Can effective communication empower consumers?

The UK Financial Conduct Authority’s (FCA) smarter consumer communications initiative places product disclosure at the centre of the authority’s efforts to ensure consumer protection and facilitate competition. The FCA recognises that poorly designed regulatory disclosure material that does not present information in a clear and accessible way can hinder consumers’ ability to make informed decisions. But what is good disclosure practice, and how can behavioural insights be used to improve disclosure?

The FCA has called on financial services firms to consider innovative ways of engaging and communicating with consumers in order to help them make decisions about the products and services that they buy.1 The FCA’s outcome-based approach to regulation and supervision places responsibility on firms to ensure that good consumer outcomes are achieved, which in turn means that consumers are able to access and assess relevant information about products and services and then, importantly, act on that information.2 So, while firms (and in particular their marketing departments) are likely to know very well how to get messages across to customers, the FCA approach requires some of the same tools and techniques to be applied to help consumers understand the available products in order to make an informed choice.

Information alone may not be sufficient to empower consumers to make informed choices. Consumers can often be overwhelmed and confused by information that financial services firms are required (by regulation) to disclose.3 Effective and engaging information can be a powerful tool to help put consumers in control of their decisions and hence facilitate competition.

Small things can have a big impact in terms of effective disclosure, and experience from successful (as well as less successful) product disclosure initiatives can help to identify how firms can communicate effectively. This article looks at a number of examples in and outside the financial services sector, drawing on the lessons from behavioural economics research, to provide some insights into what good practice might look like.

Regulatory involvement in product disclosure in different sectors

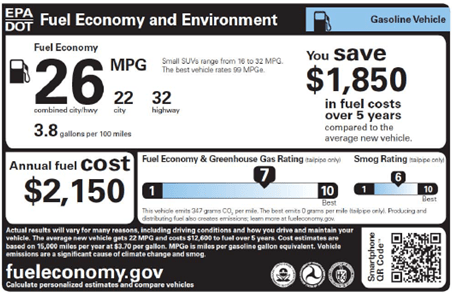

Initiatives aimed at putting consumers back in control of their decision-making through the provision of information is not a concern solely in the financial services sector. In the USA, nutrition information displayed on foodstuffs has been overhauled to make it easier to understand.1 Similarly, a new vehicle labelling system has been introduced in the USA that provides five-year fuel costs and compares fuel savings to an average vehicle (as shown in the figure below).

Environment Protection Agency fuel efficiency label

Timing of information is as important as the content itself. In the EU, mobile providers are now required to send a text message with the relevant charges when the user has crossed national borders. Moreover, the provider must send a text message when data-roaming charges have reached €50 and the consent of the user is needed before more data services are provided.2

Note: 1 USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion (2011), ‘A Brief History of USDA Food Guides’, July. 2 See European Commission

website, http://ec.europa.eu/digital-agenda/roaming, accessed 3 August 2015.

Source: Oxera.

What, how and when to communicate?

Product disclosure is the provision of information before, during or after a transaction that informs the consumer about the features, benefits, risks and costs of a product. The format of disclosure may vary depending on the product design, distribution channel and marketing strategy of the firm. Information can be presented in various ways, and can be communicated verbally, in writing, or via a figure or graphic—perhaps the most vivid example of product disclosure being cigarette package warnings with graphic images of the adverse effects of smoking. The discussion around disclosure considers what, how and when to communicate in order to best inform the consumer.

The provision of more information does not necessarily mean that consumers actually read, process and ultimately incorporate that information into their decision-making process. Many consumers often fail to read disclosure documents fully, due to the high volume and/or the complexity of information. Indeed, recent research has found that 84% of UK adults do not read the full terms and conditions when purchasing financial products.4

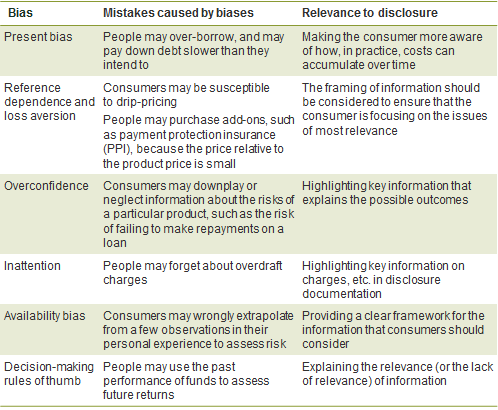

In particular, behavioural biases can affect how consumers assess and access information that is available to them (see Table 1 for a list of potential biases and how they relate to product disclosure). For example:

- consumers often do not have access to product information, either due to inertia and procrastination or because they do not know where to look for the information;

- consumers may not be able to properly assess and understand the information because they may be influenced by how the information is framed; they may find the information complex and challenging; or they may choose to focus on particular pieces of information that are easily accessible but not particularly important.

