From sports bras to cigarettes: economic analysis of anticompetitive agreements

Discussions and agreements between firms that operate at different levels of the supply chain, such as retailers and their suppliers, are an important part of business life. When entering into vertical agreements, a manufacturer’s aim is often to encourage its retailers to sustain or increase sales of its products. Vertical agreements can also be used to promote a high quality of service or support the positioning of the manufacturer’s brand by the retailer.

From an economics perspective, vertical agreements are much less likely to have anticompetitive effects than horizontal agreements between firms, because the activities of parties at different levels in the supply chain are complementary, and higher prices to consumers would lead to both firms facing a reduction in demand. However, in some cases vertical agreements, especially those involving retail prices, can potentially infringe competition law and cause harm to consumers.

The UK Office of Fair Trading’s (OFT’s) investigations into toys and replica football shirts are well-known cases in which anticompetitive vertical agreements were uncovered. In the first case, toy and board game manufacturer, Hasbro, and ten retailers were found to have entered into retail price maintenance (RPM) agreements, which restricted the retailers’ ability to sell toys at prices other than Hasbro’s wholesale list price. Hasbro was fined £5m, although the retailers did not receive a fine due to their weak bargaining position against Hasbro.1 In the second case, also involving RPM, Umbro and the sportswear retailers JJB Sports, Manchester United and Allsports Limited were fined for agreements that led them to fix the prices of replica kits of the Celtic, Chelsea, Manchester United and England football teams.2

More recently, the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) investigated suspected RPM in the supply of sports bras in the UK.3 It was alleged that a sports bras manufacturer and three department stores had entered into agreements to set a fixed or minimum resale price on certain branded sports bras.4 Following an in-depth investigation, which included a formal Statement of Objections and oral hearings with the firms involved, the CMA concluded that there were no grounds for action, and dropped the case.

A related case involving vertical agreements was the OFT’s investigation into the retail supply of tobacco.5 The case involved agreements that imposed restrictions on the retail pricing of comparable brands. For example, similar brands from two manufacturers were ‘paired’ and, while retailers were free to set the absolute level of prices for the pair, the relative pricing of the two brands was restricted. The OFT found that these restrictions were anticompetitive by their very nature, although its Decision did not assess or conclude on the actual effects on prices. A number of firms subsequently appealed the Decision on the grounds that the agreements were not anticompetitive by object, as they did not cause consumer harm. The Competition Appeal Tribunal quashed the infringement Decision as a result of the flaws pointed out in the OFT’s evidence.6

The box below provides a background to RPM.

Room for economics in object cases?

In general, anticompetitive agreements can infringe European competition law by object or effect. The relevant European Commission guidelines describe agreements that restrict competition by object as ‘those that by their very nature have the potential of restricting competition’.7 In order for an agreement or practice to constitute an object restriction under Article 101(1), it is generally necessary to take into account both the economic and legal context in order to assess whether the agreement is capable of restricting competition; however, there is no need for enforcers to demonstrate actual harmful effects in the relevant market.8 Examples include price-fixing, market-sharing and RPM. Agreements that are not classified as restrictions by object must be assessed on the basis of their effects on competition. The question of defining what constitutes a restriction of competition by object arose in the Cartes Bancaires case, as discussed in the box below.

While economic evidence is often relied on in effects-based cases to measure the actual impact on competition, it can also play an important role in object cases. For example, modelling of economic incentives can be used to measure the potential effects of any alleged behaviour on prices charged, which can be used to assess whether the allegations are plausible or whether an alternative explanation is more likely. In the tobacco case, for example, economic modelling of the market and the incentives of retailers showed that the impact on prices depended on the nature of the agreements, and that certain variants—one of which was corroborated by factual evidence in the case—actually led to lower rather than higher prices.

Quantitative analysis can also be useful for determining whether a particular case should constitute an administrative priority, and may be relevant in determining the level of fines in cases where an infringement is found.

