Malbeconomics: taking stock of the 20th anniversary of the 9.99 price point

Developed economies are facing significant amounts of inflation for the first time in 25 years. Consumer prices, measured according to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), rose by 5.8% on average across OECD countries in the year to November 2021. Will Page, former Chief Economist at Spotify and author of Tarzan Economics, celebrates the 20th anniversary of the 9.99 price point and looks at the role that price points play in an inflationary environment.

Twenty years ago this month, the floodgates of on-demand music burst open. As pundits questioned whether fans would pay for recently launched services such as Rhapsody and Real Networks, America Online (now ‘Aol.’) and a joint venture between Sony and Vivendi joined the fray. Each offered customers varying menus of song downloads and streams, and all charged a monthly fee of just $9.99—still the dominant price in US dollars, euros and pounds sterling.1

The origins of this 9.99 price point are disputed. Some allude to the ‘charm-pricing’ technique purporting that bills ending in ‘99’ feel more than one cent cheaper than the next integer. Others say the number was set to mirror the cost of a Blockbuster rental card. Whatever its true genesis, the two-decades-old 9.99 price point is the missing note in the ongoing chorus of debate about how much music is worth and what it should cost.

The UK price isn’t right

Transatlantic price comparisons matter—and over in the UK, it’s getting political.

A Parliamentary inquiry that kicked off late last year has led to the prospect of Britain’s competition and intellectual property regulators, including the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA),2 upending the economics of music streaming in an attempt to more fairly reward performers and creators.3 Worryingly, given the divisive nature of the year-long debate about music streaming economics, a constructive conversation about something as important as price has been lacking throughout the process.

Britain was late to the streaming party, but early to adopt it en masse—with Spotify launching its £9.99 offering there in February 2009,4 almost a decade after the US services landed on the late Netscape browser. Spotify’s eurozone rollout came soon after—again at €9.99—with the long-awaited US launch following in July 2011 at (you guessed it) $9.99.5

A stable price point of 9.99 has benefits for consumers: all else being equal, as incomes rise, more listeners should be willing to pay a fixed fee. However, it also comes with inflationary costs—especially for the artists and songwriters.

