Ofwat’s PR19 methodology: what’s changed?

On 13 December 2017, Ofwat published its final methodology for how it will set prices at the next price review (PR19).1 The document spans over 250 pages. What then are the new messages and changes relative to the regulator’s draft methodology, set out in July 20172 (discussed in a previous issue of Agenda)?3

Overall, the message remains the same: it’s going to be a tougher price control than before (at PR14). Many of the decisions remain the same as those set out in July; however, there have been some changes. In what follows, we focus on the areas in which there have been the most movement: incentives, efficiency, finance and the form of control.

Incentives

In PR19 companies need to agree performance commitments (PCs) and outcome delivery incentives (ODIs) with their customers. Some of these are company-specific, while others will be common across companies. On PCs and ODIs, the key changes since July are as follows.

- For three of the 14 common PCs (water supply interruptions, internal sewer flooding, and pollution incidents), companies will set their commitments at least at the forecast performance level of the upper quartile (UQ) of companies as measured in each year (rather than achieving from 2020–21 what will be the UQ in 2024/25, as per the draft methodology—something that companies disagreed with).

- Ofwat will require all companies to reduce leakage by 15% over the five years.

- Ofwat has confirmed the four PCs relating to asset health: mains bursts, unplanned outages, sewer collapse, and treatment work compliance.

- There is a new requirement for companies to develop a bespoke PC to manage ‘voids’ and ‘gap sites’ (see the discussion of the retail form of control, below).

- Ofwat has confirmed the indicative range for the overall value of ODIs of +/-1% to +/-3%.

- Ofwat has confirmed that it wants companies to consider financial ODIs as a default position. If companies do not propose financial ODIs, they must justify and provide supporting evidence to explain why this is not the case.

As such, there has been some movement, most notably in relation to the UQ challenge.

Securing cost efficiency

Key to setting prices is the setting of efficiency targets, which are applied to company expenditure. While the focus of the regime is on total expenditure (TOTEX), the efficiency analysis does make distinctions between base TOTEX (BOTEX) and enhancement TOTEX. The main changes to setting wholesale cost-efficiency targets since July are as follows.

- Ofwat’s focus now seems to be more on base costs (BOTEX), with enhancement expenditure included where this is possible.

- For unconfirmed environmental requirements, Ofwat will fund the anticipated programme as long as companies suggest an adjustment mechanism based on outcomes and unit costs.

- Ofwat has increased its materiality thresholds for special cost factor claims. While the symmetric approach remains (i.e. applying both positive and negative adjustments), negative adjustments will now be made on a case-by-case basis.

- Compared with the proposed cost-sharing incentive, companies with efficient plans will keep a greater share of cost outperformance, and those with inefficient plans will keep a lower proportion. Ofwat has also set the underperformance incentive rate flat at 50% for business plans that are more ambitious than their view of efficient TOTEX.

- On cash flows, Ofwat will now set the cost allowance equal to its view, with reconciliation made at the end of the five-year period. This option provides more (less) cash during the period for efficient (inefficient) companies.

Therefore, there has been some movement since July, but the overall framework remains largely unchanged.

Aligning risk and return

In the water sector, Ofwat employs a two-stage approach to allowing companies financing costs. First, it sets the cost of capital in order to determine the returns required by investors (using a ‘building block’ approach). Second, through exploring various indicators, the regulator checks whether the package as a whole is financeable. In practice, allowed returns (contained within price limits, and outturn returns once prices are set) also depend on the incentives put into place (e.g. for ‘fast tracking’).

The main changes since the July consultation are as follows.

- The companies commented that the financial incentives might not be strong enough for them to target fast-track and exceptional categories of business planning. Reflecting this feedback, Ofwat has increased the reward for exceptional business plans to a range of 0.20–0.35% of return on regulated equity (RORE) and introduced a reward for fast-track business plans of 0.10% of RORE.

- Ofwat’s approach to risk and rewards means that there will be higher potential downside for companies in the significant scrutiny category; more rewards for other companies; more significant penalties for poor delivery; i.e. more dispersion of returns across the industry.

