Zombie firms: how can new assessment tools effectively direct credit supply?

While the post-pandemic economic recovery continues, governments and credit institutions will need to decide where to direct their financial support, selecting companies with a strong potential for growth rather than those that are destined to decline. This is not a straightforward task, since post-COVID-19 events are influencing the business models of entire industries and affecting companies’ short-term economic performance. As Oxera Associate Fabio Menghini explains, the effectiveness of traditional credit risk assessment tools may need to be re-evaluated.

Now that the ‘first aid’ phase is almost complete, governments and banks will need to sustain economic recovery with more focused actions, turning their attention to strengthening economic growth and securing healthier financial margins and sustainability milestones. However, the economic slowdown associated with the COVID-19 pandemic could make reaching these goals more challenging. Slow growth and low interest rates, as well as the large subsidies provided during 2020, may have influenced companies’ balance sheets, making businesses’ economic fundamentals less recognisable.

Market distortions could therefore arise if companies that are worth sustaining are not identified, or—worse—if economically inefficient operators are allowed to continue. There could be a failure to focus on those areas where incentives and financing should be directed to support the economic recovery.

To solve this problem, the traditional tools employed to assess credit risk and a company’s ability to generate a profit should be supported by new evaluation approaches based on early recognition of current and future trends.

Zombie firms

In this context, the notion of ‘zombie firms’ has recently gained prominence, to identify firms with earnings that are insufficient to service their debt. A recent study by Oxera consultants looked at this phenomenon in a number of European countries.1 The authors’ aim was to identify companies that were ‘zombies’ before the pandemic and that are likely to remain so in the coming years.

The study also aimed to identify companies that could become zombies as a result of the economic impact of the pandemic, and found that approximately 15% of European non-financial companies could be defined as zombies. These are companies that are technically bankrupt but somehow manage to survive. Many consider that this is due to banks’ credit strategies.

The Economist comments that ‘after years of loose monetary policies, banks tend to keep sick companies alive by allowing them to repay old debts with new loans’, where once they would have required companies to go bankrupt in order to recover at least part of their loans.2

Indeed, banks with low profitability, due to equally low interest rates, are more likely to support zombie companies. This seems to be a widespread phenomenon among European and international institutions.3

The survival of this type of company is problematic. In fact, it leads to a sub-optimal allocation of resources that could otherwise be directed towards healthy businesses, which are able to grow, make investments, and increase employment.

In addition, since zombie firms lack the resources to invest and also have lower margins than competitors, they are able to have negative impacts on their industries. Players in those industries will suffer from the presence of the zombie firms: since prices are kept lower than usual, the labour market becomes blocked and new innovative entrants are discouraged.4

Possible effects of measures to support businesses

If low interest rates are one of the chief causes of the survival of zombie firms, it is not surprising that there has been widespread alarm regarding a possible ‘zombification’ of the whole economy as a result of business support measures in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

A large proportion of bank loans now benefit from government guarantees, while moratoria lengthen the time it takes to repay borrowed capital, which could conceal irreversible crisis situations. Accordingly, there are growing concerns that overburdening the corporate sector with debt in response to the crisis could create a new wave of zombie companies, with negative consequences for recovery plans.