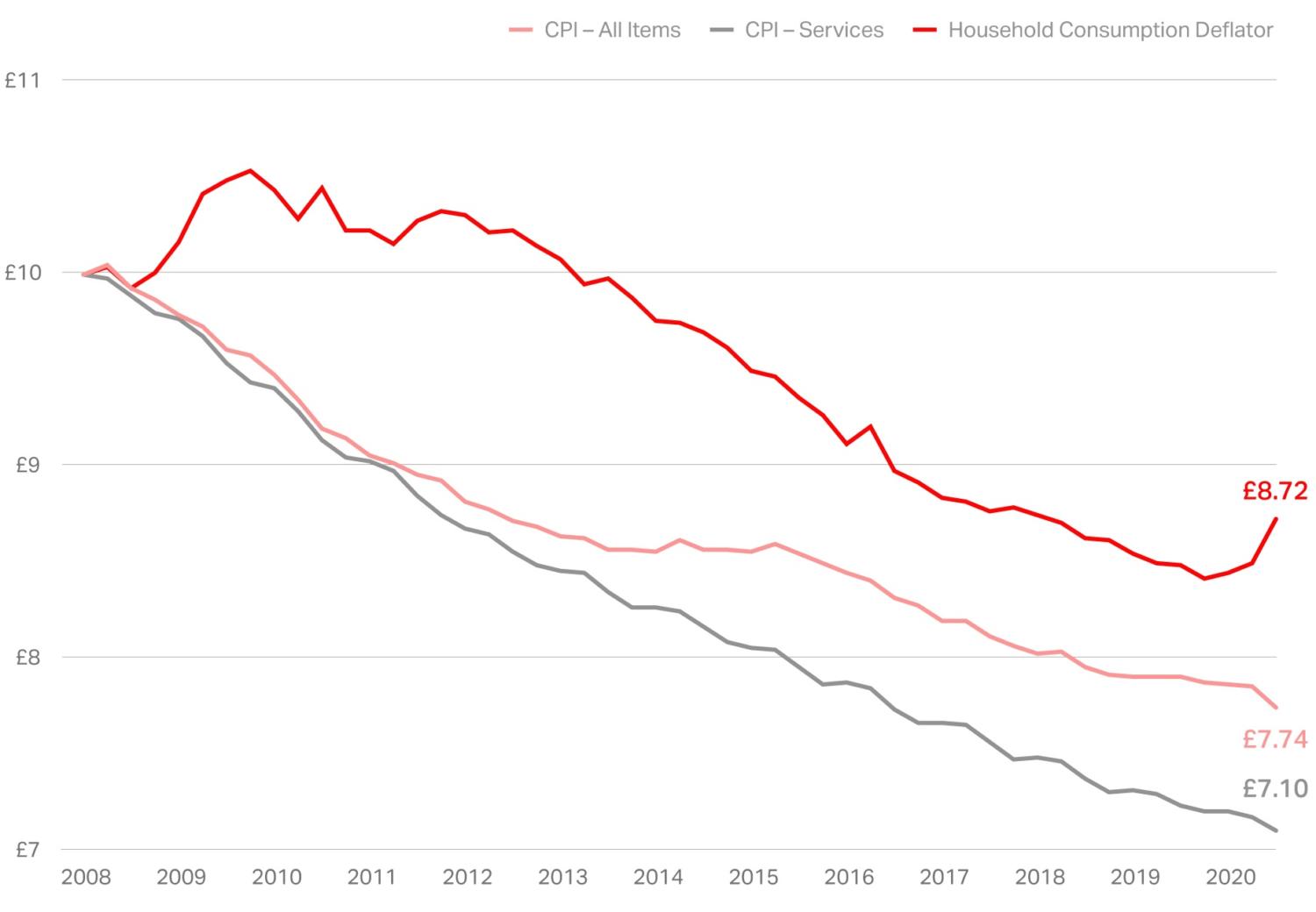

The UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) offers three metrics that are pertinent to the cost of music streaming. The CPI captures everything except housing costs such as mortgages, whereas the CPI Services Index excludes all goods, so no shopping nor petrol. Finally, our preferred metric of household consumption excludes savings and capital expenditure but does capture banking fees and even gambling!

Using any of these three metrics that British wonks use to calculate inflation shows a stark deflationary impact on Spotify’s persistent price since its British launch. Depending on which costs the calculations discard, the value of the sacred 9.99 has fallen by almost 13% using the household deflator, 22% using the headline CPI measure, and 29% to just £7.10 when the more aggressive CPI Services metric is applied.

Figure 1 Deflating the Spotify £9.99 price point

Whether this is good or bad news depends on your perspective. On the one hand, the falling price in real terms has eroded the incomes of artists and songwriters. However, it has also galvanised significant growth, as total consumer spending on music subscriptions rose more than twelvefold between 2013 and 2021,6 to £1.2bn—a success story that has been reflected around the world. Few industries can claim such success. Price may explain it.