In the sports bras RPM case, economic evidence was used to answer the following questions:

- is the RPM narrative plausible when seen in the context of the retailers’ commercial behaviour during the period in question (e.g. in terms of price-setting, promotions and discounting)?

- what was the overall impact on prices—if any?

Using data to test the anticompetitive narrative against commercial reality

To support an anticompetitive narrative, competition authorities can make use of communications between firms, perhaps relating to a specific date, store and/or product line. However, such communications can be interpreted in different ways and may not actually lead to a change in a firm’s commercial behaviour. Economic analysis of actual prices, discounts and volumes can be used to test whether the competition authorities’ interpretation of the facts is correct, and also to ascertain whether communications between firms translated into changes in competitive behaviour.

The existence of transaction-level data, which is retained by most large retailers, means that detailed empirical analysis is feasible in many cases. For example, if the analysis reveals that, rather than raising prices and/or reducing discounts during the alleged infringement period, the firms in question continued to offer significant discounts and to price independently, this may suggest a different and perhaps more benign narrative to the one put forward by the competition authority.

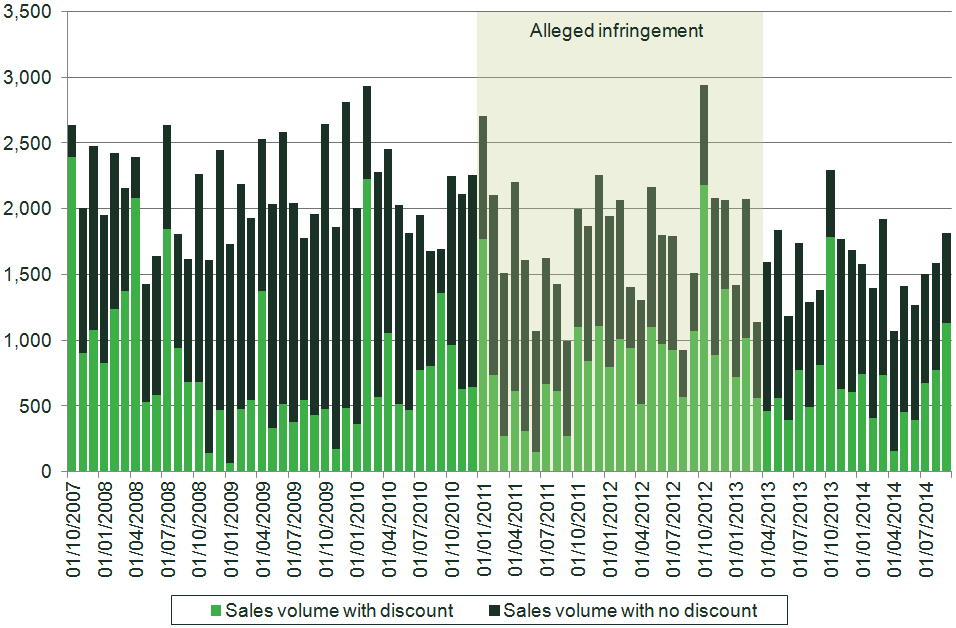

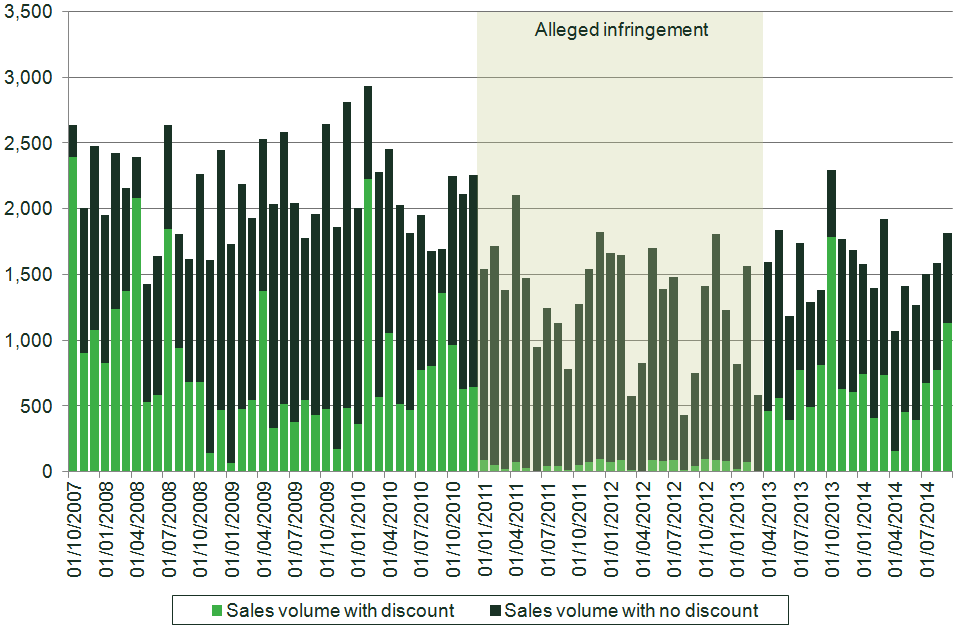

Figure 1 presents a stylised example of a retailer’s discounting behaviour that is inconsistent with an RPM narrative, whereas Figure 2 presents a situation that may be more consistent with RPM. Each figure shows the monthly number of sales at the list price, and the number of sales at a discount. It can be seen in Figure 1 that the firm regularly discounts during the alleged infringement period, whereas in Figure 2 the level of discounting is far less pronounced during this period.

Figure 1 Stylised example of transaction data that is potentially inconsistent with an RPM narrative

Source: Oxera.

Figure 2 Stylised example of transaction data that may be consistent with an RPM narrative

