The CMA’s determinations for Bristol Water: an appealing process?

In 2014, Ofwat published its price determinations for the period covering 2015–20. Of the 19 water companies,[1] 18 accepted their determinations, while Bristol did not. In March 2015, Ofwat referred this determination to the CMA,[2] which published its final findings in October 2015.[3]

Ofwat’s final determination was significantly different from Bristol’s business plan. Bristol’s plan was for average annual household bills to fall by 6% to £187 by 2020, whereas the final determinations required a 19% decrease, to £155. The CMA’s determination resulted in bills being reduced by 16% by 2020, to £160.[4] While this appears to be closer to Ofwat’s position than to Bristol’s, it masks other aspects of the CMA’s determination, such as a reduced scope for an increased allowed spend.

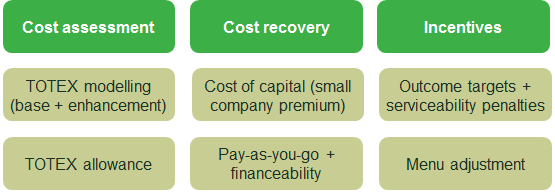

This article focuses on the key areas of dispute, and how the CMA reached its conclusions. At the 2014 review, for the first time, Ofwat set separate price controls for wholesale, household retail, and non-household retail services. Bristol appealed its wholesale control only. However, Ofwat referred all three controls to the CMA for review. The CMA chose not to review the retail controls as they made up a relatively small part of Bristol’s overall revenue allowance, and no party had raised material concerns. The key issues that Bristol appealed are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Key issues appealed

Source: Oxera analysis of CMA (2015).

Cost assessment

In arriving at its assessment of the appropriate level of costs that Bristol should incur, Ofwat relied heavily on TOTEX efficiency models. These econometric models, newly developed for PR14, combined operating expenditure (OPEX) and capital expenditure (CAPEX), considered both business plan and historical data, and covered both base expenditure (BOTEX, or base OPEX plus capital maintenance expenditure) and enhancement spend.[5] Ofwat also allowed for a series of adjustments to be made for specific aspects of the company’s operational characteristics and circumstances that were not adequately reflected in the TOTEX models.

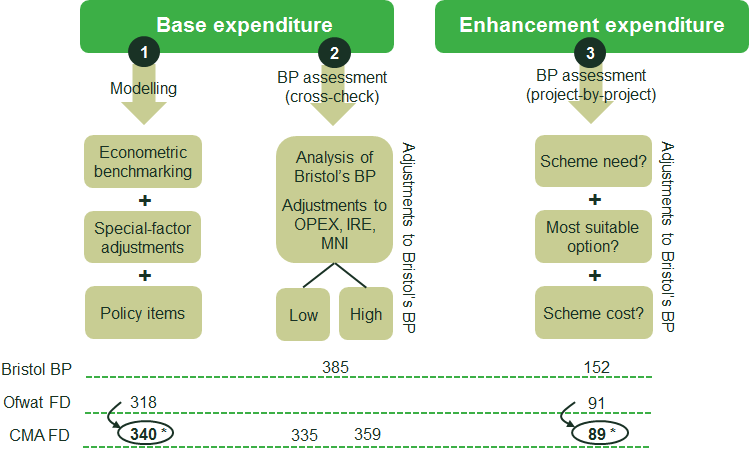

Figure 2 illustrates the CMA’s approach to cost assessment. In addition, it presents the CMA’s final determination allowance and compares this to Bristol’s business plan (BP) and Ofwat’s final determination (FD). As part of its cost assessment approach, the CMA decided to develop its own BOTEX models (process 1 in the figure). As a cross-check, the CMA also carried out a targeted review of BOTEX in Bristol’s business plan, applying adjustments that it considered necessary (process 2 in the figure). The CMA rejected outright Ofwat’s top-down modelling of enhancement spend—instead favouring a bottom-up assessment on a scheme-by-scheme basis (process 3 in the figure).

Figure 2 CMA approach to determining TOTEX (figures in £m)

Source: Oxera analysis. CMA Final Determination and Ofwat Final Determination figures are from CMA (2015), pp. 9, 12, 129, 132, 186.