We are family

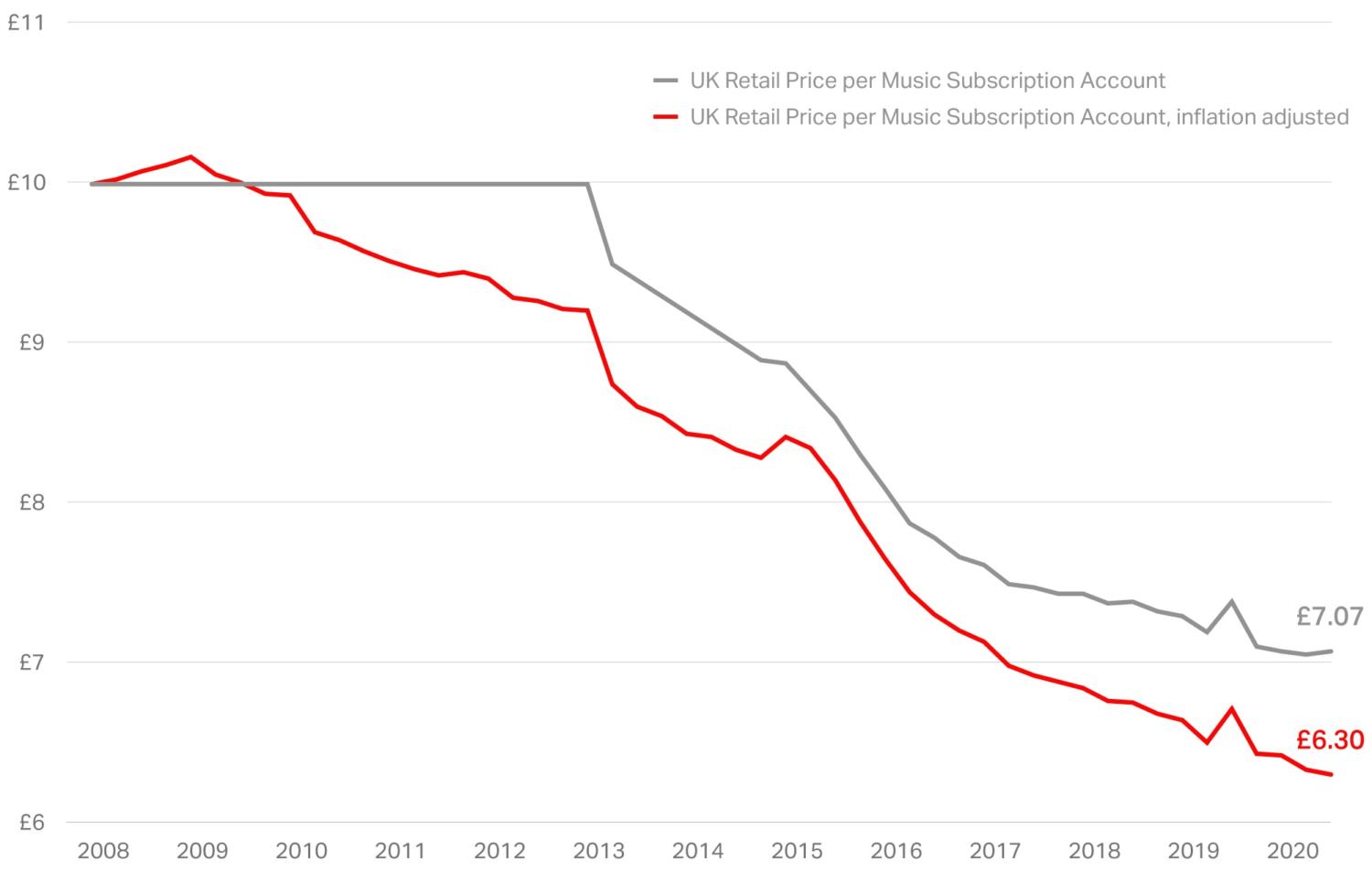

The plot thickens when factoring in Spotify’s family plan, which it launched in the UK in 2014 with little initial uptake.7 However, when Apple Music launched on iPhones in the second half of 2015, with a family plan offered upfront, the proposition of £14.99 for six accounts went mainstream. Assuming there to be 2.3 people per family plan, the cost works out at approximately £6.50 per account, and the student plan launched in 2014 reduced that price further still,8 to £4.99—all before adjusting for inflation.

Now the calculations get complicated. Accounting for these varying price points across the three major services of Apple Music, Amazon Music Unlimited and Spotify, with a blended and weighted calculation, deflates the 9.99 shibboleth to just £6.30 after adjusting for inflation—as opposed to the ‘standalone’ £8.72 in the prior chart.

That’s worth thinking (and drinking) about.

Figure 2 Blended and weighted monthly price of music per account holder

Let’s take a time-out as this gets very hypothetical—after all $9.99 today is worth, well, $9.99 today! What the red line tells us is that the average ‘weighted-subscriber’ across all three major services and across all three pricing plans would have seen the ‘blended cost’ of their subscription fall by over a third (35%), from £9.99 to just £6.30.

There’s a message in a bottle

Let’s digress.

Economists love stripping inflation out of data like a kid playing with a new toy. Clickbait headlines of artists suffering pay cuts miss the point; the business is growing and this is only loosely linked to the hotly debated ‘per stream’ metric—after all, pay more for a streaming service and (subsequently) stream even more music, and you drive the per-stream cost down.

To make a constructive contribution to the conversation about price, we need to ‘uncork’ a comparator, so let’s pour our first glass of ‘Malbeconomics’.

Malbec (‘bad beak’) originated from France, but Argentines quickly noted that Malbec (and lesser-known Torrontés) grapes thrived in their climate and put a lot of effort into their promotion. Torrontés never took off, whereas Malbec’s heavy dark colour and rustic rugged appeal made it a mainstay of menus. Connoisseurs noted that, unlike comparable wines, it didn’t leave a soft silky lingering flavour in the mouth thanks to blackcurrant cassis and firm but integrated tannins. That was the taste of success—Malbec now ranks in the top ten most popular wines in the world.9

