the pipeline of DPC projects. It begins with an overview (for more detail, please refer to the Ofwat guide for investors),5 before contrasting the DPC model with SIPR, and explaining the relevance of the Regulators’ Alliance for Progressing Infrastructure Development (RAPID) for strategic resource options (SROs). It then compares the aspirations for DPC and SIPR with the historical experience of actual schemes, and considers risks and obstacles for investors.

DPC overview

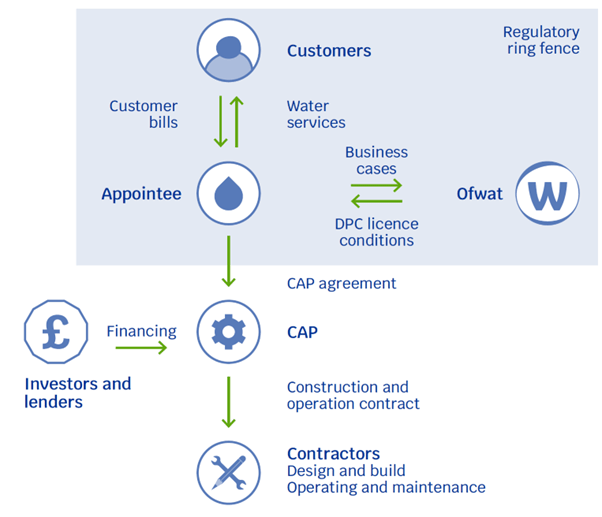

Figure 1 shows the key relationships between stakeholders, including the water company (the ‘Appointee’), the Competitively Appointed Provider (CAP) and its investors, and the supply chain.

Figure 1 Essential principles of DPC

Ofwat’s primary objective in developing DPC is to improve value to customers by increasing the level of competition in the design, build, financing and operation of major assets, which should control costs and allow savings to be passed on to customers.6 There is also the potential for increased innovation and for focused incentives on delivery and operating performance, backed by contractual commitments.

Access to new sources of equity capital is also an advantage that has emerged in the PR24 price review, given the pressure on company balance sheets from needing to finance a significant increase in expenditure. However, the water companies, while recognising these potential benefits and transferring some risk to the CAP, also have concerns about loss of control over the operation of a major asset on which their own operations and performance depend.7 Furthermore, the DPC process is lengthy and complex, even for apparently discrete assets, as protocols for construction, operations and maintenance must be developed.

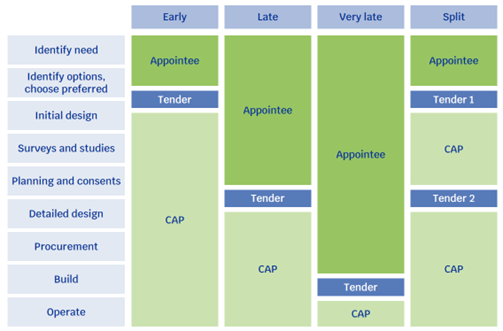

Further complexity is added by the variety of tender models that are available for DPC, and it rests with the water company to identity the best model for the project. Figure 2 summarises the options available, with tendering occurring at different stages in the project lifecycle. The degree of risk exposure to the CAP will differ markedly across models, as construction carries a higher risk than operations.

Whatever model is adopted, contract design is crucial, given historical experience. The PFI contracts that Scottish Water inherited when it was created in 2002 involved private companies building, refurbishing and operating 21 sewage plants across Scotland, with contract durations ranging from 25 to 40 years. The performance of these PFI sewage plants was problematic. Reports highlighted persistent mechanical failures, pollution, odour issues, and a general inability to meet certain performance standards. Scottish Water was forced to pay over £100m extra to address faults. Hopefully the lessons of the past have been learned.

Figure 2 Tender models for DPC

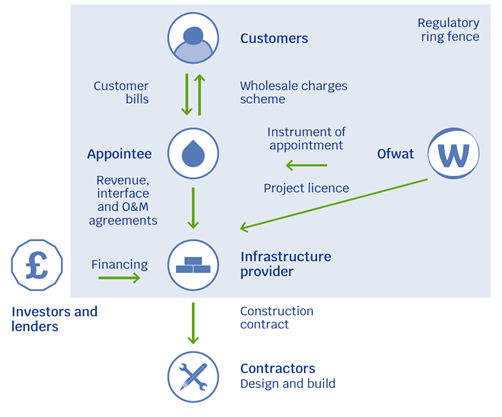

Comparison with SIPR

In March 2025, it was announced that the Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) will amend the existing rules on SIPR to streamline delivery of major water projects.8 This follows its successful use of SIPR for the completed Thames Tideway Tunnel project to lower the cost of capital (the weighted average cost of capital was only 2.497%, RPI-linked9—although this exceptionally low rate may reflect risk transfer to the customer away from the infrastructure provider, and may therefore not be evidence of the effectiveness of the procurement approach, as is often presented). Under SIPR, an Infrastructure Provider is granted a licence by Ofwat, which then regulates it directly, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Essential principles of SIPR