Taken together, these interventions increased Bristol’s cost allowance from £409m[6] to £429m (£340m + £89m), for a reduced scope of work on the enhancement side.

A look at the econometrics

Focusing first on the econometrics, the CMA highlighted a number of concerns with Ofwat’s approach, as follows—which are closely aligned with concerns raised by Bristol. Some of the ways in which Ofwat might subsequently take these issues into account are also set out below, following its publication during the case of a Water 2020 paper on cost assessment issues.[7]

-

Robustness and interpretability of the econometric models. The CMA argued that Ofwat’s models included a large number of explanatory variables, resulting in spurious correlations between cost drivers. Moreover, the CMA argued that Ofwat’s models lacked transparency[8] and led to counterintuitive results. These considerations are important in light of Ofwat’s intention to reassess the models and determine whether and how to improve them.[9]

-

Modelling enhancement expenditure. Ofwat’s TOTEX models were not considered suitable for enhancement expenditure, as these costs differed according to local, ecological and environmental factors. Going forward, Ofwat has indicated that it will review its approach to enhancement modelling and whether and how to improve it.[10]

-

Disaggregated modelling. The CMA was concerned about the emphasis on top-down TOTEX models, and indicated that their accuracy could be improved by complementing the analysis with disaggregated analysis or a detailed review of business plans. Ofwat has expressed an interest in a more disaggregated approach to cost assessment for PR19. While the CMA assessed OPEX, MNI and IRE separately, going forward, Ofwat might review the companies’ performance over individual components of the value chain.[11]

-

Special factors. In order to capture Bristol’s specific issues, the CMA included certain variables in its econometric models (e.g. treatment variables). The CMA also voiced a more general concern about the asymmetry in the approach to special factors.[12] In this respect, Ofwat is considering some changes to its assessment of special factors in PR19—for example, whether companies should see the benchmarking models before submitting their claims; whether third parties can play a role in determining such factors; and how to avoid ‘one-way bets’ (i.e. the asymmetry of companies primarily submitting claims for cost increases due to external factors and not for cost reductions).[13]

-

Efficiency targets. According to the CMA, Ofwat’s approach of using the upper-quartile efficiency challenge may overstate inefficiency. As an alternative to Ofwat’s upper-quartile approach, the CMA used an average-efficiency benchmark, but it also assumed a cost trend of RPI – 1% per year. This ‘dynamic’ approach was intended to capture input price inflation and productivity improvements. Going forward, Ofwat is considering whether to use a more challenging benchmark, and whether benchmarks should be dynamic.[14]

As a result of its review, the CMA decided not to use Ofwat’s models. Instead, for base expenditure, it developed its own top-down BOTEX models, and as a cross-check undertook an analysis of Bristol’s business plan. In the end the CMA relied on its top-down assessment in setting allowed BOTEX (£340m, compared with Ofwat’s £318m). While the CMA’s cross-check resulted in a much higher central estimate (£347m), it concluded that:

We considered it appropriate, in assessing the efficient level of expenditure, to give more weight to the estimate that made use of industry-wide benchmarking analysis, complemented by detailed further assessment to take better account of Bristol Water’s needs and circumstances, than to estimates derived from adjustments to Bristol Water’s own expenditure forecasts.[15]

Enhancement schemes

The CMA took a different approach towards enhancement expenditure, favouring more of a bottom-up assessment. Its scheme-by-scheme approach included examination by its own engineering consultants, as well as Ofwat’s ‘deep dives’[16] into the issues. The hurdles applied were, in order, need, optioning, and cost. Two schemes of major contention were a new reservoir that Bristol had included in its plan (Cheddar 2), and a new water treatment works at Cheddar to deal with a deterioration in raw water quality.

-

Need? The construction of the Cheddar 2 reservoir was the biggest enhancement scheme proposed by Bristol, at £42.8m in 2015–20, which would have increased its regulatory capital value (RCV) by around a quarter over the five-year period. Bristol argued that the scheme was justified by need.[17] However, like Ofwat before it, the CMA disallowed any expenditure.[18] For example, while the CMA took account of the fact that the scheme was included in Bristol’s water resources management plan (WRMP), which had been approved by the Secretary of State, it did not regard itself as ‘bound’ by the WRMP. The case of Cheddar 2 shows that the CMA was willing to get into the detail and that, in its view, the question of assessing ‘need’ was within its remit.

