Reflections in the water: insights on Ofwat’s PR24 draft methodology

On 7 July, Ofwat published its draft methodology for its next price review (PR24), setting out in detail how it plans to assess expenditure, financing costs, performance targets and incentives for 2025–30. What are the main components of Ofwat’s proposed methodology, and what might this mean for companies, customers and wider stakeholders?

Key focus

Ofwat’s draft PR24 methodology consultation1 sets out the framework for the next price review in the England and Wales water sector, as well as its expectations of companies regarding their business plans.

The key themes of the consultation include:

- developing a longer-term focus—with adaptive planning of investment given an uncertain future, and focusing on (and incentivising) the outcomes that matter most, now and into the future;

- creating greater environmental and social value—including immediate action on river water quality (storm overflows), moving faster towards net zero, and delivering more catchment- and nature-based solutions;

- a clearer understanding of customer and communities—with collaborative industry research, open meetings on companies’ plans, and a focus on vulnerable customers and affordability;

- driving improvements through efficiency and innovation—with stretching performance standards, strategic development and innovation funding, and rewarding companies that produce the most ambitious business plans.

In many areas, Ofwat has confirmed the intentions set out in its earlier consultation documents. In what follows below, we focus on the areas that are new or substantively changed since Ofwat’s earlier publications.

The main development to be aware of—and one which affects all other aspects of business planning for companies to work backwards from—is the process through which business plans will be assessed.

- Ofwat refers to a two-phased approach to setting the price control (as opposed to a three-phased approach). We understand that this means there will no longer be an Initial Assessment of Plans (IAP). Instead, Ofwat will respond directly to companies’ business plans with a draft determination for all companies (which will include an enactment of business plan incentives), followed by a final determination.

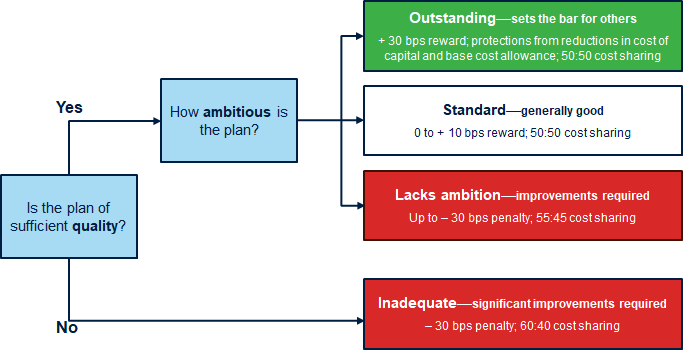

- Ofwat has outlined a new approach to business plan incentives based on four categorisations (outstanding, standard, lacking ambition and inadequate). Companies classified as lacking ambition or inadequate will be subject to upfront penalties of up to 30bps return on regulated equity (RORE) and will also receive asymmetric cost sharing rates. Companies whose business plans are classed as ‘outstanding’ will receive a 30bps RORE reward and will be protected from reductions in allowed returns and base cost allowances following the draft determinations.

Outcomes

Outcomes for customers are discussed in sections 4 and 5 of Ofwat’s draft methodology. Section 4 discusses the high-quality stakeholder research and engagement evidence that will inform companies’ business plans and long-term delivery strategies. Section 5 then outlines Ofwat’s proposals for performance commitments (PCs) and outcome deliver incentives (ODIs).

On the former, there are few surprises. In its May 2021 paper, Ofwat had already proposed to move away from company-specific local customer research and towards a collaborative approach across the sector.2 This followed Ofwat’s concern at PR19 that customers were not always well placed to provide views on technical issues, and that the results from different companies’ research on willingness to pay for improvements in performance in some common areas (e.g. leakage reduction) varied significantly—and for no clear reason.3

Back in October 2021, Ofwat set out a plan to work with CCW and companies to undertake collaborative customer research that, in its view, will generate robust results at company level and allow differences in views between customers of different companies to be clearly understood.4 This would cover common aspects of companies’ business plans—such as common PCs, their associated incentive rates, and affordability and acceptability. In February 2022, Ofwat’s PR24 customer engagement policy also majored on this collaborative approach,5 while other papers have been published since.