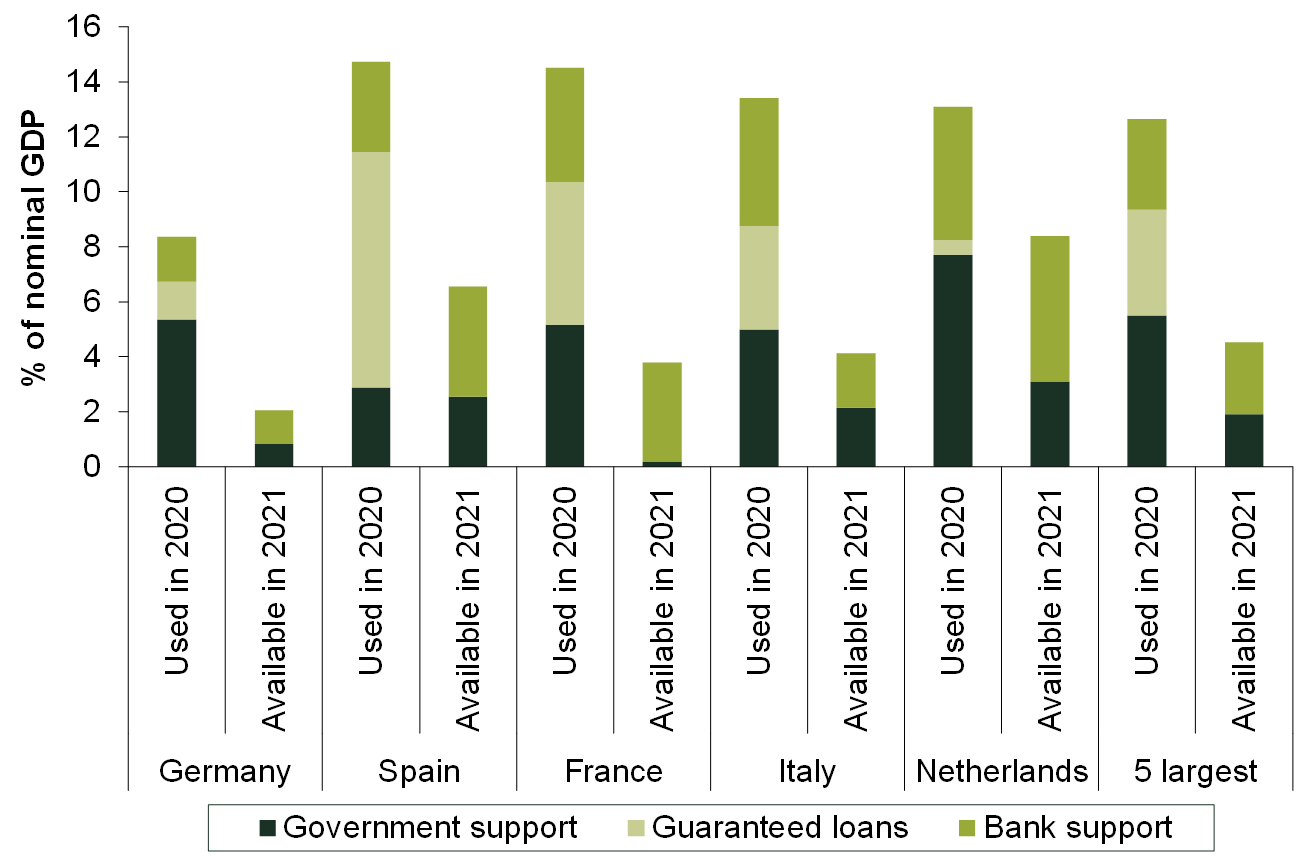

By way of example, the following table from the study of non-performing loans summarises the interventions planned in the richest eurozone countries.5

Figure 1 Government and bank support to the non-financial private sector in the five largest eurozone economies

The European Central Bank recommends that banks carefully assess the level of risk, and implement risk assessment and early warning systems.6 The matter of risk assessment deserves attention, especially in the context of Mediterranean countries. Here there are large numbers of small enterprises, which are usually associated with a lower level of profitability7 (and therefore a reduced ability to repay debt) and a greater difficulty in accessing financial resources outside the banking sector in terms of listing companies or opening them to private equity investments. Notably, a 2017 study from the OECD8 has presented worrying estimates of the potential number of zombie companies in Greece, Spain and Italy.9

Correct assessments are essential for effective credit allocation

Having said that, there is no single point of view on the prevalence and impact of zombie companies. For instance, according to a study published by the Bank of Italy,10 the inferred number of zombie companies varies depending on which balance sheet indicators are used in the assessment. The same study suggests that the negative impact of zombie companies on their respective sectors is more limited than is argued elsewhere. Moreover, an observation of the same companies over time reveals that around one-third of them cease to be zombies within three years.

