Water non-household retail markets: water choice to make

The Water Act 2014 provides the legislative framework for non-household water retail competition to be introduced in England in April 2017. While water companies have been focusing on compliance with the new arrangements, they will soon be faced with a series of important strategic choices

From April 2017, water companies in England will find themselves having to compete for non-household customers. A vast amount has been achieved since the introduction of the Water Act 2014, with the development of draft market codes, the design of market systems and their interfaces, and companies making sure that they have the right data and processes in place for when the market goes live.1 The transition is ongoing, with companies now considering how to finance their retail businesses, and how best to structure contracts to cover the commercial terms with licensees.

As with the implementation of any new systems and processes, there is a risk that customers could initially experience some operational issues (such as misbilling)—an outcome that the industry is working hard to avoid. Furthermore, the water companies’ exposure to challenges under competition law will increase, as they will need to demonstrate that their wholesale trading terms to new entrants are equivalent to those offered to their own retail businesses. Breaches of competition law can carry fines of up to 10% of total group turnover, so cultural change and compliance training are going to be key.

While managing compliance with the new arrangements will be of vital importance, companies will also be thinking about their overall strategy for the retail market.

Fighting your corner

In his seminal work on competitive strategy, Professor Michael Porter posited that, in order for firms to be successful in the competitive environment, they must adopt one of three generic strategies:2

- cost leadership—being the lowest-cost company means that firms can effectively compete on price while remaining profitable (for example, Ryanair in the European airline market);

- differentiation—providing a service offering that is significantly different (and that customers value) means that firms are able to shield themselves from ‘direct competition’, as they are seen as significantly different from the rest of the industry (for example, Apple’s iPod in the MP3 player market);

- focus—focusing narrowly on a particular customer group or product segment can mean that a firm can become the best at serving its target market, and therefore remain profitable in the long run (for example, Prada in providing high-end luxury brands to affluent and fashion-conscious consumers3.

Porter considered that a failure to specialise would lead to firms ultimately losing out to those that do specialise and are therefore more proficient at meeting customers’ individual needs.

In reality, the market may be somewhat more forgiving,4 and firms may, to some extent, be able to segment their operations internally.5 However, incumbent water companies are in a fundamentally different position to firms that have always operated in competitive markets and which, out of necessity, have always targeted a particular business strategy. As water companies have been required to provide universal service within their appointed areas, they have had to adopt retail business models that broadly meet all their customers’ needs, but do not heavily specialise in meeting any particular customer need. The introduction of competition could leave them exposed to other firms that do specialise.

To an extent, similar patterns can be observed in other markets, as follows.

Since water retail competition was introduced in Scotland in 2008, the incumbent water supplier (Business Stream) has innovated, offered improved service levels, and competed fiercely on price.6 However, as stated in its annual report, it has recently seen its market share fall, and (perhaps more crucially) its margin decline.7 This may be because the company started from a position of serving the widest possible range of customers, rather than having a focused specialisation. Clear Business Water, now one of the larger new entrants in Scotland, initially gained significant market share, for example by focusing on serving SMEs rather than large users.

Similarly, in the energy retail sector, while the largest six UK energy companies remain key players, they have seen profits from non-domestic customers fall over time, with many new entrants offering specialised services.8 Ecotricity, a not-for-dividend company, invests its profits in green energy sources, for example, which appeals to environmentally conscious customers.

How to specialise?

The Water Act 2014 (following the exit regulations9 enables companies to transfer their non-household customers to one or more licensees. The UK Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) consulted on the exit regulations in summer 2015,10 and is expected to lay the regulations before Parliament in the next few months. Provided that there are no substantial changes to the regulations, companies should be able to retain one or more licensees within their overall group structure, and divest other licensees to acquiring companies.

This ‘carving up’ of the customer base will require an appropriate understanding of different customers’ preferences and attributes, as discussed in the box.

Customer segmentation in water: opportunity for improvement

The water industry’s approach to customer segmentation has not been particularly sophisticated to date. At the most recent price review in 2014, companies were required to propose customer segmentations for the purposes of setting average revenue controls. All companies chose to segment by the volumes that customers use. This led to a diverse range of customers being grouped together: a school and a nightclub might consume similar volumes of water, but may have significantly different likelihoods of default, and service preferences.

While companies will have some flexibility to offer different tariffs and service packages to customers within each average revenue control band, the current diversity of customers within each band does not aid companies in complying with competition law. For example, if the lower-cost customers within a given control band were to move away from the default tariffs (for example, by switching to a competitor), the companies would need to ensure that there was sufficient revenue available to provide a competitive margin for the remaining higher-cost customers, while complying with revenue controls that have been set based on average costs. This is not an easy task. The water companies will have an opportunity to refine their customer segmentation this year, as Ofwat’s 2014 price review set the non-household retail controls for just two years.

Having developed a detailed understanding of their existing customer base, companies will need to decide on their strategy, which includes identifying which current customers are likely to be better served by competitors, given the choice of strategy, and how to operationalise it. This could involve significant business redesign, such as forming partnerships with companies in the water sector, or from other sectors, to provide a unique combination of services.11 For example, one of the key benefits identified in the cost–benefit analysis for the Water Act 2014 was for the bundling of utility billing (such as for water and energy combined). Indeed, Severn Trent Water and United Utilities have already announced a proposed joint venture.12

The choice of retail strategy may also inform companies’ decisions on retail separation. For example, if a company were to choose a cost leadership strategy involving extensive price discounting, it would be more likely to face accusations of predatory pricing or margin squeeze. A higher degree of retail separation may therefore be useful in implementing such a strategy while demonstrating competition compliance.

