Danger mouse: the opportunities and risks of digital distribution

Digital channels create new commercial opportunities and conduct risks (as well as commercial risks) for providers of financial services. There are important questions about the extent of provider responsibility and the nature of liability in a digital environment. But what is different about conduct risk in this context? And how should digital conduct risks be managed? In our experience, providers can manage these risks effectively using a new toolkit of data science and behavioural economics.

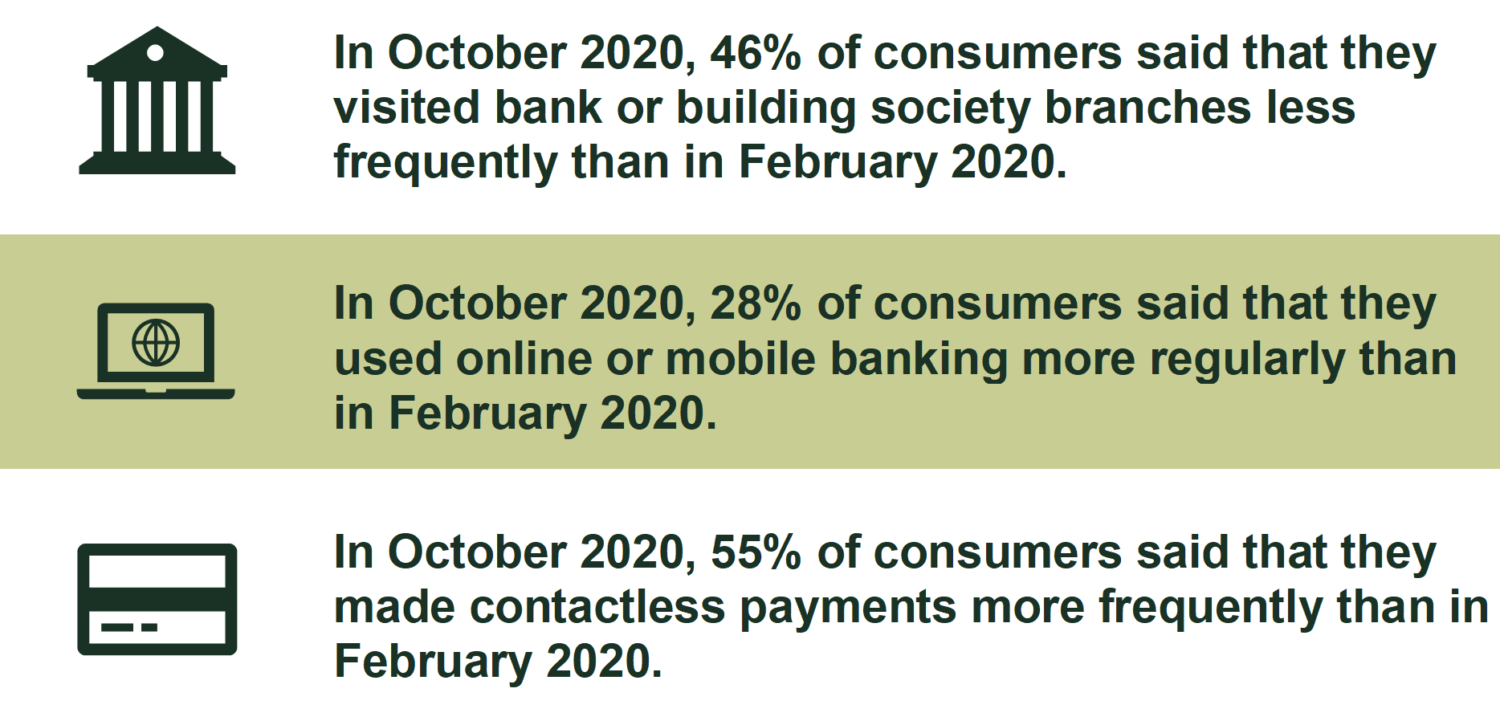

The transition towards digital across the economy is increasingly influencing retail banking, with greater use of digital channels (online, app) and the growth of fintech. Digital channels are important at many stages of the consumer journey and the whole product lifecycle, including the point of sale and ongoing product usage. Moreover, as shown in Figure 1 below, COVID-19 has further accelerated the trend towards digital channels.