The differences between DPC and SIPR are presented in detail in Ofwat’s guide for investors (pp. 21 to 23).10 However, in summary, in order for SIPR to be used, the project must be of a size and complexity such that Ofwat considers that it would place at risk the water company’s ability to provide services to customers, and that SIPR would therefore provide better value for money. Size is crucial, as set-up costs for SIPR are higher, but the savings in cost of capital may be greater if the project is large enough, as SIPR has greater scope for transferring risk to customers and/or taxpayers.11 This arrangement lowers risk to the licensee when conditions are uncertain (under DPC, the CAP can seek to pass on risk only down the supply chain) and allows the investment to be viewed as an investment in a utility company, as opposed to project finance for a discrete project.

The water company may express a preference for SIPR over DPC and argue its case, but the decision ultimately rests with Ofwat. The analysis of the AMP8 projects presented below shows that Ofwat has already made a provisional decision on each.

Relationship to RAPID

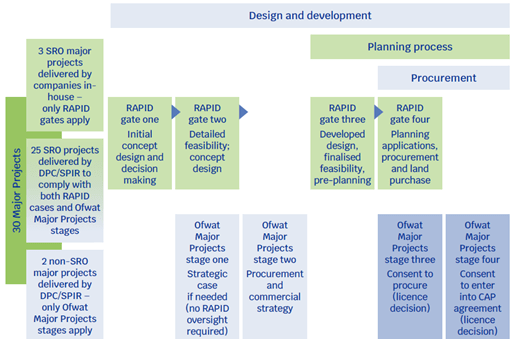

A related but separate initiative, set up in 2019, is the Regulators’ Alliance for Progressing Infrastructure Development (RAPID), which is a collaboration of the three England and Wales water regulatory bodies: Ofwat, the Environment Agency, and the Drinking Water Inspectorate. RAPID is focused on Strategic Resources Options (SROs); not all major projects are SROs, and three SROs will be delivered in house rather than by DPC or SIPR.

RAPID’s oversight rests on a four-stage gated process, which is shown in the figure below along with its relationship to Ofwat’s own four-stage gated process.12

Figure 4 RAPID and Ofwat’s gated processes

The effect of these gated processes is to reduce risk as they prevent a project proceeding prematurely and leading to subsequent cost and delay. Risk is discussed below in more detail.

Risk transfer under DPC

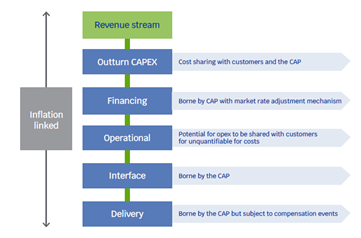

The issue of risk transfer is crucial, and although a water company may expect a transfer to the CAP, the CAP will need to be resilient to shocks. Figure 5 shows an overview of the expected risk transfer under DPC according to Ofwat. However, the actual risk transfer will depend on the CAP agreement.

Figure 5 Risk transfer under DPC

Further details on risk transfer are provided in the Commercial Framework section of Ofwat’s guidance on DPCs13 (for SIPR, a bespoke treatment of risk can then be built into the licence agreement).

Track record from PR19 (AMP7)

During the PR19 process, three projects were identified as candidates for DPC: United Utilities’ Haweswater Aqueduct Resilience Programme (HARP), Anglian Water’s Elsham Transfer and Treatment scheme, and Dŵr Cymru’s Cwm Taf Water Supply project.

HARP is the most advanced of these and has been dubbed a ‘pathfinder’ project. A preferred bidder has been identified; there will be a target cost contract, the contractor is reimbursed for costs, but the target cost is a key element, providing incentives for a sharing of risks and rewards between United Utilities and the CAP. If the project is delivered under budget, the CAP benefits; conversely, if the project exceeds the target cost, the CAP will absorb a portion of the overspend. There will also be oversight from Ofwat, which will have an independent consultant assessing the CAP’s management of project costs and delivery. The total contract duration will be 33 years from the point when the contract is awarded, and the CAP is obliged to provide the finance necessary to deliver the project. Work is currently underway on two key documents, one dealing with risk14 and the other dealing with charging mechanisms, via the Allowed Revenue Direction.15 Ofwat will not set prices but these will be set as the result of the tendering process, with the water company collecting the funds from customers and passing them on to the CAP.