So, the Ofwat draft methodology contains no major surprises on the direction of travel. Ofwat states that the common research approach should cover most common performance commitment areas—and that it expects companies to adopt the results of the collaborative research as they build their PR24 business plans. But where does this leave local customer research and engagement? There is a role for this—for example, where there are company-specific outcomes involving investment proposals/schemes, or in the case of bespoke performance commitments and their related ODI rates (see below). However, companies are ‘strongly discouraged’ from undertaking separate research to inform ODI incentive rates for common PCs.

Interestingly, Ofwat is proposing that companies should hold ‘open challenge’ sessions before and after they submit their business plans. Here, customers and other stakeholders would be able to challenge companies on their plans directly in an open forum. Ofwat is working with CCW to develop the details of this proposal. However, a number of companies already hold public sessions with their customers—so it will be interesting to see what emerges.

The approach in Wales will somewhat differ to that set out above, and it will need to take place through the Welsh collaborative approach via the Wales PR24 Forum. The details of how the two approaches will merge are yet to be decided.

The approach that Ofwat intends to take to PCs and ODIs mirrors the above direction of travel for customer research—with more commonality across companies. Since May 2021, Ofwat has published its views on the scope, nature and calibration of PCs and ODIs.6

In its draft methodology, Ofwat wants to focus on key outcomes that are likely to be important in future price reviews, as well as PR24—including the environment, customer service, asset health, and measures to improve outcomes for business customers. The highlights are as follows.

- Bespoke PCs: Ofwat confirms its intention to significantly reduce the scope for companies to propose bespoke PCs, expecting ‘at most two or three’ bespoke PCs per company at PR24.

- Common PCs: Ofwat has clarified its list of proposed common performance commitments for PR24 (21 common PCs for each water and wastewater company in England and Wales, and 11 common PCs for each water-only company). These now include operational greenhouse gas emissions (separately for the water and wastewater services), BR-MeX (business customer and retailer measure of experience), and PCs on bathing and river water quality and on storm overflows. While the PCs are common, performance levels and incentive rates may vary by company.

- Reputational PCs: it would appear that (solely) reputational PCs have been removed from the framework, as Ofwat proposes that all PCs have financial underperformance and outperformance payments. Ofwat notes that an exception would be where outperformance is not possible—such as for statutory compliance PCs, or where a bespoke PC is needed to address poor performance in an area. However, this exception appears to cover the symmetry/asymmetry of the financial incentive as opposed to whether a financial incentive should apply.

- Standard ODI design: Ofwat wants powerful financial incentives, and it also considers that outperformance and underperformance rates should generally be symmetrical. Ofwat will set standard rates by applying a common benefit sharing factor (e.g. 70%) to the estimate of marginal benefits (MB) to a company’s customers of a particular outcome. While these estimates may vary by company, the collaborative customer research discussed above will form the basis for the MB estimates for all common PCs (except biodiversity and operational greenhouse gas emission performance, which will use external valuations).

- Enhanced ODIs: these would apply where a company achieves major performance improvements beyond the best level currently achieved in the industry. These will apply to all companies for a selection of the common PCs. In contrast to most other ODIs, these will have an outperformance element only, reflecting the sector-wide benefits from very high performance in setting PCs at future price reviews. Enhanced rates would be set at twice the size of standard rates.

- Risk exposure: Ofwat expects revenues at risk from ODIs to be between ±1 to ±3% return on regulatory equity (RoRE) each year (excluding the experience measures C-MeX, D-MeX and BR-MeX). It intends to manage overall ODI risk primarily through an ‘aggregate sharing mechanism’, which will share net ODI payments between customers and companies once they reach certain thresholds each year.

Interestingly, in addition to the incentives provided by ODIs, Ofwat wants to introduce additional incentives such that customers are protected against under- or non-delivery of material funded enhancements. Where the investment is material but the outcome cannot be directly linked to a PC, Ofwat intends to set a Price Control Deliverable (PCD). This borrows language from the Ofgem approach to specific material enhancements. PCDs allow enhancement funding to be returned to customers in the event of under- or non-delivery of outputs or outcomes associated with enhancement expenditure.