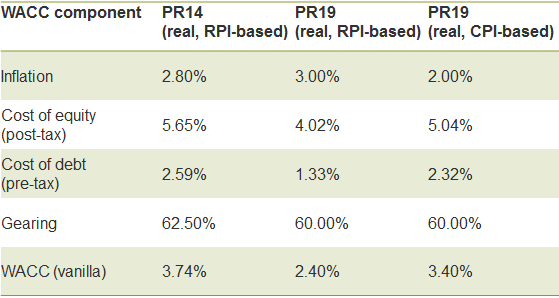

- There is a significant reduction in the allowed weighted average cost of capital (WACC) from the last price control, especially when comparing the number on a like-for-like RPI basis. Ofwat’s WACC estimates of 2.40% (real, RPI-based) and 3.40% (real, CPI-based) are 1.33 and 0.33 percentage points lower than the PR14 estimate of 3.74%.

- Ofwat is now explicitly saying that it assumes a negative real risk-free rate, which affects a number of other WACC parameters.

- Ofwat considers that there is a lot of evidence indicating that future equity returns are likely to be lower than historical ones. Therefore, relying too much on long-term historical data could result in an overstatement of the WACC. Ofwat states that it has relied on both the historical and forward-looking data and that this is in line with its approach adopted in past decisions (e.g. at PR09).

- Ofwat did not accept that smaller companies have higher risk and should earn higher returns. If companies have higher financing costs than a notionally efficient company, then this would need to be offset by benefits to customers, i.e. the customer benefit test will still be in place despite the Competition and Markets Authority’s decision on Bristol Water’s appeal.[4]

- Ofwat’s approach on financeability is broadly similar to that adopted at PR14. In addition, Ofwat will conduct assessments on separate controls as a cross-check against its assessment at the appointee level. Companies will be required to consider impacts on bills for AMP7 and beyond when proposing to use any of the financeability levers available to them.

The significant reduction in the WACC since PR14 is a particularly significant development. Despite real yields on 10-year UK government bonds tracking below zero since September 2011, Ofwat is the first UK economic regulator to explicitly adopt a negative real risk-free rate when estimating the cost of capital. Ofwat’s methodology may indicate a shift in the thinking of regulatory authorities regarding the risk-free rate—zero is evidently no longer the lower bound.

Table 1 Ofwat’s view of the cost of capital

Form of control

In PR14, Ofwat set separate price controls for retail and wholesale—partly in preparation for market opening in the business retail sector (which occurred in April 2017).5 In PR19, Ofwat will be further disaggregating the wholesale controls into the monopoly elements (‘network-plus’) and potentially contestable areas in the upstream value chain—water resources on the clean water side and bioresources on the wastewater side.

In July, Ofwat set out how this growing number of price controls would function—i.e. the ‘form of control’ for household retail, business retail, water network-plus, wastewater network-plus, water resources and bioresources.

On retail, developments since the July document are as follows.

- The July document looked at the possibility of three-year controls for both households and non-households. This would allow the impact of the lessons from market opening to be taken into account. However, Ofwat has since stated that it is unlikely that the benefits would exceed the costs (the burden).

- The household control will therefore be five years (with no re-opener provision, as this would lead to a similar undue burden plus changes to each company’s licence, which may be difficult to get agreement on in practice).

- The non-household control for non-exiting companies will also be for five years. More clarity is provided on the average revenue control proposed in July. For customers using five Ml/year or less this will be based on a cost to serve and net margin approach (as used in the 2016 review of non-household retail). Larger customers will then be subject to a gross margin cap.

- Ofwat has confirmed that there will be no non-household retail control for companies that have exited the market (as noted in July, instead the retail exit code and competition law will apply).

- The final methodology requires an additional requirement for companies to put forward bespoke PCs, covering the management of site gaps (unbilled properties) and voids (vacant properties), for both household and non-household customers.