Is specialisation the only option?

In short: no, other options are available.

Incumbents could seek to divest their non-household retail functions in their entirety (for example, in January 2016 Portsmouth Water announced plans to transfer its non-household retail customers to Castle Water13. Operating in the non-household retail market will carry different types of risk to the rest of water companies’ functions (for example, current investors may not have the appetite for retail market risks), and effective competition will require staff to have somewhat different skill sets to staff elsewhere in the business. Leaving the market altogether (and therefore focusing on wholesale and household retail operations) could be a sensible approach.

Remaining in the market and not specialising could also be a legitimate strategy. While the Scottish water and non-domestic energy sectors have seen margins reduce in recent years, the incumbents have still remained profitable (and, in the case of Scotland, Business Stream may be able to substantially expand its customer base following the opening of the English market). Furthermore, the customers that an incumbent retains may be particularly loyal, and therefore attractive to serve (for example, due to having potentially low default risk).

There is also the question of how a decision to divest non-household retail activities would align with companies’ broader corporate strategies. For example, if a company had a corporate strategy of increasing customer focus and understanding customer preferences, it might find this more challenging to achieve (although not insurmountable) if it divested the primary customer interface for a substantial part of its customer base. There are also a number of uncertainties at present regarding the development of upstream markets and the potential introduction of household retail competition. Companies may wish to wait to gain further clarity of these markets before making significant structural changes.

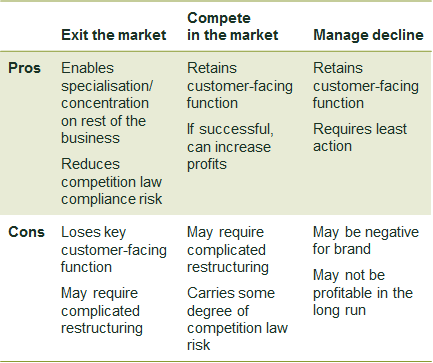

Even where companies choose to adopt strategies that do not involve fiercely competing in the market, they may need to undertake further customer segmentation analysis. From a competition law compliance perspective (see the box above), and/or if they were choosing to divest their non-household retail functions, they might gain greater value by selling parts of their customer book to different buyers. The options are compared in Table 1.

Table 1 Options for water companies

Source: Oxera.

Concluding observations

The opening of the non-household retail market in the English water sector will present companies with a series of strategic choices that incumbent companies have not had to make before.

Porter’s generic strategy framework is one way of considering the approaches that companies could adopt in the nascent market. It suggests that companies will need to fundamentally change their businesses, divest their non-household retail activities, or risk seeing their market shares and margins erode over time.

There is no one ‘right’ strategy, and companies will need to reach decisions about the best approach for them given their particular context, bearing in mind shareholder expectations. Irrespective of other changes, companies will benefit from undertaking further work on customer segmentation—and we expect this to be a major area of focus in the industry over the next few years.

1 See Open Water (2015), ‘MAP 3 technical appendices published’.

2 Porter, M.E. (2004), Competitive Strategy, Free Press Export.

3 A focus strategy does not need to be targeted towards high-end consumers; firms could target any customer segment.

4 Particularly if there are any barriers to competition, such as high barriers to entry. However, there is little to suggest that this is the case for the non-household water retail market in England, especially given the precedent observed in Scotland, where competition was introduced into this market in 2008.

5 For example, by having different brands that pursue different business models within an overall group structure.

6 Water Industry Commission for Scotland (2013), ‘Water and sewerage services in Scotland: An overview of the competitive market’.

7 Scottish Water (2015), ‘Annual Report and Accounts 2014/15’, pp. 10 and 23.

8 Ofgem (2014), ‘The revenues, costs and profits of the large energy companies in 2013’. Other factors can affect profitability, such as wholesale price movements relative to companies’ hedging strategies. Furthermore, the energy market investigation by the UK Competition and Markets Authority found differences in profitability across customer segments. See Competition and Markets Authority (2015), ‘Energy market investigation: Summary of provisional findings report’, 7 July.

9 Secondary legislation that allows incumbents to exit the market.

10 Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2015), ‘Consultation on Draft Regulations: the Water and Sewerage Undertakers (Exit from Non-household Retail Market) Regulations’.

11 See Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2011), ‘Introducing Retail Competition in the Water Sector’, impact assessment, Defra 1346.

12 Severn Trent (2016), ‘Severn Trent forms joint venture with United Utilities’, press release, 1 March; United Utilities (2016), ‘United Utilities announces joint venture with Severn Trent Water’, press release, 1 March.

13 Portsmouth Water (2016), ‘Portsmouth Water announces partnership with Castle Water to provide retail services to business customers’, press release, 25 January.

Download

Related

Ofgem’s RIIO-3 Sector Specific Methodology Decision

On 18 July 2024, Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Decision (SSMD) for the forthcoming RIIO-3 price control period for electricity transmission (ET), gas transmission (GT) and gas distribution (GD) networks.1 This follows Ofgem’s consultation on the matter in December 2023.2 RIIO-3 will last for… Read More

The future funding of the England & Wales water sector: Ofwat’s draft determinations

On Thursday 11 July, Ofwat (the England and Wales water regulator) published its much anticipated Draft Determinations (DDs). As part of the PR24 price review, this sets out its provisional assessment of allowed revenues and performance targets for AMP8 (2025–30)—and will be of great interest to water companies, investors,… Read More