The authors of the Italian study therefore highlight the risk of overestimating the scale and severity of the zombie firm phenomenon. This could lead to unjustified closures, which in turn would lead to unemployment and disuse of production factors, thus contributing to a fall in demand. These difficulties could be particularly severe for countries (such as those in Southern Europe) that were already in recession before the pandemic struck.

In summary, it appears to be more difficult to distinguish companies with marginal performance from those that are following different (or new) growth trajectories. For instance, there could be healthy companies that are suffering only a temporary liquidity crisis due to a lack of components, or others that are reorganising their production process and even entering new markets to leverage opportunities generated by the post-COVID-19 situation. All of these actions require strong financial investments but do not necessarily signal intrinsic financial weakness.

This is undoubtedly a major challenge for banks: they will have to first be able to avoid an increase in non-performing loans (NPLs), and then support those companies that are experiencing a temporary crisis and yet have the potential to deliver future value. Otherwise, we would be cutting the legs from the recovery rather than supporting it.11

An ‘unconventional’ crisis

In my view, there is a risk of not being able to identify real zombie firms, and—which is worse—penalising potentially high-growth companies.12 On the one hand, regulators are paying a great deal of attention and their focus is naturally on safeguarding banks’ balance sheets. On the other hand, the tools for identifying zombie and (more importantly) non-zombie companies that are experiencing an economic downturn are still limited.

The challenge here is particularly acute, since the economic crisis brought about by COVID-19 has very different features from those of the past. It is not, for example, a crisis of overproduction caused by a fall in demand. On the contrary, it has been artificially created by blocking supply, primarily for health protection purposes. The classical interpretation patterns are of little help here.

In addition, the signs of recovery that we are witnessing highlight the need to be prepared for a volatile economy and unexpected or abnormal movements. This requires an unusual effort to prevent and mitigate risks and to identify exactly where and how changes will occur. On this basis, additional tools for a selective, effective and completely different credit management will have to be developed.

A few examples may shed some light on what this means, particularly regarding the variables that need to be considered in order to identify ‘zombification’.

The past is not always a good adviser

Predictive models, which are often recommended by supervisory authorities, may lead to incorrect evaluations of the economic health of a given company. These models, in fact, are based mostly on the past behaviour of companies that have already failed: if a given company’s performance matches the pre-crisis performance of such failed firms, this may mean that the company is destined to default too.

But if the context is new and unusual as in the current case, relying on past data and time series could lead to misleading conclusions. The pandemic shock often affected companies that were operating in vital industries. What led to the failure of a company in the pre-COVID-19 period is not necessarily a good indicator of the level of risk in the current phase. Similarly, companies’ classification as zombies in past crises will not necessarily mean that they are zombies today.13

The limits of sectoral analyses

Recovery has not affected all sectors in the same way, as was to be expected: industries with more prolonged closures have suffered more than others. However, stopping the analysis at sector level would be misleading. Again, it should be borne in mind that the post-COVID-19 economy will look different, and what that will look like is gradually being defined.

In the restaurant industry—one of the sectors most affected by the pandemic—some operators have seen their turnover growing thanks to the introduction of innovative solutions, from home deliveries14 to the development of models based on ‘dark’ or ‘cloud kitchens’.15

Online sales of clothing products have increased by almost 11% in one year.16 At the same time, research carried out in the USA has shown that 50% of American families have reduced their spending on clothing and have lost their brand loyalty in favour of cheaper or more easily available products. Operators in the same sector have therefore recorded very different economic performances.

Although the car industry was one of the hardest hit by the COVID-19 crisis, there was strong growth in second-hand car sales,17 driven by the search for a method of transport that guaranteed social distancing, low interest rates, and the prudent behaviour of households in using their savings amid conditions of uncertainty. Lastly, while the large supermarket chains experienced vertical falls in turnover, local shops saw their turnover appreciably increasing.18

It is therefore dangerous to associate a company with the performance of its sector; what determines its performance seems rather to be its business model and its ability to adapt quickly to changing external conditions.

Health crisis and innovation

Many companies reacted to the lockdown and the pandemic by bringing their best skills to bear in solving the major initial health challenges, such as the lack of ventilators, masks and sanitising materials.