On water resources, changes since July are as follows.

- Utilisation risk through network access. In July, Ofwat noted that a revenue adjustment mechanism (using yield as a measure of capacity) would apply if the bilateral market opens over the 2020–25 period. Ofwat now anticipates that a small initial bilateral market could open in 2022. Access pricing reporting requirements for English companies have been streamlined.

- Utilisation risk from general market-wide demand risk. In July, Ofwat mentioned that any firm proposing large-scale investment in resources over the longer term would need to propose risk-sharing in the event of under-utilisation. In the December document, Ofwat has left it to companies to propose adjustment mechanisms (including the appropriate use of deadbands), but has also set out a guiding set of principles that it will use to assess companies’ proposals.

On bioresources, changes since July are as follows.

- The average revenue control proposed in July (based on a revenue per tonne of dried solid) has since been modified to protect customers. Ofwat notes that there are economies of scale in treating sludge, such that average costs fall as volumes increase. Under a pure average control the same average cost would be funded through revenues regardless of actual sludge volumes processed. Companies would earn windfall profits if volumes were greater than forecast. Ofwat has proposed an adjustment mechanism to the average revenue control. When measured volumes vary from forecasts, the adjustments to allowed revenues are based on the increment, rather than the average.

- The sludge forecasting accuracy incentive proposed in July had a deadband of +/-3% (with revenue return where variations > 7%). In light of company responses and the additional customer protection provided by the above adjustment mechanism to the average revenue control, Ofwat has changed position. Namely, it has increased the deadband from 3% to 6% and modified the penalty rate.

As such there have been some important tweaks to the various controls since July, most notably on the retail side.

Moving forward…

The December methodology puts a stake in the ground in terms of where Ofwat’s thinking lies on key issues and the challenge ahead for the companies. The initial WACC estimate, in particular, points to a tightening of expected returns. While PR19 will be tough it also offers incentives to earn additional rewards for companies (those who put forward robust business plans, and who can demonstrate leading performance on cost efficiency and outcomes).

In addition to the technical changes since July discussed above, it is also worth noting that there will be a handing-on of the baton going forward. The current Chief Executive, Cathryn Ross, who has led the price review to date, will be leaving (to take up an executive position at BT). Rachel Fletcher, who is currently Senior Partner for Consumers and Competition at Ofgem (and Board member), will join Ofwat in the New Year.6

2018 will not be an easy year for companies. However, the PR19 process provides an opportunity to demonstrate innovative thinking on issues such as customer engagement, resilience, helping vulnerable customers and making best use of customer data. Companies need to do so within the framework discussed above.

1 Ofwat (2017), ‘Delivering Water 2020: Our final methodology for the 2019 price review’, December.

2 Ofwat (2017), ‘Delivering Water 2020: Consulting on our methodology for the 2019 price review’, July.

3 Oxera (2017), ‘It’s a tough one: Ofwat’s PR19 methodology’, Agenda, September.

4 Oxera (2015), ‘The CMA’s determinations for Bristol Water: an appealing process?, Agenda, December.

5 Oxera (2017), ‘Time to choose: retail market opening in the water sector’, Agenda, March.

6 Ofwat (2017), ‘PN 31/17: Ofwat announces appointment of new Chief Executive’, December.

Download

Related

Ofgem’s RIIO-3 Sector Specific Methodology Decision

On 18 July 2024, Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Decision (SSMD) for the forthcoming RIIO-3 price control period for electricity transmission (ET), gas transmission (GT) and gas distribution (GD) networks.1 This follows Ofgem’s consultation on the matter in December 2023.2 RIIO-3 will last for… Read More

The future funding of the England & Wales water sector: Ofwat’s draft determinations

On Thursday 11 July, Ofwat (the England and Wales water regulator) published its much anticipated Draft Determinations (DDs). As part of the PR24 price review, this sets out its provisional assessment of allowed revenues and performance targets for AMP8 (2025–30)—and will be of great interest to water companies, investors,… Read More