-

Optioning? As regards the Cheddar water treatment works, Bristol had sought £21m in its business plan to deal with raw water quality deterioration. Ofwat had made an allowance in the final determination, following a deep dive, of £16.9m.[19] The scheme had the support of the Drinking Water Inspectorate (DWI). Interestingly, the CMA disallowed most of this expenditure, as it was not convinced that Bristol had identified the underlying cause of the raw water problem. Instead, a £1m allowance was made for investigative work, coupled with a Notified Item. Crucially, this means that, if the DWI at some point rules that the works are indeed required, Bristol can apply for an increase in prices so as to provide the necessary funding.

The CMA thus excluded the above two schemes—even when there was support from the government bodies concerned—and did not reach firm conclusions about whether they had been appropriately costed.[20] The remaining enhancement expenditure sought by Bristol was, for the most part, allowed for in full by the CMA. The scope of work involved was deemed necessary and, despite arguments made by Ofwat, no further top-down efficiency challenge was deemed appropriate (for example, Bristol had already applied a 12.5% efficiency challenge).

On enhancement as a whole, therefore, Bristol received slightly less funding than had been allowed for by Ofwat, but for a more significantly reduced scope of work (e.g. the exclusion of Cheddar water treatment works). Bristol has stated that, once this revised scope is taken into account, and the gains on enhancement and base expenditure are then combined, the CMA allowed for 10% more TOTEX overall.[21]

Cost recovery

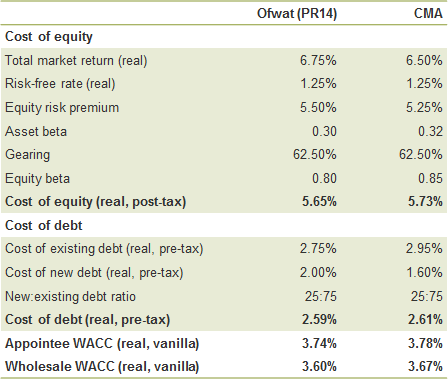

The CMA assessed the latest market data with regard to the cost of capital, and this acted as a downward driver on the cost of capital. However, unlike Ofwat, the CMA considered that Bristol (due to being a small company compared with the rest of the industry) warranted an uplift on the industry weighted average cost of capital (WACC). The net effect was a marginal increase in the cost of capital, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Bristol’s cost of capital

Source: CMA (2015), Table 10.4, and discussion in paragraphs 10.1 to 10.197.

On balance, the cost of capital increased only marginally, and the allowance made by the CMA for a ‘small company premium’ is likely to be of interest mainly to water-only companies. At PR14, while Ofwat did not rule out such an allowance in principle, since small companies may be faced with higher financing costs than larger ones, it did require companies to provide evidence that there were offsetting benefits to customers should such an adjustment be applied. Ofwat concluded that it was not beneficial to make an adjustment for most of the water-only companies.[22] However, the CMA concluded that removing the small company premium ‘ran contrary to the reasonable expectation of investors that they could, on average over time, recover the cost of efficiently incurred debt’.[23]

The CMA also concluded that Bristol would be financeable over 2015–20, supported by its financial ratios analysis. The focus was on S&P financial ratios, as these were the major concern for Bristol. A notional gearing and a target credit rating of BBB were used.

Incentives

Looking backwards, looking forwards

Looking at historical performance, the CMA upheld Ofwat’s adjustment to Bristol’s RCV in relation to Bristol underperforming on some metrics relating to the serviceability of its assets. Bristol had contended that the adjustment was not appropriate due to Ofwat having changed its methodology. The CMA considered that Ofwat (albeit with limited signposting) had given sufficient guidance around the updated methodology, and that Bristol had been in breach of its performance targets.

Looking to the future, the CMA was supportive of Ofwat’s move to focus on outcome regulation, as opposed to specifying detailed outputs such as length of main replaced. Indeed, there was broad agreement on this across the various parties as a point of principle. However, the CMA considered that assuming that ‘upper quartile performance (historical or otherwise) would match economic levels appeared unlikely’.[24] In setting Bristol’s performance targets, the CMA used customer research undertaken by Bristol, rather than setting targets at the industry’s upper-quartile level.