Source: Oxera.

Estimating the counterfactual

Economic analysis can also be used to test the overall impact of the alleged anticompetitive behaviour on prices, sales volumes or margins. In the case of prices, this involves comparing what customers actually paid during the alleged infringement period with the prices that they would have paid without the alleged infringement—i.e. in the counterfactual scenario.

The counterfactual price can be estimated using a number of statistical techniques. The ideal approach will vary depending on the context of the case and the available data, but it might include the following.

- Time series approach—an analysis of prices over time, comparing the infringement and non-infringement periods for the products included in the alleged anticompetitive agreements.

- Cross-section approach—a price comparison between products included in the alleged anticompetitive agreements and suitable comparator products that would be unaffected by any infringement.

- Geographic cross-section approach—a comparison between the prices of the products included in the alleged anticompetitive agreements, and the same products sold in a different geographic market and unaffected by any infringement.

The above are sometimes referred to as ‘single-difference’ methods. In some contexts, they may have technical limitations. For example, when comparing prices over time, if relevant cost shocks unrelated to the alleged infringement are not controlled for appropriately, the results of the analysis may be misleading.

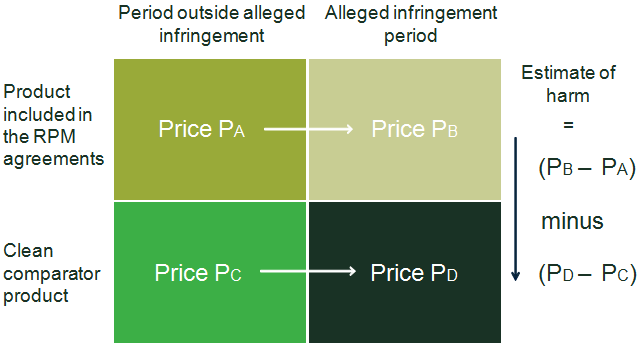

Another method is difference-in-differences analysis. This combines the time series and cross-section analyses. The impact of the infringement is measured by comparing prices of alleged infringement products with those of non-infringement products, as with a normal cross-section analysis. However, rather than carrying out the comparison at a single point in time, the change in the price difference between the two groups of products is analysed over time. This ‘two-dimensional’ technique avoids some of the potential pitfalls of single-difference methods. It is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Stylised form of difference-in-diferences analysis in prices

