The costs and benefits of measuring the costs and benefits of competition policy

Competition authorities around the world place great emphasis on measuring the effects of competition enforcement. In part, this is to justify to the public, and policymakers, that competition policy is desirable from a social welfare perspective. But are there costs as well as benefits to trying to measure the costs and benefits of competition policy interventions?

Carrying out a cost–benefit analysis (CBA) or regulatory impact assessment is generally good policy practice, and is increasingly required from policymakers and regulatory authorities around the world. In competition law, CBA can be applied to specific interventions and remedies, or to the competition regime itself. A thorough ex ante appraisal, estimating the expected costs and benefits of a proposed intervention, enables better-evidenced policy decisions (e.g. more effective remedy design). An ex post evaluation of the actual effects of past remedies allows lessons to be learned for future actions.

There is an additional reason why measuring costs and benefits is important for competition policy. There has been a spectacular proliferation of competition law globally. Awareness of competition policy has probably never been so widespread among businesses and the public at large. This proliferation, combined with high fines and competition authorities taking an increasingly proactive stance, is bound to lead to questions as well: are all these interventions justified? Competition policy needs a robust answer when it is held to account in this way. This is where the measurement of the effects of competition enforcement comes in. Various national competition authorities undertake such measurement exercises from time to time.1 The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has issued guidance for competition authorities on how to conduct these exercises and present their results.2

How to measure: identifying the counterfactual

An important initial step is to identify the objective of the CBA and to be clear about the counterfactual against which costs and benefits must be measured. CBAs can be applied to remedies in individual competition cases (both ex ante and ex post), or to the competition regime more broadly. One distinction is between the costs and benefits of competition legislation and those of the competition authority. Both are relevant but distinct policy questions.

To take the example of the Netherlands, a CBA could be undertaken for the Competition Law 1998. The relevant counterfactual for this analysis would be a situation in which the Competition Law was not enacted and the national competition authority (now the Authority for Consumers and Markets, ACM) had not been created. This would basically be the situation pre-1998 when the previous Economic Competition Law 1956 was in place, enforced by the Ministry of Economic Affairs—a regime that was generally considered inactive (the Netherlands used to be regarded as a ‘cartel paradise’).

In this counterfactual, some reliance might be placed on interventions by the European Commission under the EU competition rules, which would come into play in the counterfactual without the 1998 law. (In other words, the CBA of a national competition authority should consider only those cases that the European Commission would not cover, or would cover less well).

A separate CBA can be conducted for the competition authority itself. The counterfactual is one with a competition law in place but without a competition authority enforcing it.3 Thus, the costs and benefits of, say, the ACM would be assessed against a situation in which the Competition Law 1998 was not enforced by the authority, but rather through private litigation. A relevant question to ask in such an analysis would be: what types of anticompetitive conduct can effectively be addressed through private actions in courts, in the absence of a competition authority? Many business-to-business disputes involving restrictive agreements or abuse of dominance probably can. The costs and benefits of these should then not be ascribed to the competition authority.

A further distinction can be made between the costs and benefits of the competition authority and those of specific decisions and remedies. For the former, the absence of the authority is the counterfactual. For the latter, the authority is assumed to be in place, and the incremental analysis refers to the costs and benefits that are attributable to the enforcement action or remedy in question. The analysis can be applied to individual decisions or to a cumulative set of decisions (such as all merger decisions, or all abuse of dominance decisions). For individual decisions the analysis can be applied ex ante (i.e. as part of the decision-making process) or ex post.

What to measure: categories of costs and benefits

The next question is what costs and benefits should be included in the analysis, and how they should be weighed. At a superficial level you can do a very simple calculation: the substantial fines imposed by competition authorities in recent years are orders of magnitude higher than their annual budgets. Take the European Commission’s figures for 2013: it imposed fines of €1.7bn on banks for fixing euro and yen interest rate derivatives, and €561m on Microsoft for failing to comply with its commitments to offer users a browser choice screen, enabling them to easily choose their preferred web browser.4 These fines alone far outweigh DG Competition’s operating expenditure for 2013, which was just short of €400m.5 In one sense, therefore, it might be claimed that through its cartel and Microsoft actions alone, DG Competition has already provided substantially greater benefits to EU taxpayers than it has cost them.6

However, this comparison is not quite right: an important guiding principle is that any CBA should be performed from a total economic welfare perspective. This means that costs and benefits to all the various participants in the economy—consumers, producers, government, taxpayers—should be included in the calculations. Money transfers between different participants—such as a fine paid by a company to the competition authority (or state treasurer)—are not a net benefit to the economy. However, if considered appropriate from a policy perspective, different weights can be given to different groups—for example, consumer welfare may (implicitly or explicitly) be given greater weight than producer welfare, or poor consumers may be given greater weight than rich ones.