Figure 1 The impact of COVID-19 on digital access to retail banking services

Digital practice is evolving rapidly, and the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) expects providers of financial services to remain at (or near) the forefront of good practice.1 The FCA’s expectations cover more than just the point of sale. Providers may be required to assess the digital consumer journey and product lifecycle at each consumer touchpoint, with a detailed understanding of typical customer behaviour and biases. The FCA’s expectations also reflect consumer expectations over digital channels, which are formed through consumer experiences of using digital in financial services and other sectors.

What’s different about digital? A behavioural economics perspective

First, digital channels lack the traditional one-to-one or face-to-face interaction between consumers and providers. This means that providers cannot address conduct risk through in-branch staff interpreting visual or verbal clues about consumers’ level of understanding or strength of intention. For example, in-branch staff may be able to gauge when a consumer does not fully understand the obligations associated with a mortgage, and can adjust the sales process accordingly. In some circumstances, staff may be able to exercise their judgement over whether a consumer is vulnerable.

Consumers often have difficulties understanding retail financial products. For example, research has shown that consumers can struggle to correctly compute compound percentages.2 In mediated channels, any lack of understanding can be addressed immediately by staff. However, in a digital environment, consumers may not have such easy access to assistance, and may take decisions based on miscomprehension.

This is not to say that traditional face-to-face channels are without their challenges. For example, while sales advisers are trained, given appropriate scripts, and monitored, the human element will naturally result in variation in how they speak and behave.

Second, the provision of digital services gives providers access to new, more detailed real-time data on consumers. Consumers may be unaware of how much big data is collected or used by their providers, and may have certain expectations about how their data is used. For example, consumers trust providers to keep their data secure (indeed, one international survey in 2020 found that consumers were more likely to trust banks and other financial services providers with their personal data than other types of organisation).3

Consumers may also expect providers to interpret their data and suggest only products that are suitable for them. For example, a consumer may expect their provider to send them sales information via digital channels about products that are affordable for them (using data about their financial situation). As stated by the FCA, ‘consumers expect firms to take into account their preferences when engaging with them’.4 In addition, a consumer may expect their provider to flag if they are making a payment to an account number that is known to be associated with suspicious activity.

Third, consumer behaviour is susceptible to influence via digital channels in different ways to mediated channels. The choice architecture of digital channels—the way in which choices and options are framed—has been shown to be highly influential in affecting decisions (for example, in terms of ‘dark patterns’ or ‘sludges’).5

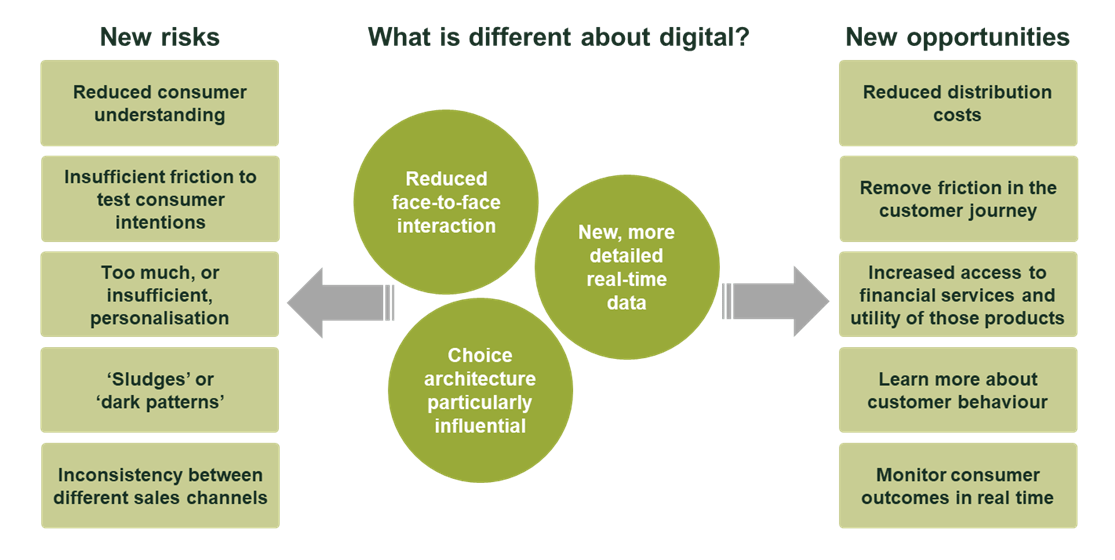

These differences result in new opportunities and new challenges from a conduct risk perspective (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 New opportunities and risks

New opportunities?