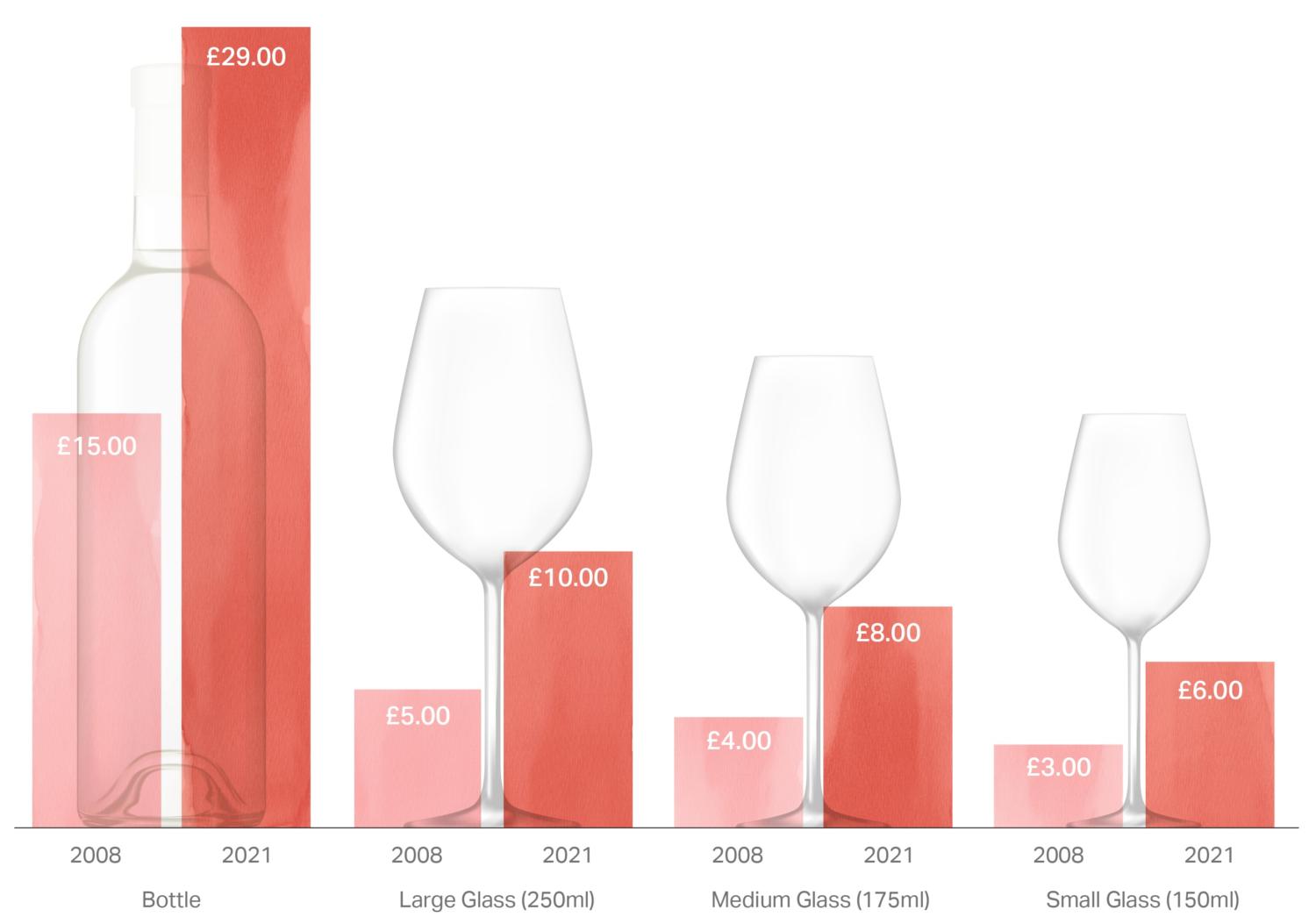

Malbec’s success has been captured in the rising prices that consumers are willing to pay. Kevin O’Rourke, a wine industry expert and founder of wineman.co.uk, found that across all sizes, from a small glass to a bottle, the price you’d pay in today’s restaurant for an ‘entry-level’ Malbec Michel Torino Colección Estate has doubled since 2009.10

Figure 3 Malbec pricing in British restaurants, 2009 and 2021

Cheers. Why is music offering more for the same, whereas wine offers the same for more?

To the reader, the link between rock and roll and alcohol may not be immediately apparent.