Cost assessment

As it did in PR19, Ofwat is calling for a ‘step change’ in efficiency improvements, citing a purported drop in annual efficiency improvements since 2011. Generally, there is relatively little within the cost assessment and expenditure allowances section of the methodology that diverges from Ofwat’s previous statements, which may partly be due to the fact that the CMA upheld much of Ofwat’s approach at PR19. Some of the changes, or elaborations on previous plans, are discussed below.

- Accounting for future changes in required spending: base cost modelling is most appropriate when applied to costs that are relatively stable over time. Some of Ofwat’s proposals could help to capture any requirement for a step change in spend:

- building on approaches at PR19, Ofwat will also use forecasts for sewage treatment complexity (e.g. UV treatment and phosphorus removal) going forward;

- similar to Ofgem’s approach, Ofwat is also considering the use of business plan data on base costs to help reflect companies’ views on future cost pressures, though Ofwat notes this would have to be used with caution;

- chiming with an overall focus on long-term planning, Ofwat will seek to improve knowledge of asset health while also asserting that the current regulatory regime has not biased companies towards a short-term focus (see below).7

- Increased use of external benchmarks from other sectors: this will expand on previous use of external benchmarks when setting allowed costs of customer service and bad debt.8

- Performance commitments: Ofwat proposes a number of changes to performance commitments to make them better at providing cross-company comparisons, take account of complex trends, and reflect delayed or cancelled enhancements.

- Performance commitments should be common unless proven otherwise: these proposals could be more challenging for companies, and there has been discussion as to whether performance commitments need to be normalised for comparability across companies. Ofwat has argued, however, that given that differences in external factors between companies are accounted for in its modelling of base costs, common performance commitments can be applied, rather than adjusting for exogenous factors, to avoid ‘double counting’. This is unless the exogenous drivers of the PCs are not included in the base cost models. Additionally, two PCLs that will be mandatorily common across companies are the compliance risk index (CRI) and discharge compliance.9

- Performance commitment forecasts will not necessarily be linearly extrapolated: Ofwat had argued that the 2023/24 baseline would be linearly extrapolated, which could be quite challenging for some companies. However, given that there could be diminishing returns to further service improvements and following the successful appeal to the CMA in 2019, Ofwat proposes that performance levels will now be extrapolated from historical trends on a linear, diminishing or alternative relationship trend where appropriate.

- Enhancement expenditure: Ofwat has signalled it is aiming to undertake more modelling in this area, extending the use of econometric modelling for unit costs, while continuing to use benchmarks where appropriate.10

- Enhancement projects: companies should undertake enhancement projects that specifically contribute to net zero, and they should make use of nature-based solutions where possible.

- Funding uncertainty for nature-based solutions: additionally, in order to mitigate the purported previous funding uncertainty for nature-based solutions, as well as the bias that this has created against using these measures, Ofwat has proposed two possible solutions:

- capitalisation of the net present value of the whole-life operating expenditure of nature-based solutions, with this value being added to the companies’ Regulatory Capital Value—this option has been proposed, but it will only be implemented if deemed feasible;

- setting a 10-year operating expenditure allowance, to be recovered over two price control periods, related to nature-based solutions that are based on on-going operating expenditure.

Risk and return

While keeping the methodologies on financial parameters broadly consistent with PR19, Ofwat is considering a few changes that respond to the outcome of the CMA PR19 appeals and the market environment.

In terms of RCV indexation, Ofwat has confirmed its intention to switch from using a combination of RPI and CPIH indices to full CPIH indexation. This approach is aligned with Ofgem’s RIIO-2 price controls for energy networks.

Cost of equity

We outline Ofwat’s approach to each Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) parameter below. For the cost of equity as a whole, Ofwat maintains its position that market-to-asset ratio (MAR) analyses play an important role as cross-checks for the CAPM-based cost of equity estimate.

Risk-free rate

Similar to PR19, Ofwat proposes to use inflation-linked gilts to proxy the risk-free rate and considers long-term SONIA swap rates and nominal gilt yields as potentially useful cross-checks.