This may have implications for Ofwat’s methodology for PR19. The regulator is currently considering the role of comparators in determining outcomes.[25] While drawing comparisons may still play a role, given the CMA’s determination, Ofwat may wish to consider approaches that do not result in targets being directly set through comparisons.

Menu design

Another area of incentives examined by the CMA was Ofwat’s application of menu regulation. Menu regulation is used to provide companies with incentives to produce accurate expenditure forecasts: the more robust the expenditure forecasts made by the company, as assessed by the regulator, the higher the reward (or lower the penalty) the company receives (through ‘additional income’), and the more outperformance it retains once prices have been set (through the ‘cost-sharing incentive’). A third component, ‘interpolation’, determines how much weight is given to each company’s own expenditure assessment versus the regulator’s assessment in setting the allowed expenditure.[26]

Bristol argued that it was penalised unduly under the scheme. First, while it had been free to make a final menu choice after the final determinations, and had excluded Cheddar 2 as an outcome by this point, Ofwat’s PR14 price limit assumptions retained the higher prior implied menu choice that included Cheddar 2. Second, Bristol argued that the large difference between its business plan forecasts and Ofwat’s assessment of TOTEX was itself due to Ofwat’s assessment of its costs—as discussed above. Third, Ofwat had allowed for expenditure of £437m—75% based on the regulator’s own assessment and 25% on Bristol’s business plan. While this indirectly increased allowed revenue, the upfront penalty—of around £17m—was deducted directly from allowed revenue. Crucially, Ofwat did not take account of the impact of this penalty in its financeability assessment.[27]

The CMA approached the issues from a somewhat different angle, more or less starting from first principles.[28]

First, the CMA noted that Ofwat’s application of the menu was different to previous reviews (and different to that of Ofgem, the energy regulator for Great Britain). While the PR14 menu was intended, in part, to provide incentives for companies to submit accurate forecasts, Ofwat did not present this as the primary objective. Instead, the scheme prioritised allowing companies to choose the cost-sharing incentive and influence the wholesale TOTEX allowance (through the interpolation). The CMA did not, however, see why it was important for companies to have a choice of cost-sharing incentive within the range specified by Ofwat (44–55%). According to the CMA, the scheme appeared to provide limited choice in practice. Moreover, the positive long-term impact of interpolation on a company’s finances was regarded as ‘illusory’.[29]

Second, the menu did not apply to companies’ business plan forecasts, submitted some time before the final determinations. Instead, it applied to forecasts submitted by companies in January 2015, which was after the final determinations. As such, it was difficult to see how Ofwat’s menu contributed to the ‘original Ofgem objective’ of submitting more accurate business plans.[30] And while the CMA accepted Ofwat’s argument that the January 2015 menu choices might provide useful information for the next review (PR19), this was not seen as a compelling reason to retain the menu here. Ofwat had not emphasised this rationale in its PR14 documents, and it was also unclear how useful the revealed information would be for future cost assessment.

Finally, there were complications in determining how financeability should be assessed within the menu against the background of Bristol’s concerns.

The CMA therefore chose not to apply the menu scheme to Bristol in this case, while recognising that different considerations might apply to a process covering 18 companies. The wholesale cost allowance was thus set at £427m—i.e. without any 25/75% interpolation—and no upfront penalty was applied. Nonetheless, a cost-sharing incentive was retained, set at 50%.

In essence, the CMA did not question the use of menu regulation per se. Rather, it questioned Ofwat’s intended objectives for the menu in PR14, and the implementation of the scheme. Interestingly, in one of the recent electricity distribution appeals (RIIO-ED1), the CMA highlighted that, in setting a menu, retaining incentives for future price controls was a valid consideration.[31] However, the two cases are different. First, in the electricity case the CMA did not disagree with Ofgem’s stated policy intention—in that instance, to encourage accurate forecasts through rewarding upper-quartile performance.[32] Second, in electricity distribution, companies’ menu decisions were cemented prior to the final determinations. Ofgem’s concern was about incentives to submit robust forecasts at future price controls, rather than about further information revelation immediately after a price review.