Digital channels present providers with a number of commercial opportunities, as follows.

- Reduced distribution costs, unlocking greater profitability and cheaper products for consumers. Estimates of cost efficiencies offered by digital channels (compared with the alternatives) vary according to the level of efficiency of the branch network or call centre operations, and the level of efficiency of the new digital channel. These will depend on economies of scale (i.e. on how many customers use the digital channel). One study estimated that the online cost per transaction could be up to 95% lower than the in-branch cost per transaction.6 The methodology behind this estimate is unclear, but the cost savings from digital channels are likely to be significant. The extent of pass-on to consumers will depend on the nature of the costs (e.g. variable, fixed), and the market structure (e.g. perfect competition, oligopoly or monopoly).

- Increased access to financial services and utility of the products, through expanding the reach of products (e.g. reaching new customers, and reaching existing customers with new products). One such example is that of robo-advice increasing access to wealth management advice. One study found that, assuming that offering robo-advice increases upfront fixed costs (the cost of programming the robo-adviser), but reduces per-customer costs (i.e. there are greater returns to scale than in traditional advice), robo-advice increases access to advice for lower-income consumers.7 Further, digital access increases the consumer value provided by some products—for instance, when someone monitors their current account balance via an app rather than through monthly statements in the post.

- Information about customer behaviour. The data generated by digital channels gives providers new insights into the preferences and choices of consumers, and what drives these choices. In this respect, ‘know your customer’ has never been easier.

There are also opportunities for the removal of friction in the customer journey, increasing providers’ ability to make sales; and the monitoring of consumer outcomes in real time, allowing providers to intervene immediately if certain patterns in behaviour emerge (e.g. suspicious transactions).

New risks?

However, there are also risks with digital channels.

- Reduced consumer understanding. A frictionless consumer journey may not adequately prompt consumers to take time to understand the product, and providers may be unaware of the level of consumer understanding. For example, while consumers have to click to indicate that they have read a set of terms and conditions, they may spend very little time on the page. Indeed, a particular screen may never result in a good enough understanding of some complex products. This means that it may not be appropriate for some products to be sold via digital channels.

- Insufficient friction to test consumer intentions. A frictionless consumer journey may not adequately prompt consumers to consider their purchase decision—consumers need to consider their rights and obligations under any product.8 For example, the FCA has highlighted these risks regarding younger retail investors who are using digital channels to make high-risk investments (e.g. in cryptocurrencies or foreign exchange).9

- Too much, or insufficient, personalisation. If consumers’ expectations over the degree of personalisation are incorrect, there is a potential for conduct risks. For example: (i) consumers who overestimate the degree of personalisation may interpret sales suggestions as personally recommended for them, and therefore suitable for their needs and circumstances (when they may not be); and (ii) consumers who underestimate the degree of personalisation may lose trust in their provider when they realise that their personal data is being used to target communications or tailor product design.