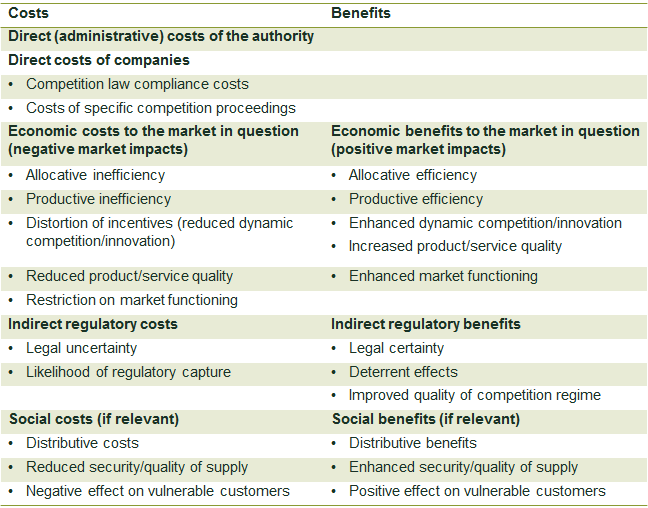

Table 1 gives an overview of the main categories of costs and benefits in a CBA. These same categories are of relevance to any policy question—i.e. whether the CBA refers to competition legislation, the competition authority, or specific enforcement actions and remedies. The main difference will lie in the counterfactual against which the categories of costs and benefits are measured. For example, to assess the costs and benefits of the competition authority, the category of ‘direct costs of the authority’ needs to cover its entire budget. To assess a specific remedy imposed by that authority, the category covers only the costs incurred by the authority in relation to that decision. (Note that the table does not include income from fines as a direct benefit of the authority, for the reason set out above.) The economic benefits of competition and (where this is the appropriate counterfactual) competition law enforcement can be measured in terms of productive and allocative efficiency, enhanced dynamic competition, enhanced market functioning, and wider effects on other sectors in the economy.

As to the category of economic costs (negative market impacts), while the objective of competition policy is to improve market functioning, actions by competition authorities can have (unintended) adverse consequences for the market as well. One indirect benefit that competition law may generate is making interventions consistent and providing clear guidance such that regulatory certainty among businesses is enhanced.

Table 1 Main categories of costs and benefits to be assessed in the CBA

When to stop measuring: precision and priorities

The economics literature has developed a range of quantitative techniques that can be applied in CBA.7 Quantitative analysis should be undertaken where feasible in order to obtain robust results, but this analysis should establish rough orders of magnitude of the various costs and benefits, rather than seek (often spurious) precision in the calculation.8 The optimal degree of quantification of the costs and benefits will depend on the circumstances. Not all costs and benefits can be readily quantified, either because of a lack of data or because the effects depend on various indirect economic interactions that are difficult to measure. Nevertheless, in practice, the assessment of rough orders of magnitude might be sufficient to gain insight into the costs and benefits of the decision or remedy in question.

In a CBA, one can often conclude that the consumer welfare benefits of intervening in price-fixing cartel cases—focusing on the total cartel overcharge paid by consumers—will be so great that they exceed the direct costs incurred by the competition authority by various orders of magnitude. Studies have shown that rough estimates of the direct benefits of enforcement actions against cartels far outweigh the estimates of the total costs of that enforcement.9 The additional indirect benefits of the interventions—in particular, the enhancement of dynamic competition and the deterrent effects on other cartels—can be described in qualitative terms because they work in the same direction and thus would reinforce the conclusion.

One tentative policy conclusion that follows is that there is merit in giving priority to cartel enforcement in larger markets, as there the welfare benefits will be greatest. However, a qualification to this conclusion is that intervention against cartels in smaller markets can still fulfil an important signalling function. A handful of such actions in smaller markets might achieve a deterrent effect. Another reasonable conclusion is that if the objective of measuring costs and benefits is to show that competition policy benefits the economy as a whole, the case can be made based only on rough approximations of the benefits of the actions against cartels.

The above approach to assessing the benefits of cartel actions cannot be readily applied to mergers, agreements other than cartels, or unilateral conduct. Remedial actions against these other practices are not as unambiguously beneficial as actions against cartels. They usually produce some efficiency benefits as well as anticompetitive effects, so intervention by the authorities can lead to negative market impacts. The extent to which a competition authority is able to strike the right balance between these two effects will depend on the quality of the underlying analysis in its investigations, and will inherently involve a degree of judgement. The extent to which market forces can be trusted depends on the views of policymakers and competition authorities, and on whether they consider it more desirable to avoid false positives or false negatives (false positives result in over-enforcement; false negatives in under-enforcement).