Thoughtfully designed disclosure can frame the relevant decision in a way that mitigates the effects of behavioural biases by bringing critical information to the forefront of consumers’ attention.

Table 1 The relevance of behavioural biases to product disclosure

As the objective is to encourage good consumer outcomes, testing disclosure is important in order to ensure that information is presented to consumers in a helpful and directed manner. The importance of testing is highlighted by the experience of a US Federal Reserve proposal to require disclosure for mortgage broker commissions, in order to address concerns about conflicts of interest and improve transparency.5 The proposal was not adopted, however, as research showed that consumers would place too much emphasis on the commissions and too little on the interest rate of the mortgage, and end up selecting more expensive mortgages than they would have done in the absence of the commissions information.6 The Federal Reserve’s proposal was well intended, but testing avoided potential unintended consequences and ensured that consumers were responding appropriately to the information provided.

Some examples of effective disclosure

Effective disclosure can help to improve consumer choice, both by providing information on the key aspects of the product in a manner that is both engaging and comprehensible, and by helping consumers to compare across different products.

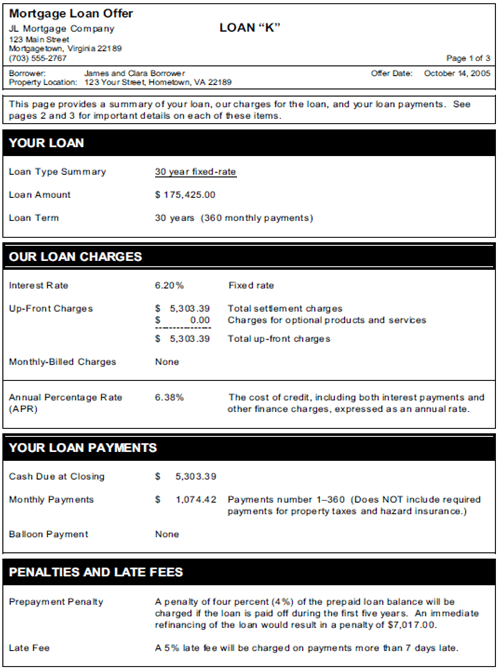

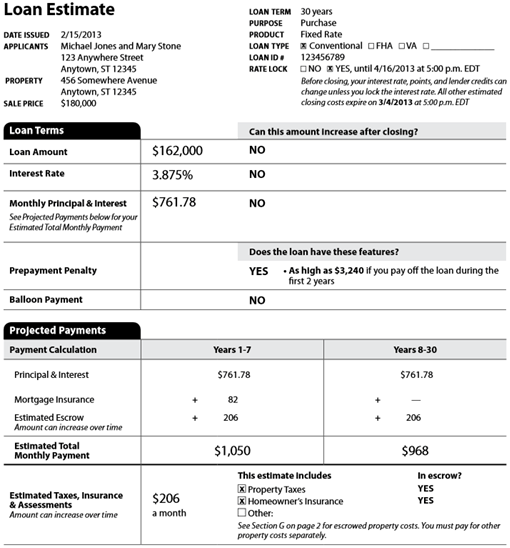

Lengthy disclosure documents may result in information overload, which in turn can cause consumers to either ignore information or fail to discern which information within a disclosure document is important.7 As a result, it may be helpful for a provider to ‘layer’ information, where the consumer receives a summary disclosure of the most important information upfront, with clear signposts to additional information. An example of summary disclosure is shown in Figure 1, which captures all of the key information for a mortgage on one page.

Figure 1 US Federal Trade Commission prototype mortgage disclosure

Disclosure is effective only if it also manages to engage consumers. This can be done via various methods, such as providing eye-catching content—even if this is uninformative—and using reminders to direct attention to the appropriate information at the right time. Existing good practice aims to present information in a way that helps consumers to process and understand the content. Much of this good practice is perhaps unsurprising, but it is still useful to highlight some of the key measures, which suggest that disclosure should:

- place the most important information where consumers are expected to focus their attention—for example, many people disregard the body of a letter and focus on the headlines;8

- use simple language and short messages wherever possible—for example, the UK Behavioural Insights Team has found that letters with simplified language were much more effective at inducing tax compliance than traditional letters drafted by UK tax authorities;9