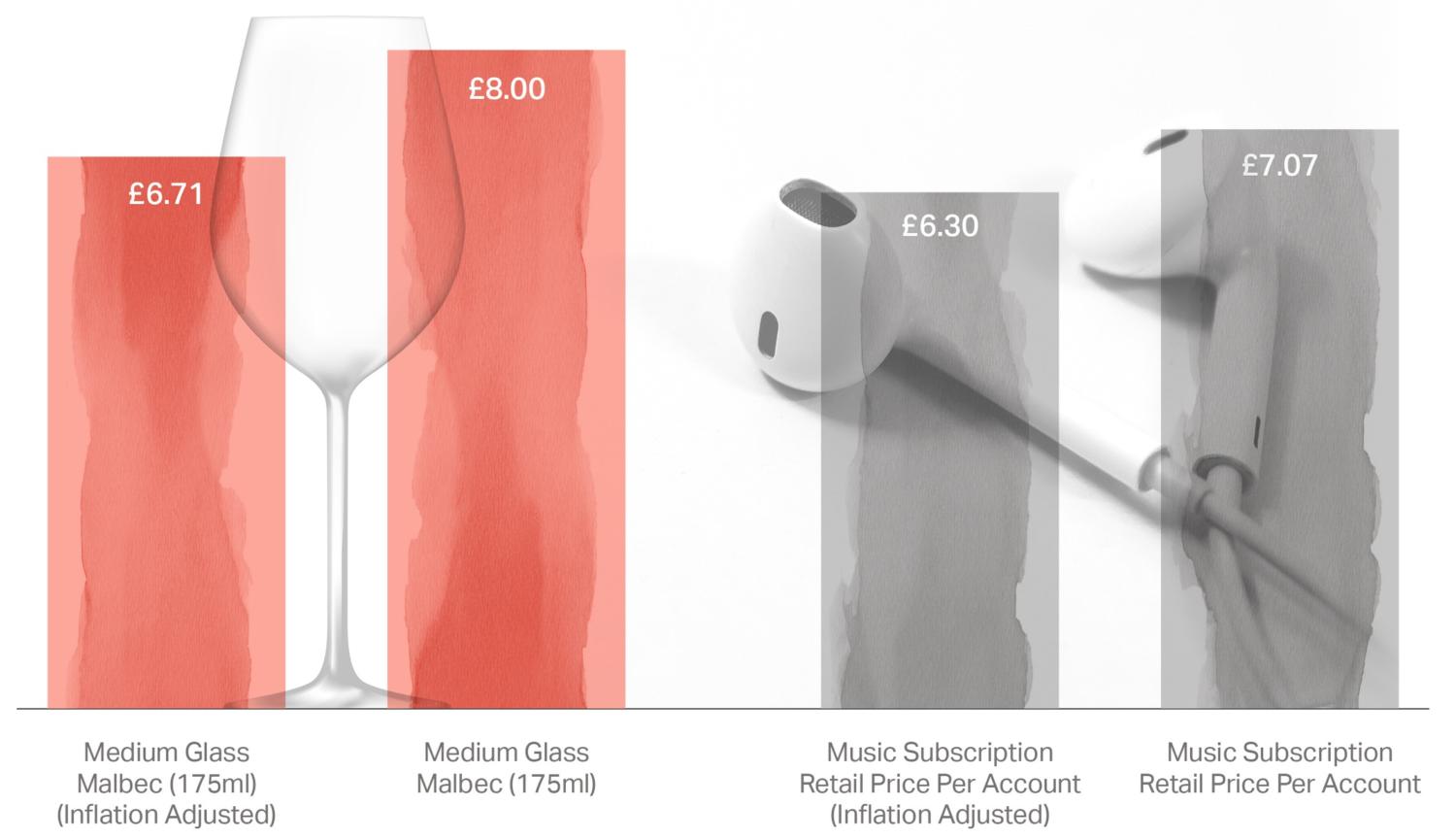

As the chart below shows, a medium glass (175ml) of Malbec now costs more than the blended price of accessing 75m songs on a music streaming service, in both nominal and real terms. If a consumer were to have done only two things in their life since the start of 2009—drinking Malbec and streaming music (not entirely implausible)—today it would ‘feel’ like the latter is cheaper than the former.

Figure 4 Medium glass of Malbec and all the world’s music, adjusted for inflation

Statisticians actually spend a lot of time thinking about exactly this sort of stuff: not wine nor music, per se, but how to factor in service improvements when price remains constant. Using a technique called ‘hedonic pricing’11—not to be confused with the price of living wild in the disco era(!)—‘stattos’ like to adjust for (say) the price of computers: the price remains unchanged, but you got a better chip and more RAM, so they need to factor this into the deflator. My book Tarzan Economics explores ‘Bezos’s Law’, which states that ‘a unit of [cloud] computing power price is reduced by 50 per cent approximately every three years’—requiring a more aggressive deflator as firms are getting more for it.