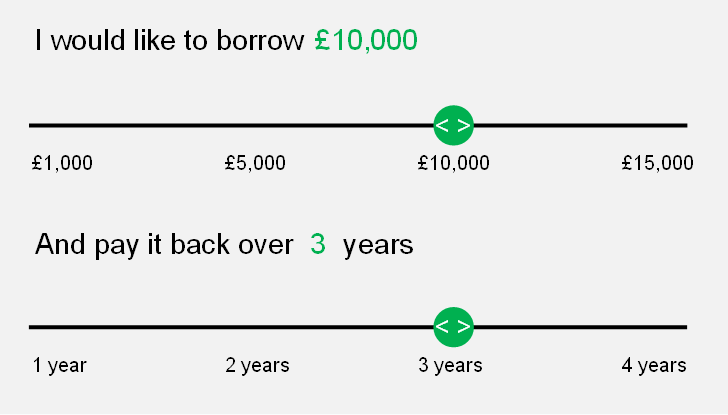

- ‘Sludges’ or ‘dark patterns’. Behavioural economics tells us that the way in which information and choices are presented can have a significant impact on the decisions taken by consumers—there is no such thing as a neutral choice architecture. Small changes in the choice architecture can have a big (intended or unintended) impact on outcomes. A lot of ‘rational’ or ‘irrational’ consumer behaviour can be predicted in advance, as shown by empirical evidence in the behavioural economics literature. Further, since outcomes can be tested, providers would be expected to understand the impact of their choice architecture on behaviour and be able to justify their design of choice architecture. For example, using anchors in the presentation of choices for credit products can influence consumers (see Figure 3 below).10

Figure 3 Use of anchors at the point of sale in consumer credit

- Inconsistency between different sales channels. Providers are required to manage which products are available to which consumers via digital channels. Digital distribution channels may not be appropriate for all products, and each product requires a well-defined target market.11 In practice, customers may start the customer journey on one channel, and complete it on another channel. For example, a customer might start by using online banking, encounter an issue and so use an app chat function, and finally complete the process by telephoning the bank. This raises the possibility that customers do not receive all the required information through one channel or receive inconsistent information, and the provider may struggle to track the journey from end to end.

Other risks include misuse of personal data, financial crime, operational resilience, data security and cybersecurity issues. Providers need to demonstrate how they will protect themselves and consumers from these threats. Lastly, as highlighted by the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) Discussion Paper on open insurance,12 there is a risk of financial exclusion for customers who do not use digital channels.

Mitigating the risks

Providers face a vast array of design options over digital channels. In our experience, providers find it helpful to set out their high-level design principles for these channels. These principles would cover what the provider does (and does not) design its digital channels to achieve, and how the provider uses (and does not use) consumer data.

Practical design choices would flow from the digital design principles. These could include:

- empowering consumers by giving them choice over the level of control. Consumers may wish to opt into (or out of) control over how they use products. Some consumers may prefer assistance, while others may find it overbearing. This might be analogous to choices over parental control for Internet use, which can be changed by consumers at a later date;

- monitoring patterns and spotting anomalies. Greater data about consumer behaviour may enable providers to identify behavioural anomalies (compared with a consumer’s fitted profile). This may allow providers to step in and check that consumers are acting in their own best interests, or have not been victims of fraud. For example, a provider could check that a consumer has not mistyped when making a payment for an unusually large amount of money via an app;

- differentiating between digital information and sales. Some providers combine information about products and sales information on their digital channels. Ensuring separation between information and sales could mitigate the risk of consumers not understanding that they are purchasing a new product, or being pushed into purchasing new products.

Setting out clear design principles would also help to address governance risks through accompanying clear frameworks of governance and accountability. It would then be clear who holds the duty to consider and challenge any potential disconnects that could exist between the design principles and practical design choices, risk appetite, or management capability.

Further, existing practices may need to be strengthened:

- operating a robust testing procedure and audit trail, such as experimenting with changes to digital channels to understand the impact of the choice architecture on consumer behaviour (e.g. A/B testing). Such testing is part of good-practice digital design;

- auditing and monitoring of digital channels from a behavioural economics perspective to ensure that digital choice architecture does not trigger a conduct risk (e.g. play on behavioural biases). The FCA may conduct similar exercises in the future, and providers may find it useful to have documentation showing that their digital channels strike the appropriate balance between selling products and offering clear and fair choices;

- measurement and monitoring of consumer outcomes on an ongoing basis, so that any variations in outcomes are detected and understood. These include both financial and non-financial outcomes, which may indicate that a product is being used as intended (or otherwise), or whether consumers are reading the terms and conditions (which many consumers do not).13 Appropriate consumer segmentation is important in the monitoring of consumer outcomes, and digital outcomes can be benchmarked against outcomes of consumers using other channels (controlling for the fact that consumers self-select into different channels);

- facilitating digital feedback and monitoring complaints data. It may be appropriate for consumers to be able to register complaints and feedback through the digital channels, and such feedback must be monitored. The use of ‘live chat’ functions is an important way for providers to ensure that consumers can easily reach out if they do not understand something.