- present images that summarise the information contained in the text—for instance, the Behavioural Insights Team conducted an experiment whereby drivers who had not paid their car tax were sent a letter along with a photo of their unlicensed car captured by a traffic camera. The addition of the photo increased relicensing rates from 22% to 33%;10

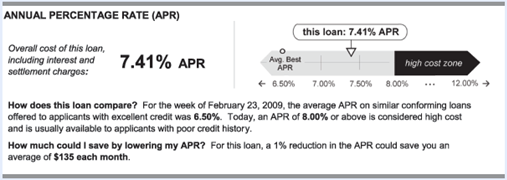

- present ratings or warnings for products that rate poorly compared with their counterparts, in order to highlight the downside of the particular product vis-à-vis its competitors. Examples of scales that are used for comparing products include vehicle fuel economy stickers (as in the figure in the box above) and annual percentage rate graphics for home-secured credit (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Federal Reserve Board’s home-secured credit disclosure graphic

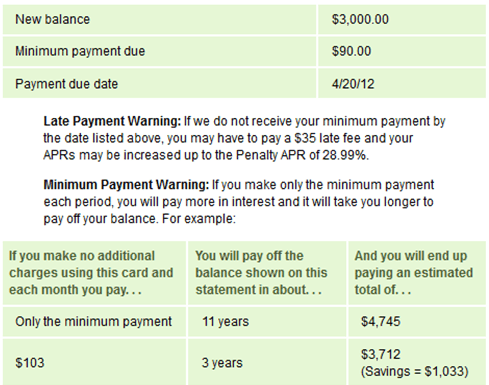

Providing estimates based on ‘typical’ usage can be useful for informing consumers about the actual costs of a product. Giving monetary estimates of typical performance for ‘good’ outcomes and ‘bad’ outcomes may also be helpful—the US Credit CARD Act 2009 advocates disclosure that does this, as shown in Figure 3.11

Figure 3 Example of credit card disclosure under the US Credit CARD Act 2009

Aspects specific to financial services products

Financial services products have certain attributes that need to be addressed in effective disclosure. In particular, they involve an element of risk with uncertain costs and returns; they have multiple prices and price points; and they commonly use percentages and compounding, which many consumers have trouble understanding.

Risk is an integral part of many financial services products. Many consumers have difficulty assessing risk and can be easily influenced by how the information is framed and presented. Consumers tend to use information that may seem intuitively useful, although in reality it may be spurious. For example, in assessing funds, consumers tend to place a lot of weight on past performance, even if they are warned that it is unrelated to future returns.12

Research findings indicate that graphic images and categorical labels can potentially help people to assess risk. For instance, a food labelling field experiment13 found that displaying quantitative information in a categorical format (e.g. by stating that something was ‘low-fat’ rather than saying that it contained 5g of fat per serving) has a significant and positive impact on consumer behaviour. People tend to place more importance on outcomes that are particularly memorable or highly emotional, which can be used to encourage consumers to take note of pertinent information and hence better assess risk.14

With regard to percentages and compounding, several studies have found that showing charges and fees in absolute terms, rather than as percentages, can help consumers to better understand the product features.15 Some regulators require charges to be displayed in both percentages and absolute terms for specific products. As part of its ‘Know Before You Owe’ initiative, the US Consumer Financial Protection Bureau requires that mortgage providers list all costs and payments in dollars and cents (as in Figure 4), in addition to giving the interest rate.16

Figure 4 ‘Know Before You Owe’ sample disclosure

Disclosure of product usage

Regulatory initiatives have, by and large, centred on the disclosure of product features. However, the total cost and benefit of a particular product depend on the product attributes and costs as well as the overall usage of the product. Disclosure has a role in reducing misperceptions, in terms of both the product attributes and the future usage of the product. A more recent regulatory approach called ‘Smart Disclosure’ has been encouraging the disclosure of information on consumers’ own usage patterns.17 Consumers can then upload their usage information into a comparison website, which can tell them the potential cost of their usage from other providers. Product usage information can also be used by the same provider to recommend contracts that may be more suitable. Some initiatives based on this idea have already begun, such as those known as ‘MyData’ or ‘MiData’ in the UK. For example, the aim of the UK government’s midata programme announced in 2011 was to ‘give consumers increasing access to their personal data in a portable, electronic format … Individuals will then be able to use this data to gain insights into their own behaviour, make more informed choices about products and services, and manage their lives more efficiently.’18

Conclusion

Effective communication with consumers can be an important driving force for improving consumer outcomes. This is particularly important in financial services, in which some products can be complex and abstract. A number of characteristics of good disclosure have been identified that have consistently improved consumer engagement and understanding. Implementing these elements in product disclosure is a low-cost and non-intrusive change that can increase market transparency and benefit consumers.