For some, this was a temporary phenomenon, while in other cases these initiatives generated new business units. The profit and loss account of these experiences is, of course, negative in the short term, but they are synonymous with entrepreneurship and resilience. A traditional reading of these companies does not capture these values.19

Supply chain and production networks

Thousands of companies produce intermediate components and, due to the nature of their products, supply many sectors. These have suffered supply and production disruptions to varying degrees. They are now at different stages of recovery, depending on the markets that they serve, and also on their ability to extend beyond their traditional boundaries—that is, to leave their original supply chains and find new outlets for their products.

Many of these companies may experience negative economic performance, as they face initial costs due to entering neighbouring markets. But these costs should generally be considered as limited in time and, in any case, will be linked to the success of the company’s market diversification strategy.

Unexpected shocks

Since last autumn, there has been an increase in the price of raw materials and resources—steel,20 copper, aluminium, and, more recently, energy—and a reduction in the availability of supplies, due to a slowdown in production in the first phase and expectations of strong growth in demand in the next. Companies are finding that they are paying much higher prices, and that contracts are often already closed, such that these increases cannot be passed on to the final customer. This situation was largely unforeseen and is having significant consequences for many firms, especially those for which the raw material component of the final value is particularly high. The global supply chains have acted asymmetrically in this case, rapidly reducing production capacity during the most acute phase of the crisis, without being able to rebuild it just as quickly when the economic cycle starts up again.

Knowing how to predict and interpret these phenomena, their impact on companies’ balance sheets and their duration is very important. Some of these shocks may have limited duration and be less severe in the longer term.

Geographical variation

It is now clear that economic recovery trends show significant differences by geographical region. The pace of recovery by region could temporarily affect export companies, as well as their suppliers, depending on their destination markets. Here, again, the impacts on the companies’ profits and losses may be important but should, by their nature, be temporary.

Adopting new visions and tools

On the eve of the launch of new and important economic measures to support businesses, it will therefore be appropriate to take note of the differences with the past and the large number of variables to be considered when planning the required interventions.

This will be particularly important for individual governments that are moving from indiscriminate forms of support to selective interventions, as well as for credit institutions. They will require granular analytical approaches to detect the origins of negative performance by companies and classify them according to unconventional parameters. It will be necessary to forecast trends and measure their duration, to anticipate impacts, and to distinguish companies that are in structural crisis from those that are undergoing a transition to the new normal, or that have simply suffered from a prolonged period of closure. This is not an easy task, but it is crucial if economic recovery is to be achieved while mitigating the risk of a growth in the stock of NPLs.

Fabio Menghini

Fabio has more than 20 years of experience in the financial and payments industry working with leading domestic players and multinational incumbents.

He is Adjunct Professor of Industrial Strategy and Corporate Finance at Università Politecnica delle Marche (UNIVPM) in Ancona, Italy. He has authored several publications concerning the digital and industrial economy.

1 Haynes, J., Hope, P. and Talbot, H. (2021), ‘Non-performing Loans-new risks and policies?’, Study Requested by the ECON committee, European Parliament, Economic Governance Support Unit (EGOV) Directorate-General for Internal Policies, PE 651.388, March.

2 The Economist (2020), ‘Why Covid-19 will make killing zombie firms off harder’, 26 September.

3 Laeven, L., Schepens, G. and Schnabel, I. (2020), ‘Zombification In Europe In Times Of Pandemic’, VOX EU CEPR, 11 October.

4 Banerjee, R. and Hoffman, B. (2018), ‘The Rise Of Zombie Firms: Causes And Consequences’, BIS Quarterly Review, September, pp. 67–78.

5 Haynes, J., Hope, P. and Talbot, H. (2021), ‘Non-performing Loans-new risks and policies?’, Study Requested by the ECON committee, European Parliament, Economic Governance Support Unit (EGOV) Directorate-General for Internal Policies, PE 651.388, March, p. 40.

6 European Central Bank (2020), ‘Are the pandemic relief measures creating zombie firms?’, Banking Supervision, 14 December.