Given that inflation-linked gilts are linked to RPI, the yields need to be converted into CPIH-real terms. This conversion has become less certain because of the intention of the UKSA to align the definition of RPI inflation with CPI inflation after 2030. Ofwat’s current preferred approach is to set a lower than the long-term RPI–CPIH wedge. In particular, it intends to rely on OBR’s RPI and CPI forecasts until 2030, after which RPI is expected to be fully aligned with OBR’s long-term CPI forecast (i.e. an RPI-CPIH wedge of zero).11

Ofwat does not intend to adjust for a convenience yield—it previously pointed out that although the CMA has accepted the concept of the convenience yield at the PR19 appeals, the CMA did not consider Ofgem’s approach of relying on index-linked gilts to be wrong at the RIIO-GD2/T2 appeals.

Ofwat has previously considered risk-free rate indexation and decided against it.

Total market return

For PR24, Ofwat proposes to retain a fixed total market return (TMR) approach by deriving a range for the TMR using ex post and ex ante historical approaches (i.e. not using forward-looking approaches as primary evidence) and inferring equity risk premium (ERP) from TMR and RFR.

Beta

As in PR19, Ofwat plans to place most weight on the betas of Severn Trent and United Utilities, i.e. well-established ‘pure-play’ water companies.12 To ensure that unusual events such as COVID-19 are accounted for appropriately, Ofwat intends to consider 2-year, 5-year and 10-year estimation periods.

For PR19, Ofwat and the CMA de-levered raw equity betas, using the actual gearing of comparators, and re-levered using a notional gearing assumption. For PR24, Ofwat proposes to adopt a ‘more consistent CAPM-WACC’ approach under which debt beta would be set at the level to make the CAPM-WACC calculation (using the expected cost of new debt) insensitive to gearing. Illustrated with the PR19 numbers, this approach would lead to a 4bps lower allowed return on capital.

Cost of debt

Ofwat intends to retain the general PR19 methodology for the allowed return on debt for PR24 by setting separate allowances for the cost of embedded and cost of new debt.

- Cost of embedded debt. The derivation of the cost of embedded debt allowance has provisionally changed compared to PR19, with most weight now placed on the balance sheet approach (i.e. the average actual cost of debt of the companies in the industry) and the benchmark index approach used as a cross-check. In PR19, it was the other way around. For the benchmark index cross-check, Ofwat does not propose a defined length of the trailing average, but it states that assuming 20-year tenor issuances, which is linked to the choice of the trailing average, potentially overstates the actual cost of borrowing.

- Cost of new debt. Ofwat proposes to continue indexing the allowance to the average of the A and BBB iBoxx GBP non-financials 10+ indices, as at PR19. To address any potential outperformance relative to the benchmark index, Ofwat favours an ex post adjustment estimated as the actual average spread-to-benchmark for 2025–29. This is a change from PR19, when the adjustment was set ex ante.

An allowance for issuance and liquidity costs is expected to be set at the PR19 level of 10bps. Ofwat does not specify how it proposes to deflate the nominal estimate of the cost of debt allowance.

Small companies will be able to apply for a company-specific adjustment without satisfying a customer benefit test, which was required in PR19.

Notional gearing

Without specifying a proposed level of the notional gearing explicitly, Ofwat mentions the benefits of adopting a lower notional gearing level at PR24 compared to PR19, when it was set at 60%, and states that a change to 55% is not unprecedented. Ofwat highlights that this decision is independent of financeability and serves as a signal to companies to ensure that they have a sufficient equity buffer to cope with the increasing uncertainty.

Financeability

As in PR19, Ofwat suggests that companies target credit ratios of at least BBB+/Baa1. However, it does not consider that each financial ratio needs to fall within the guidance range for BBB+/Baa1—other factors can counterbalance the impact of a single weak metric.

Financial Resilience

In PR19, Ofwat used a Gearing Outperformance Sharing Mechanism (GOSM) to disincentivise companies from adopting highly geared capital structures—given concerns it had regarding financial resilience. The mechanism was struck out by the CMA for the appellant companies.