Implications going forward?

Digital channels present providers with a number of commercial opportunities, including reduced distribution costs, increased access to financial services and utility of the products, and greater learning about customer behaviour.

While digital channels come with conduct risks for providers—such as reduced consumer understanding and insufficient friction to test consumer intentions—these can be efficiently managed and monitored using behavioural economics and data science. Investing in these two capabilities may be the best step that an organisation can take to balance the management of digital conduct risk with the ability to capitalise on digital commercial opportunities.

1 Financial Conduct Authority (2019), ‘Regulation in a changing world’, speech by Christopher Woolard, Executive Director of Strategy and Competition at the FCA, 21 October; Financial Conduct Authority (2015), ‘Social media and customer communications: the FCA’s supervisory approach to financial promotions in social media’, FG 15/4, March.

2 See Oxera and the Nuffield Centre for Experimental Social Sciences (2017), ‘Annex 5: Identifying metrics to aid consumer choice in the income drawdown market’, prepared for the FCA, March.

3 Genesys (2020), ‘Survey Shows Banks, Healthcare Providers, and Government Remain Most Trusted by Consumers, Despite Lack of Transparency and Data Security Breaches’, PR Newswire, 11 June.

4 Financial Conduct Authority (2016), ‘Smarter Consumer Communications’, Feedback Statement FS16/10, October, para. 2.33.

5 Authority for Consumers and Markets (2019), ‘Protection of the online consumer: boundaries of online persuasion’, Guidelines, Draft consultation document.

6 McKinsey & Company (2017), ‘The Winning Formula for Omnichannel Banking in North America’, Retail Banking Insights 9, January.

7 Philippon, T. (2019), ‘On Fintech and Financial Inclusion’, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working paper 26330.

8 Financial Conduct Authority (2016), ‘Business Plan 2016/17’, p. 19: ‘The growth of mobile and digital channels offered by firms has been supported by the creation and take-up of supportive technology, from mobile payment and digital wallet services, such as Apple Pay, to integrated billing. […] [T]he limited information and the speed of action consumers experience could lead to inappropriate decision making’.

9 Financial Conduct Authority (2021), ‘FCA warns that younger investors are taking on big financial risks’, Press Release, 23 March.

10 See Financial Conduct Authority (2017), ‘From advert to action: behavioural insights into the advertising of financial products’, Occasional Paper 26, April.

11 Financial Conduct Authority (2018), ‘FCA Handbook’, PROD 3.2 Manufacture of products.

12 EIOPA (2021), ‘Open insurance: accessing and sharing insurance-related data’, Discussion Paper. See also, for example, Financial Conduct Authority (2018), ‘FCA Mission: Approach to Consumers’, p. 31: ‘Technological innovation and change is transforming the financial services market for consumers. For example, increasing numbers of consumers can access services through mobile and digital devices which bring convenience and choice but can leave some consumers excluded’. See also Financial Conduct Authority (2018), ‘Business Plan 2018/19’, p. 27: ‘The increased use of big data also has the potential to cause harm. There is a risk that if technology and innovation move too quickly, the more vulnerable in society could be at a disadvantage’.

13 Bakos, Y., Marotta-Wurgler, F. and Trossen, D.R. (2013), ‘Does Anyone Read the Fine Print? Consumer Attention to Standard Form Contracts’, New York University Law and Economics Working Papers, March.

Download

Related

Ofgem’s RIIO-3 Sector Specific Methodology Decision

On 18 July 2024, Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Decision (SSMD) for the forthcoming RIIO-3 price control period for electricity transmission (ET), gas transmission (GT) and gas distribution (GD) networks.1 This follows Ofgem’s consultation on the matter in December 2023.2 RIIO-3 will last for… Read More

The future funding of the England & Wales water sector: Ofwat’s draft determinations

On Thursday 11 July, Ofwat (the England and Wales water regulator) published its much anticipated Draft Determinations (DDs). As part of the PR24 price review, this sets out its provisional assessment of allowed revenues and performance targets for AMP8 (2025–30)—and will be of great interest to water companies, investors,… Read More