Time for reflection?

Referring a price control to the CMA can be time-consuming and intensive. This is likely to be even more challenging for a small company, which would still need a dedicated team that is immersed in the inquiry aside from day-to-day business. It can also put the relationship between a company and the regulator under strain. However, if a company genuinely thinks that it cannot deliver the outcomes required of a price control for the revenues allowed, this will inevitably force its hand. These issues are likely to have been relevant in this case.

The above discussion illustrates how the CMA is prepared to drill down into the detail in order to reach its own assessment on the issues—notably, in terms of its approach to econometric modelling, enhancement schemes, and menu regulation. Things went down as well as up, and the overall outcome is a price profile closer to that proposed by Ofwat in its final determinations than that sought by Bristol. However, this somewhat masks the fact that Bristol has received more funding for a reduced scope on enhancement.

Furthermore, the CMA’s review identified issues with Ofwat’s approach to TOTEX modelling, and its objectives and approach towards menu design—which will be of wider interest to the industry in the preparatory stages of PR19.

What might the future of water inquiries hold? Unlike in the energy sector, in water there is currently no third-party appeal process in place. However, the opening of the non-household retail market from 2017[33] may lead to a greater degree of scrutiny of Ofwat’s determinations by third parties. This could (while not currently enshrined in legislation) create a similar dynamic to the electricity distribution controls.[34]

[1] There has since been a merger between South West Water and Bournemouth Water. Cholderton Water is subject to a lighter-touch review than the rest of the industry due to its size.

[2] Oxera advised Bristol Water during the CMA inquiry.

[3] Competition and Markets Authority (2015), ‘Bristol Water plc. A reference under section 12(3)(a) of the Water Industry Act 1991. Report’, October (‘CMA (2015)’).

[4] Ofwat (2015), ‘PN 03/15: Ofwat welcomes CMA’s final decision on Bristol Water’s price determination appeal’, October.

[5] One set of Ofwat’s models did consider BOTEX and enhancement separately.

[6] The Ofwat figure of £409m reflects its assessment of TOTEX, as opposed to the level assumed under the menu choice mechanism. The latter sets allowed expenditure at 75% Ofwat’s estimate and 25% the company’s estimate (sometimes referred to as ‘interpolation’). This was £437m. The menu mechanism is discussed further below.

[7] Ofwat (2015), ‘Towards Water 2020 – policy issues: regulating monopolies’, July.

[8] Ofwat’s models are in partial translog form. Partial translog regression models are more flexible as they include cross-products and squared terms. As such, the implied relationships between costs and cost drivers vary by company.

[9] Ofwat (2015), ‘Towards Water 2020 – policy issues: regulating monopolies’, July, p. 12.

[10] Ofwat (2015), ‘Towards Water 2020 – policy issues: regulating monopolies’, July, p. 12.

[11] Ofwat (2015), ‘Towards Water 2020 – policy issues: regulating monopolies’, July, p. 7.

[12] Special factors represent external factors that affect a company’s costs that are not accounted for in the cost modelling. Ofwat’s benchmarking approach, like those of other regulators, may over- or underestimate costs due to such factors. Companies make representations to Ofwat for upward adjustments for such factors, but tend not to make representations for downward adjustments. The CMA discusses the issue in CMA (2015), Appendix 3, paras 11–19.

[13] Ofwat (2015) ‘Towards Water 2020 – policy issues: regulating monopolies’, July, p. 12.

[14] Ofwat (2015) ‘Towards Water 2020 – policy issues: regulating monopolies’, July, p. 12.

[15] CMA (2015), para. 7.11.

[16] These represent adjustments that capture those aspects of companies’ business plans that are not fully provided for in Ofwat’s cost assessment.

[17] Bristol argued that the Cheddar 2 reservoir might be required to supply a new power station or to meet a supply/demand imbalance in the second half of the water resources management plan (WRMP) period. It was supported by security of supply/resilience considerations. See CMA (2015), paras 40–41 and sections 6–7.