Ofwat intends to publish a separate consultation paper outlining options to strengthen the customer protections in relation to companies’ financial structures. Currently, it suggests that regulatory ring fencing, as well as monitoring and reporting measures that are proposed to be strengthened, remove the need for a specific incentive mechanism in PR24. However, it does not rule out the possibility of applying an incentive-based mechanism.

In its previously published discussion papers, Ofwat also consulted on changing a dividend lock-up threshold from a BBB- negative outlook to a higher one (e.g. BBB with negative outlook)—it does not provide an update on this proposal.

Finally, Ofwat encourages companies to put forward voluntary outperformance sharing commitments.

Long-term delivery strategies

As mentioned elsewhere in this article, Ofwat has taken steps to promote a longer-term approach in PR24. The draft methodology confirms Ofwat’s position that companies should develop their 2025–30 business plans in the context of 25-year delivery strategies, and that they should make use of adaptive planning. To support this aim, it states the following.

- It may allow (operating) expenditure for nature-based solutions to be added to the RCV to provide long-term certainty around cost recovery (as discussed above).

- It outlines a menu of (limited) options for how it could accommodate any changes in expenditure required to secure asset health, alongside a recommitment to explore and test wider measures associated with the health and performance of water and wastewater assets.

- It reaffirms that it is the responsibility of companies to ensure that they commit sufficient expenditure to asset health—noting that it does not place requirements on how companies spend their allowance—and notes that companies have an obligation to meet their statutory obligations and submit business plans commensurate with them.

- Were the historical and/or forecast data submitted by the industry as a whole to increase to reflect greater capital maintenance requirements, Ofwat’s methodology leaves the door open to allowing more expenditure, although its higher-powered business plan incentives (see below) may discourage companies from committing more than the minimum spend necessary for AMP8.

- If companies feel more should be spent on asset maintenance, there is also scope to apply for a cost adjustment claim—albeit with a high evidential bar and a bias towards current levels of spend.

- Ofwat has committed to providing greater clarity on the treatment of multi-period investments (which are not suitable for DPC or SIPR). These will be assessed as part of the AMP’s business plan, with the proportion of scheduled investment during that period and the next treated separately. This means that companies will be required to request a new expenditure allowance during PR29, but they will not be able to request additional cost allowances for any portion of the project that is scheduled within the 2025– 30 period.

- While Ofwat is not minded to define PR29 incentive rates during this price review, it states that it is ‘open to proposals to provide greater clarity over our intended approach in PR29 where it can be demonstrated that this would clearly be in the interests of customers’.13

Scope of controls and markets

Ofwat has also provided greater detail on the scope of price controls and its approach to promoting effective markets. These proposals include:

- as at PR19, applying a total revenue control for water resources, network plus water, and network plus wastewater, as well as an average revenue control approach for residential retail;

- moving from a total revenue control approach to an average revenue control approach in bioresources, in line with its December 2021 consultation;14

- retaining the water trading incentive in its current form to 2029 and committing to a revised incentive being in place for PR29;

- removing site-specific developer services from the network price controls where there is evidence of strong competition;

- confirmation that Ofwat will not take forward work on developing water resource bilateral markets.

Relatedly, Ofwat has signalled its plans for greater use of its competitive delivery model (direct procurement for customers, DPC) for large projects. Companies will now be expected to pursue DPC as the default option for schemes with whole life TOTEX in excess of £200m per annum.

This represents a higher threshold than at PR19 (£200m instead of £100m whole life TOTEX) but also a change in expectation; previously, companies were allowed to propose DPC, whereas now they will be expected to include them as a default option, and they will be penalised if they do not consider eligible schemes. This fits with a broader government policy to promote competitive delivery of infrastructure assets, as set out in BEIS’s January 2022 ‘Economic Regulation Policy’ report.15

Business plan incentives

There are also developments in the way that Ofwat intends to provide companies with incentives to submit high-quality and ambitious business plans—through a combination of reputational, financial and procedural incentives.