Difference-in-differences analyses require an appropriate comparator product or geography. Large retailers often sell a wide range of product lines, some of which have similar characteristics. For example, department stores sell both sports bras and non-sports bras. To some extent these two product groups have similar material, labour and distribution costs but, crucially, they are different in terms of functionality. A further benefit of using non-sports bras as a comparator product, as opposed to an alternative brand of sports bra, is that it avoids analytical concerns related to the ‘umbrella effect’.9

Conclusion

Object cases such as RPM have traditionally been approached from a purely legal perspective. However, recent examples such as those discussed in this article clearly highlight the value of using economic evidence as well.

The types of economic analysis that are relevant will depend on each case, but may include theoretical modelling of incentives—as in the tobacco case—or detailed empirical analysis of pricing and discounting behaviour—as in the sports bras case. Either way, a clear understanding of the economic and commercial reality helps to ensure that legal arguments and evidence have a sound and coherent basis.

1 See Office of Fair Trading (2002), ‘Hasbro UK Ltd and distributers: Agreements between Hasbro UK Ltd and distributers fixing the price of Hasbro toys and games’, CA98/18/2002, 6 December.

2 See Office of Fair Trading (2003), ‘Football kit price-fixing’, CA98/06/2003, 1 August; and Competition Appeal Tribunal (2005), ‘Cases 1019/1/1/03 Umbro Holdings Limited v Office of Fair Trading; 1022/1/1/03 JJB Sports PLC v Office of Fair Trading; 1020/1/1/03 Manchester United PLC v Office of Fair Trading; 1021/1/1/03 Allsports Limited v Office of Fair Trading’, [2005] CAT 22, 19 May.

3 Oxera advised a major retailer in this investigation.

4 See Office of Fair Trading (2013), ‘OFT issues Statement of Objections to sports bra supplier and three UK department stores’, press release 64/13, 20 September; and Competition and Markets Authority (2014), ‘Sports bras RPM investigation’, 18 June.

5 See Office of Fair Trading (2010), ‘OFT Imposes £225m Fine against Certain Tobacco Manufacturers and Retailers over Retail Pricing Practices’, press release, 16 April. Oxera advised the Co-operative Group during the OFT investigation and in its appeal of the OFT’s infringement Decision. See Oxera (2012), ‘No smoke without fire? The Tobacco appeals’, Agenda, February.

6 See Competition Appeal Tribunal (2010), ‘(1) Imperial Tobacco Group plc (2) Imperial Tobacco Limited v Office of Fair Trading’, case number 1160/1/1/10.

7 See European Commission (2004), ‘Guidelines on the application of Article 81(3) of the Treaty’, Official Journal of the European Union.

8 See Ortega González, A. (2012), ‘Object analysis in information exchange among competitors’, Global Antitrust Review, 2012, pp. 9 and 44.

9 The umbrella effect refers to a situation in which prices of products not directly included in anticompetitive behaviour are nevertheless raised as a result of the behaviour in question. This is because an increase in prices of the products directly involved in the anticompetitive behaviour reduces the competitive pressure on substitute products, allowing prices for these to be increased as well.

Download

Related

Ofgem’s RIIO-3 Sector Specific Methodology Decision

On 18 July 2024, Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Decision (SSMD) for the forthcoming RIIO-3 price control period for electricity transmission (ET), gas transmission (GT) and gas distribution (GD) networks.1 This follows Ofgem’s consultation on the matter in December 2023.2 RIIO-3 will last for… Read More

The future funding of the England & Wales water sector: Ofwat’s draft determinations

On Thursday 11 July, Ofwat (the England and Wales water regulator) published its much anticipated Draft Determinations (DDs). As part of the PR24 price review, this sets out its provisional assessment of allowed revenues and performance targets for AMP8 (2025–30)—and will be of great interest to water companies, investors,… Read More