[18] The CMA argued that it was unclear if and when the new power station would be built or that Bristol would be the preferred supplier; that a series of smaller schemes would be more appropriate to address any supply/demand imbalance issues; and that, on resilience grounds, there was insufficient evidence of an immediate need for investment or of customer willingness to pay. See CMA (2015), paras 42–43 and sections 6–7.

[19] See CMA (2015), para. 6.181.

[20] While the CMA discussed the cost of the Cheddar 2 and Cheddar water treatment works schemes, it did not conclude whether they were appropriately costed, as the two schemes had not passed the prior tests for ‘need?’ and ‘most suitable option?’. See, for example, CMA (2015), para. 6.176 and Table 7.3.

[21] For the 10% TOTEX comparison, see Bristol Water (2015), ‘Lessons to be learned from CMA’s Final Determination, says Bristol Water’, 21 October. See also Figure 2 in this article. Oxera understands from discussions with Bristol that the CMA TOTEX allowance was £429m, compared with Ofwat’s final determination TOTEX allowance of £409m, and that Bristol’s cost estimate of the Cheddar water treatment works enhancement scheme was £23m. Given the exclusion of the scheme by the CMA, deducting this £23m from Ofwat’s TOTEX allowance produces a scope-adjusted TOTEX figure of £386m. Hence the CMA’s TOTEX allowance was £43m higher than Ofwat’s scope-adjusted TOTEX allowance. This represents just over 10% more TOTEX—or, alternatively, around 10% of the CMA’s TOTEX allowance—and combines the gains on base and enhancement expenditure. When the gain on enhancement is expressed as a proportion of scope-adjusted enhancement spend only, the percentage gain is greater. Source: Bristol Water.

[22] Ofwat (2014), ‘Annex to technical appendix A6 – benefits assessment from a company-specific uplift on the cost of capital’, p. 2.

[23] CMA (2015), p. 309.

[24] CMA (2015), p. 283.

[25] Ofwat (2015), ‘Towards Water 2020 – policy issues: customer engagement and outcomes’, p. 12.

[26] The CMA does not refer to the term ‘interpolation’ in the Bristol inquiry report, but this is the commonly used terminology in the water and energy sectors.

[27] See CMA (2015), Table 11.7, for a presentation of the £17m figure, and Appendix 2.4 for a discussion of Bristol’s concerns.

[28] The CMA’s assessment of Ofwat’s menu is contained in CMA (2015), Appendix 2.4 and paras 3.52–3.55.

[29] The CMA stated that ‘the 25% weight to the company forecast has an effect on the revenues allowed during the price control period, but this effect will be offset by financial adjustments that are made, under the terms of the scheme, in future price control periods. In net present value terms, and using the same discount rate as Ofwat applies to implement the scheme, the overall effect of the 25% weighting to the company’s forecast is zero’. See CMA (2015), Appendix 2.4, para. 11.

[30] CMA (2015), Appendix 2.4, para. 55.

[31] See Oxera (2015), ‘Electricity distribution: the CMA decides’, Agenda, October.

[32] However, the CMA argued that the way in which Ofgem had adjusted its calibration of the Information Quality Incentive was inconsistent with its stated upper-quartile objective. See Oxera (2015), ‘Electricity distribution: the CMA decides’, Agenda, October.

[33] Open Water (2015), ‘The Open Water programme: Stakeholder update’.

[34] The scope of review, and standard of proof, differ between the water and electricity distribution sectors. See Oxera (2015), ‘Electricity distribution: the CMA decides’, Agenda, October.

Download

Related

Time to get real about hydrogen (and the regulatory tools to do so)

It’s ‘time for a reality check’ on the realistic prospects of progress towards the EU’s ambitious hydrogen goals, according to the European Court of Auditors’ (ECA) evaluation of the EU’s renewable hydrogen strategy.1 The same message is echoed in some recent assessments within member states, for example by… Read More

Financing the green transition: can private capital bridge the gap?

The green transition isn’t just about switching from fossil fuels to renewable or zero-carbon sources—it also requires smarter, more efficient use of energy. By harnessing technology, improving energy efficiency, and generating power closer to where it’s consumed, we can cut both costs and carbon emissions. In this episode of Top… Read More