A key change at PR24 concerns the staging of the assessment process. At PR19, following the submission of company business plans, Ofwat undertook an initial assessment of plans (IAP). Companies that performed best at this stage were subsequently ‘fast-tracked’ and received an early draft determination. The remaining (‘slow-track’) companies needed to revisit their plans, resubmit them, and subsequently receive their late draft determinations. final determinations for all companies then followed.

However, in its May 2021 initial views paper, Ofwat stated that at PR19, while companies said they valued the feedback received at the IAP stage, there was limited movement in key aspects of companies’ plans—suggesting the additional step may have been of limited value. While various options were discussed in that paper for PR24, the decision in the July 2022 consultation appears to be to scrap the IAP stage.

Instead, Ofwat will undertake a business plan assessment at PR24 that will, for each company, influence the draft determination that it receives at the same time (including the business plan incentives that are applied). In effect, this means that water companies will need to ensure that their PR24 business plans are robust to scrutiny in the first instance—there may be limited scope for a second chance. Interestingly, in its May 2021 paper, Ofwat indicated that merging the initial assessment of plans and draft determination stage together would mean that companies would not be required to resubmit their plans (rather, they would only need to respond to Ofwat on the draft determinations).16 In contrast, in its July 2022 draft methodology, Ofwat states that companies should make their ‘first submission their best possible submission’ and that ‘companies that fail our quality assessment will have to make significant changes to their plans’ (emphasis added).17

This indicates that some form of resubmission is possible—however, no detail is provided around this process, and it is unclear that resubmission would in any case result in a change in a company’s categorisation and the business plan incentives applied: Ofwat notes that it may, exceptionally, move a company out of the lowest categories, but that it would ensure that such companies were worse off than those who provided their best plan at the first opportunity.18

The revised approach also cuts the determination stage from three phases to two—thus eliminating the concepts of ‘fast-’ and ‘slow-tracking’ (a change that mirrors the approach followed by Ofgem in RIIO-2—where fast-tracking was also ended). However, Ofwat still wants to provide rewards to those companies that submit high-quality and ambitious business plans at PR24. As shown in Figure 1, companies then classed as ‘outstanding’ will benefit financially from a +30bp uplift on regulated equity.

Figure 1 PR24 business plan incentive rewards and penalties

From a procedural perspective, companies classed as ‘outstanding’ will also be protected from any downward movements (stemming from Ofwat decisions) on base costs or cost of capital between the draft and final determinations. Ofwat acknowledges that this protection was missing at PR19 (relative to the prior price review, PR14). Given the company feedback received, Ofwat introduced the modification.19

Interestingly, as evident from the bottom two categories in Figure 1, companies that submit plans that lack ambition or are of low quality will receive financial penalties (of up to -30 bps)—and they also will be able to retain a lower share of cost outperformance once prices are set. This is of particular interest given that at PR19 all but three companies fell into the bottom two categories that applied at the time (‘slow track’ or ‘significant scrutiny’).

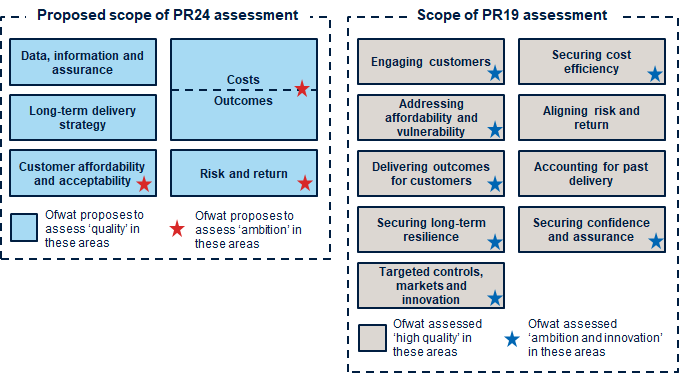

As shown in Figure 2, Ofwat will assess various areas in PR24 to arrive at its assessment (with a condensing of categories relative to PR19). While accounting for past delivery is no longer an explicit area for assessment, elsewhere in the consultation Ofwat states that it expects companies and their boards to carefully consider how their performance during 2020–25 should inform their proposals for 2025–30 and beyond (including in relation to setting performance expectations and funding service enhancements).20

Figure 2 Proposed scope of PR24 BPI assessment compared to PR19

Clearly, the above process is intended to encourage companies to work backwards from the incentives available—and to create high-quality business plans in the first instance. To benefit from the ‘outstanding’ classification, a company will need to follow the methodology to the letter. The issue in practice will be whether the available incentives are enough, and if so, whether to obtain them companies think that their business plans would be deliverable.