Unfortunately, the other two DPC candidates have progressed less smoothly. The scope of Anglian’s Elsham scheme has been altered.16 It is now being delivered in house due to the potential for delay if the novel DPC approach is used, which would have implications for Anglian meeting its environmental obligations.

The Cwm Taf Water Supply project has also had its scope varied from that originally proposed in PR19, with a multi-site solution now proposed in PR24. The revised version will proceed as a DPC, with a contract award expected in 2026; the project is being delivered under the Mutual Investment Model agreement, reflecting the Design, Build, and Finance nature of the DPC approach.17 A fourth project, Portsmouth Water’s Havant Thicket reservoir, is being delivered in house but subject to a ten-year price control.

The progress of the AMP7 DPC candidates from PR19 has therefore not been straightforward, with only one, HARP, proceeding as planned.

AMP8 major projects pipeline

Ofwat has published a list of 30 major projects that are in the pipeline, grouped by company, with 27 to be delivered by DPC or SIPR.18 Table 1 presents an extract from that list, including only projects with a scheduled start date for construction of 2029 or earlier.

Table 1 Near-term major projects portfolio at Final Determinations (£m, 2022–23 prices)

Source: Ofwat (2025), ‘PR24 final determinations Major projects development and delivery’, January, Table 1.

Below, we analyse the full list of 30 major projects by other parameters, such as size of project and project type.

Regarding the size of projects, Figure 3 shows a bimodal distribution by number, with peaks for projects of less than £500m lifecycle TOTEX and projects above £3,000m. The smaller projects are focused on transfer and mixed schemes such as United Utilities’ North West Transfer project (£353m whole-life TOTEX) or the Poole Water Recycling and Transfer project (£306m) being commissioned jointly by Wessex Water and South West Water. The large projects include reservoirs such as the Thames Water South East Strategic Resource Option (£7.5bn) and the Anglian Water Fens (£4.1bn) and Lincolnshire (£4.2bn) reservoirs.

Figure 6 Distribution of projects by expenditure

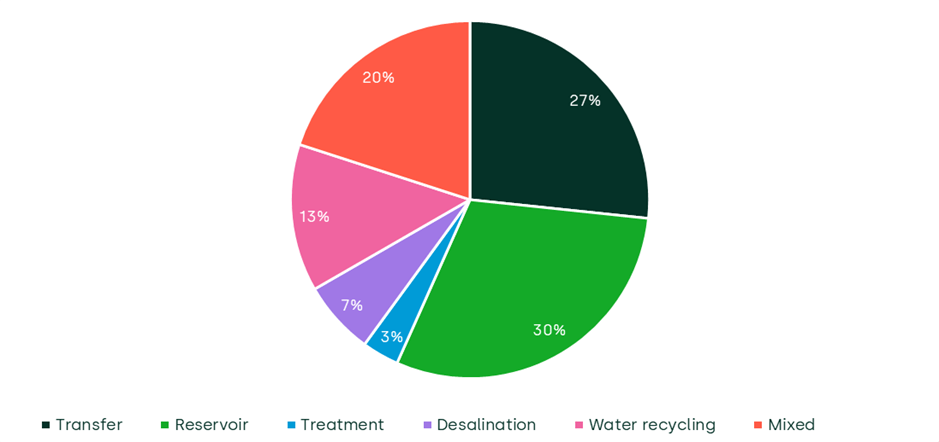

Figure 6 shows distribution of TOTEX by project type and shows that transfer and reservoir schemes dominate, followed by recycling and desalination. However, the first two types differ in terms of expenditure from the latter two, with the former being predominantly CAPEX while the latter two have a much higher proportion of OPEX. This will affect risk exposure, specifically construction risk versus exposure to the risk cost of supplies and maintenance, and possible skill shortages.

Figure 7 Projects by type

Regulatory implications

At first sight, it would appear that investments in DPC will relieve the incumbent water companies of the risk and operation of the new proposed schemes. But this may be optimistic; during commercial negotiations around the agreement with the CAP, the CAP seeks to transfer back much of the risk to the water company.

A further aspect is indirect, arising from the sheer scale of the planned CAP investments and the proposed PR24 major projects. There is the potential for the infrastructure supply chain to be overburdened, with an impact on prices and even reliability, leading to financial penalties under delivery incentives.

Finally, the terms of the CAP contract will affect the risk exposure of the water company and hence the value of the debt and equity holding of its investors. The CAP contract is discussed in more detail below.