7 Hall, M. and Weiss, L. (1967), ‘Firm Size and Profitability’, Review of Economics and Statistics, 49:3, pp. 319–31. See also Doğan, M. (2013), ‘Does Firm Size Affect The Firm Profitability? Evidence from Turkey’, Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 4:4, pp. 53–9.

8 McGowan, M.A., Andrews, D. and Millot, V. (2017), ‘Insolvency Regimes, Zombie Firms And Capital Reallocation’, OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1399, 28 June.

9 See Haynes, J., Hope, P. and Talbot, H. (2021), ‘Non-performing Loans-new risks and policies?’, Study Requested by the ECON committee, European Parliament, Economic Governance Support Unit (EGOV) Directorate-General for Internal Policies, PE 651.388, March, p. 37 for an estimate of the number of companies that would have suffered severe liquidity problems in the first phase of the pandemic in the absence of government support interventions.

10 Rodano, G. and Sette, E. (2019), ‘Zombie Firms In Italy: A Critical Assessment’, Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers), No. 483, Banca D’Italia, January.

11 See also Haynes, J., Hope, P. and Talbot, H. (2021), ‘Non-performing Loans-new risks and policies?’, Study Requested by the ECON committee, European Parliament, Economic Governance Support Unit (EGOV) Directorate-General for Internal Policies, PE 651.388, March, p. 8: ‘The key challenge for policymakers is to ensure that the financial system is well placed to support those firms whose continuation value is larger than their liquidation value. These are the (non-zombie) firms with viable business plans, which may need some liquidity support to help them through the crisis’.

12 This seems to be confirmed by the evidence emerging from the results of the recent Euro Area Bank Lending Survey: ‘Banks reported a stronger net tightening of credit standards for loans to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (25%) than for loans to large enterprises (16%), as well as a stronger tightening for long-term loans (26% vs. 19% for short-term loans). In the first quarter of 2021, banks expect a continued net tightening of credit standards on loans to firms (20%)’.

13 See, for instance, Laeven, L., Schepens, G. and Schnabel, I. (2020), ‘Zombification In Europe In Times Of Pandemic’, VOX EU CEPR, 11 October.

14 See Hospitality & Catering News (2020), ‘UK restaurant takeaway sector 2020 growing faster than any other’, 15 February.

15 Peterson, R. (2021), ‘Top 3 Takeaways from FSTEC 2021: The Cloud, Integrated POS, Ghost Kitchens’, Oracle Food and Beverage Blog, 6 October.

16 Based on March 2021 figures—see Hillier, L. (2021), ‘Stats roundup: the impact of Covid-19 on ecommerce’, Econsultancy, 20 September.

17 Ludwig, S. (2020), ‘20 Small Businesses Thriving During Coronavirus’, CO—, US Chamber of Commerce, 24 March.

18 Ibid.

19 See Bergami, M., Corsino, M., Daood, A. and Giuri, P. (2021), ‘Being resilient for society: evidence from companies that leveraged their resources and capabilities to fight the COVID-19 crisis’, R&D Management, RADMA and John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

20 See Myllyvirta, L. (2021), ‘Analysis: China’s carbon emissions grow at fastest rate for more than a decade’, CarbonBrief, 20 April; and Bellomo, S. (2021), ‘Meno acciaio dalla Cina (ora che forse ci servirebbe)’, Il Sole 24 Ore, 24 July.

Download

Related

Ofgem’s RIIO-3 Sector Specific Methodology Decision

On 18 July 2024, Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Decision (SSMD) for the forthcoming RIIO-3 price control period for electricity transmission (ET), gas transmission (GT) and gas distribution (GD) networks.1 This follows Ofgem’s consultation on the matter in December 2023.2 RIIO-3 will last for… Read More

The future funding of the England & Wales water sector: Ofwat’s draft determinations

On Thursday 11 July, Ofwat (the England and Wales water regulator) published its much anticipated Draft Determinations (DDs). As part of the PR24 price review, this sets out its provisional assessment of allowed revenues and performance targets for AMP8 (2025–30)—and will be of great interest to water companies, investors,… Read More