Today, on the 20th anniversary of the 9.99 price point, streaming’s service improvements have skyrocketed, despite its price remaining unchanged. Song volumes have climbed from just 15,000 tracks on Rhapsody’s 2001 offering to over 75m today (growing at a rate of 75,000 a day). Smartphone streaming apps make these massive libraries imminently accessible, and are constantly being improved. Single accounts have given way to flexible plans with collaborative listening options. And, since the 2015 breakthrough of algorithmic playlists such as Discover Weekly, services can even choose the music for you. Yet the price for music remains not just the same, but cheaper when adjusted for all the participants in the family plan, student pricing and inflation.

Meanwhile, a 175ml glass of Malbec comes from the same grape, packs the same alcohol content and is served at the same volume, yet its face value price has doubled. Indeed it’s true to say that it hasn’t changed one millilitre! Wine is offering the same for more, whereas music is offering far more, for far less.

How long can the song remain the same? The tug of war over label profits and artist payouts needs to grapple with the historic decision 20 years ago to mirror the cost of music to a Blockbuster rental card. The thorny conversation for the artists, executives, politicians and policymakers to thrash out, ideally over a round or two of Malbec, is why this continues to be the case in the UK, USA and Eurozone alike, and when (not if) this should change.

Cheers!

Will Page

I would like to thank Luke Croydon, Andrew Walton, Katherine Kent,Chris Payne and Philip Gooding (Office for National Statistics); Kevin O’Rourke (www.wineman.co.uk); Nick Lightle for his ‘priceless’ modelling skills; Ralph Simon (Mobilium); Luke Butler (Entertainment Retailers Association); Dr Hayleigh Boscher (Brunel University); and Stuart Dredge (Music Ally). Special thanks go to Jez Bell, Chief Licensing Officer at PPL, who first alerted me to the pricing conundrum way back in the fourth quarter of 2008. Hat tips go to wordsmith Sam Blake for copy-editing and Alice Clarke for design.

1 Economists will be quick to point out that the USA gets music cheap, but they often fail to acknowledge that they do not have VAT eating into the licence base, such that consumers are no worse off.

2 See Coscelli, A. (2021), ‘Economics of music streaming’, letter to Julia Lopez MP and George Freeman MP, 20 September and Coscelli, A. (2021), ‘Music streaming’, letter to George Freeman MP, Julia Lopez MP and Julian Knight MP, 19 October.

3 See also House of Commons (2021), ‘Copyright (rights and remuneration of musicians, etc.) bill: Explanatory notes’, June.

4 Wilson, J. (2009), ‘Spotify Opens To U.K. Public’, billboard, 2 November.

5 Sorrel, C. (2011), ‘Spotify Launches in the U.S at Last’, Wired, 14 July.

6 Entertainment Retailers Association (2021), ‘Lockdown streaming drives entertainment sales to £9bn – and fastest growth rate since records began’.

7 Dredge, S. (2014), ‘Spotify launching family plan with cheaper subscriptions for families’, The Guardian, 20 October.

8 Robertson, A. (2014), ‘Spotify offers Premium streaming to US students for $4.99 a month’, The Verge, 25 March.

9 Robillard, H. (2021), ‘10 Best Red Wine Brands 2021 (Prices, Tasting Notes)’, Vinovest.

10 Vivino (2021), ‘Michel Torino Colección Malbec’.

11 See Office for National Statistics (2021), ‘Consumer Prices Indices Technical Manual, 2019’.

Contact

David Jevons

PartnerGuest author

Will Page

Former Chief Economist at Spotify

Related

Related

Time to get real about hydrogen (and the regulatory tools to do so)

It’s ‘time for a reality check’ on the realistic prospects of progress towards the EU’s ambitious hydrogen goals, according to the European Court of Auditors’ (ECA) evaluation of the EU’s renewable hydrogen strategy.1 The same message is echoed in some recent assessments within member states, for example by… Read More

Financing the green transition: can private capital bridge the gap?

The green transition isn’t just about switching from fossil fuels to renewable or zero-carbon sources—it also requires smarter, more efficient use of energy. By harnessing technology, improving energy efficiency, and generating power closer to where it’s consumed, we can cut both costs and carbon emissions. In this episode of Top… Read More