CAP contracts

The entire DPC process rests on the content of the CAP contract, and agreement of these contracts is a lengthy and expensive business. To avoid this becoming a deterrent, Ofwat is preparing standard contracts. In its guide, it states:

The Major Projects team is preparing a suite of documents to support Appointees in delivering these schemes, including updated DPC and SIPR guidance, standardised CAP agreements and cost estimation guidance. Additional guidance on compensation events, incentive and penalty mechanisms and bulk supply agreements will follow. It is also expected that RAPID will update their gated guidance throughout the next 12 months.19

Key items in the CAP contract, standard or bespoke, should include the following.

- Treatment of the residual value of the asset at the end of the contract period (the asset is likely to have a life in excess of the contract).

- The use of target costing contracts as opposed to fixed price contracts, to allow for gain and pain sharing between parties and to provide incentives.

- The courses of action in the case of default by either party. If a CAP defaults then the agreement should grant step-in rights to the water company.20 There is also the counterparty risk of the water company going into administration; in that case, the administrator could be expected to preserve the fund flow, to maintain essential services to customers, not least because of possible political intervention if the services are disrupted.

Next steps for investors

The water utility sector offers major opportunities for investors, who may choose to augment their portfolios by either diversifying into this sector or, if already present, diversifying within it. As summarised in Table 1, multiple market engagement processes will be underway in the near future. Due to the differences across projects, investors should consider their strategy towards the pipeline of projects, identifying synergies in the project due diligence process so that cost efficiencies and strategic advantages can be obtained.

Footnotes

1 Ofwat (2025), ‘Building a resilient future: A major projects guide for investors’, May.

2 Based on values submitted by water companies in the long-term delivery strategy sections of the data tables provided alongside their October 2023 business plans.

3 To be precise, £44.5bn in allowed enhancement expenditure before frontier shift efficiency and real price effects. See Ofwat (2025), ‘PR24 final determinations’, January, p. 10.

4 Ofwat (2025), ‘PR24 final determinations Major projects development and delivery’, January, Table 1.

5 Ofwat (2025), ‘Building a resilient future: A major projects guide for investors’, May.

6 However, not all components need be tendered in all cases—for example, the water company may retain responsibility for operation.

7 Water Industry Forum (2021), ‘Making Direct Procurement for Customers a Success’, September, provides a summary of industry views.

8 This includes measures to allow for faster and more flexible delivery, a lower threshold for eligibility, and alignment with national policy statements.

9 Oxera (2015), ‘The Thames Tideway Tunnel: returns underwater?’, Agenda, September.

10 Ofwat (2025), ‘Building a resilient future: A major projects guide for investors’, May.

11 In the current pipeline of projects, SIPR represents 10% of projects by number but 32% by TOTEX.

12 Ofwat (2023), ‘Guidance for Appointees delivering Direct Procurement for Customers projects’, March.

13 Ofwat (2023), ‘Guidance for Appointees delivering DPC project’, March.

14 The scope of the project and its risks are set out in Ofwat (2021), ‘Direct Procurement for Customers – Project Designation Direction issued to United Utilities Water Limited (HARP scheme), December.

15 This is a direction issued by Ofwat that allows the water companies to redirect the customers’ payments due to the CAP.

16 Ofwat (2021), ‘Direct Procurement for Customers (DPC) – Reasons for designating certain components of Anglian Water’s Elsham Transfer and Treatment scheme a DPC Delivered Project’, June.

17 This illustrates the flexibility of DPC and the ability to match ‘horses for courses’ by varying the scope of the CAP agreement.

18 Ofwat (2025), ‘PR24 final determinations Major projects development and delivery’, January.

19 Ofwat (2025), ‘Building a resilient future: A major projects guide for investors’, May, p. 18.

20 For a SIPR, the licence should have conditions on measures of financial sustainability that cannot be breached.

Related

What are the challenges of decarbonising industry in the transition to a green economy?

Earlier this year, the European Commission set out its recommendations for implementing its clean industrial deal—aimed at supporting the EU’s decarbonisation goals while maintaining global competitiveness. Although sectors like electricity generation have seen substantial emissions reductions, many industrial areas still face a steep path ahead. In this episode of Top… Read More

ACM’s draft method decisions for gas and electricity networks

Across Europe, several regulators are consulting on how their frameworks should evolve to respond to the challenges that energy networks face due to climate commitments and the broader macroeconomic environment. The Autoriteit Consument & Markt (the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets, ACM) has now entered this debate with its… Read More