This article is based on Oxera (2014), ‘Review of literature on product disclosure’, prepared for Financial Conduct Authority, 29 October.

1 Financial Conduct Authority (2015), ‘Smarter consumer communications’, DP15/5, 25 June, accessed 3 August 2015.

2 The UK Office of Fair Trading (OFT) set out the ‘access, assess and act’ framework for understanding consumer behaviour in 2010. See Office of Fair Trading (2010), ‘Behavioural economics and competition policy’, presentation by Amelia Fletcher, OFT behavioural economics seminar, 22 April.

3 As shown by research from behavioural economics. See, in particular, Sunstein, C.R. (2013), Simpler: the future of government, Simon and Schuster; and Bar-Gill, O. (2012), Seduction by Contract: Law, Economics, and Psychology in Consumer Markets, Oxford University Press.

4 The Money Advice Service (2014), ‘Misunderstanding financial T&Cs cost UK adults £21 billion last year’, press release, 3 September.

5 Federal Reserve Board (2011), ‘Statement of Sandra F. Braunstein, Director, Division of Consumer and Community Affairs, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, before the Subcommittee on Insurance, Housing, and Community Opportunity, Committee on Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, D.C., July 13, 2011’, accessed 17 August 2015.

6 Lacko, J.M. and Pappalardo, J.K. (2004), ‘The Effect of Mortgage Broker Compensation Disclosures on Consumers and Competition: A Controlled Experiment’, Federal Trade Commission Bureau of Economics Staff Report, February.

7 Ben-Shahar, O. and Schneider, C.E. (2011), ‘The Failure of Mandated Disclosure’, University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 159, pp. 687–90.

8 Cabinet Office Behavioural Insights Team (2012), ‘Applying behavioural insights to reduce fraud, error and debt’, February, p. 10.

9 Cabinet Office Behavioural Insights Team (2012), ‘Applying behavioural insights to reduce fraud, error and debt’, February.

10 Cabinet Office Behavioural Insights Team (2012), ‘Applying behavioural insights to reduce fraud, error and debt’, February.

11 For example, the Act requires that credit card statements show the additional costs in terms of time and interest payments from paying off debt by minimum instalments, versus paying off the debt more quickly. Federal Reserve Board (2010), ‘New Credit Card Rules Effective Feb.22’.

12 Diacon, S. and Hasseldine, J. (2007), ‘Framing effects and risk perception: The effect of prior performance presentation format on investment fund choice’, Journal of Economic Psychology, 28:1, pp. 31–52.

13 Kiesel, K. and Villas-Boas, S.B. (2013), ‘Can information costs affect consumer choice? Nutritional labels in a supermarket experiment’, International Journal of Industrial Organization, 31:2, pp. 153–63.

14 Chuah, S.H. and Devlin, J. (2011), ‘Behavioural economics and financial services marketing: a review’, International Journal of Bank Marketing, 29:6, pp. 456–69.

15 For example, see Hastings, J.S. and Tejeda-Ashton, L. (2008), ‘Financial literacy, information, and demand elasticity: Survey and experimental evidence from Mexico’, NBER Working Paper No. 14538.

16 See Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, ‘Know Before You Owe’, accessed 3 August 2015.

17 For example, steps have been taken towards smart disclosure in the USA: Data.gov, ‘Smart Disclosure Policy Resources’, accessed 17 August 2015.

18 Department for Business, Innovation & Skills (2011), ‘The midata vision of consumer empowerment’, Announcement, 3 November, accessed 18 August 2015.

Download

Related

Ofgem RIIO-3 Draft Determinations

On 1 July 2025, Ofgem published its Draft Determinations (DDs) for the RIIO-3 price control for the GB electricity transmission (ET), gas distribution (GD) and gas transmission (GT) sectors for the period 2026 to 2031.1 The DDs set out the envisaged regulatory framework, including the baseline cost allowances,… Read More

Time to get real about hydrogen (and the regulatory tools to do so)

It’s ‘time for a reality check’ on the realistic prospects of progress towards the EU’s ambitious hydrogen goals, according to the European Court of Auditors’ (ECA) evaluation of the EU’s renewable hydrogen strategy.1 The same message is echoed in some recent assessments within member states, for example by… Read More