A specific action against a merger or business practice can therefore not automatically be presumed to be beneficial to social welfare. Indeed, CBA of a merger or abuse of dominance case runs the risk of becoming circular if it starts from the premise that the intervention is beneficial. The OECD guidance to competition authorities actually engenders the problem of circularity, by recommending that authorities should assume that their interventions are always beneficial:

No agency would intervene to block a merger or stop a business practice if it considered that its decision would not generate any benefits for consumers. Hence, it can be assumed that all the authority’s decisions will have a positive impact.10

An example of such circularity in practice can be found in an analysis by the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) in the UK (predecessor to the Competition and Markets Authority) of the effects of intervention against predatory pricing.11 In this CBA, the welfare loss of predation (and hence welfare benefit of intervention) was taken as the net present value (NPV) of the low prices to consumers during the predation period (treated as a consumer welfare gain) and the high prices during the subsequent ‘recoupment’ period (treated as a consumer welfare loss). In calculating this, the OFT effectively assumed that, first, recoupment was indeed going to be feasible, and second, predation was about to become successful at the point of OFT intervention (i.e. the predator would switch from low to high prices at that point). However, these are precisely the factors that make analysing predatory pricing cases so complex.

Concluding remarks

Should a formal ex ante CBA be required for every competition enforcement action? This policy question would perhaps merit a CBA of its own. Too formal a requirement on competition authorities could make competition law enforcement more like some other policy areas where the possible effects of interventions are argued over for a long time. The general lesson for competition law is that both ex ante and ex post CBAs can be useful policy tools that help competition authorities develop their thinking about competition problems and how to solve them. Not all costs and benefits need to be quantified with precision; indeed, false precision should be avoided.

Another policy question is who should carry out the CBA: the competition authority itself, or an independent third party? Ex post evaluations of enforcement decisions are often carried out by the authorities themselves, which, as such, is good practice in terms of learning from experience. However, in some cases an independent review may be desirable to avoid possible confirmation biases. Circular assumptions—such as that the intervention always has a positive effect—should be avoided where possible, whether in a self-assessment by a competition authority or an independent review.

1 For example, Belgian Competition Authority (2016), ‘Jaarverslag (annual report) 2015’, 24 June; and Competition and Markets Authority (2016), ‘CMA impact assessment 2015/16’, 14 July.

2 OECD (2014), ‘Guide for helping competition authorities assess the expected impact of their activities’, April.

3 The reverse situation—a competition authority without a competition law—seems less plausible. Yet this was the situation in Jersey for some time. The Jersey Competition Regulatory Authority (JCRA) was set up in 2001, but the Competition (Jersey) Law did not come into force until 2005. (In the intervening period, the JCRA did have certain regulatory responsibilities in the telecoms sector.)

4 European Commission (2013), ‘Antitrust: Commission fines banks € 1.71 billion for participating in cartels in the interest rate derivatives industry’, press release, 4 December 2013; and Microsoft (Tying) (Case COMP/39.530), Decision of 6 March 2013.

5 Figure from ‘DG Competition Annual Activity Report 2013’, Annex 3.

6 Assuming that the proceeds from the fines do indeed ultimately flow to taxpayers. It is not clear how realistic this assumption is.

7 See, for example, Boardman, A.E., Greenberg, D.H., Vining, A.R. and Weimer, D.L. (2010), Cost–Benefit Analysis: Concepts and Practice, 4th edn, Prentice Hall.

8 Manski (2013) provides a sound health warning on the limitations of CBA in an uncertain world. Manski, C.F. (2013), Public Policy in an Uncertain World: Analysis and Decisions, Harvard University Press.

9 For example, Baker, J. (2003), ‘The Case for Antitrust Enforcement’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17:4, pp. 27–50.

10 OECD (2014), ‘Guide for helping competition authorities assess the expected impact of their activities’, April, p. 2.

11 Office of Fair Trading (2005), ‘Positive Impact: An Initial Evaluation of the Effect of the Competition Enforcement Work Conducted by the OFT’, December.

Download

Contact

Dr Gunnar Niels

Managing PartnerContributor

Related

Download

Related

Ofgem’s RIIO-3 Sector Specific Methodology Decision

On 18 July 2024, Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Decision (SSMD) for the forthcoming RIIO-3 price control period for electricity transmission (ET), gas transmission (GT) and gas distribution (GD) networks.1 This follows Ofgem’s consultation on the matter in December 2023.2 RIIO-3 will last for… Read More

The future funding of the England & Wales water sector: Ofwat’s draft determinations

On Thursday 11 July, Ofwat (the England and Wales water regulator) published its much anticipated Draft Determinations (DDs). As part of the PR24 price review, this sets out its provisional assessment of allowed revenues and performance targets for AMP8 (2025–30)—and will be of great interest to water companies, investors,… Read More