Notably, while three companies achieved ‘fast track’ status at PR19, Ofwat did not place any companies in the best category: ‘exceptional’. According to Ofwat, the bar for this category was set very high, and while some companies met the standard in some areas, no company demonstrated enough ambition and innovation across its plan as a whole.21 So the question, then, is: will we see any business plans classed as ‘outstanding’ at PR24?

1 Ofwat (2022), ‘Creating tomorrow, together: consulting on our methodology for PR24’, July.

2 Ofwat (2021), ‘PR24 and beyond: Creating tomorrow, together’, May.

3 For a discussion, see: Oxera (2021), ‘Ofwat and future price reviews: a stake in the ground’, Agenda, 25 June.

4 Ofwat (2021), ‘PR24 and beyond position paper: Collaborative customer research for PR24’, October.

5 Ofwat (2022), ‘PR24 and beyond: Customer engagement policy – a position paper, February.

6 Source: Ofwat (2021), ‘PR24 and beyond: Performance commitments for future price reviews’, November; Ofwat (2022), ‘PR24 and beyond: a discussion paper on outcome delivery incentives’, February.

7 Ofwat (2022), ‘PR 24 Draft Methodology’, 7 July, p. 70.

8 Ofwat (2022), ‘PR 24 Draft Methodology’, 7 July, p. 70.

9 Ofwat (2022), ‘PR 24 Draft Methodology’, 7 July, pp. 73–74.

10 Ofwat (2022), ‘PR 24 Draft Methodology’, 7 July, p. 33.

11 CPI is used as a proxy for CPIH.

12 Ofwat notes that Pennon has been a ‘pure-play’ water company since June 2020; however, difficulties remain in accounting for cash holdings from the disposal of its waste management subsidiary. Ofwat will consider whether to use data from Pennon ahead of finalising its methodology.

13 Ofwat (2022), ‘Creating tomorrow, together: consulting on our methodology for PR24. Appendix 12: Business plan incentives’, July, p. 64.

14 Ofwat (2021), ‘Our proposed approach to funding bioresources activities at PR24’, 9 December, accessed 12 July 2021.

15 Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (2022), ‘Economic Regulation Policy’, January.

16 See the discussion of Option 1 in Ofwat (2021), ‘PR24 and beyond: Creating tomorrow, together’, May, p. 45. Ofwat appears to have adopted some form of Option 1 in its July 2022 consultation.

17 Ofwat (2022), ‘Creating tomorrow, together: consulting on our methodology for PR24’, July, Section 11.3, p. 136; Section 10.10.3, p. 132.

18 Ibid. Section 11.3, p. 136.

19 Ofwat (2022), ‘Creating tomorrow, together: consulting on our methodology for PR24. Appendix 12: Business plan incentives’, July, pp 9–10.

20 Ofwat (2022), ‘Creating tomorrow, together: consulting on our methodology for PR24’, July, Section 10.10.3, p. 126.

21 Ofwat (2019), ‘PR19 final determinations: Policy summary’, December, p. 22.

Contact

Leon Fields

Senior ConsultantContributors

Related

Related

The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say? (Part 2 of 2)

On Thursday 23 October in Brussels, Oxera hosted a roundtable discussion entitled ‘The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say?’. In the second of a two-part series, we share insights from this productive debate. The discussion took place in the context of an… Read More

The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say? (Part 1 of 2)

On Thursday 23 October in Brussels, Oxera hosted a roundtable discussion entitled ‘The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say?’. In the first of a two-part series, we share insights from this productive debate. The discussion took place in the context of an… Read More