Brexit: the implications for UK ports

The UK Prime Minister, Theresa May, has vowed to maintain the frictionless transport of goods between the UK and EU after Brexit—although this language has changed recently to ‘as frictionless as possible’.1 However, Michel Barnier, the EU’s Chief Negotiator, has suggested that it is not possible to leave the Single Market and build a customs union to achieve frictionless trade.2 So how ‘frictionless’ can this trade actually get?

Let’s start with some facts. UK goods trade with the EU amounts to £466bn, split 57:43 between imports and exports.3 Putting some flesh on the bones, this includes everything from food to manufactured goods destined for final assembly (e.g. at the new electric Mini facility in Oxford). This isn’t just about the UK and nearby countries in Continental Europe such as France and Belgium, either. It has been estimated that around two-thirds of Irish exports to the continent move via the UK.4

Since the Single Market was established on 1 January 1993, goods leaving the UK for elsewhere in the EU, and vice versa, have not been subject to customs checks on either side. In contrast, according to the Port of Dover,5 lorry-loads of goods entering Dover from outside the EU (around 3% of the total) are subject to checks that take 45 minutes on average, having been subject to the same checks on entering the EU. Post Brexit, adding four of these checks (at an Irish port, at two English ports, and then at a French one) onto each consignment of Irish goods, say, starts to look unpalatable.

A flourishing supply chain for many manufactured goods has grown up using facilities on either side of the English Channel:

- a fuel injector for a diesel lorry sold in the UK will have crossed the Channel five times before the truck is even driven by the customer;6

- a crankshaft for a BMW Mini will have crossed the Channel three times in a 2,000-mile journey before the car is finished.7

Clearly, the UK elements of this chain are particularly at risk if the cost and uncertainty created by customs checks (which can vary considerably in duration) are deemed to outweigh the benefits of doing business in the UK.

One important barrier to ensuring the delivery of frictionless trade is the small matter of a new government IT system. It was agreed well before the Brexit referendum was announced that the current UK customs clearance system, CHIEF, would be replaced in March 2019. The new system is now due to be delivered just before the UK leaves the EU and, having been planned to deliver 60m clearances per year, it will now need to deliver 300m,8 with no understanding yet of what the customs deal with the EU will look like.

A further reason why it will take time to get the necessary provisions in place for Brexit is due to the UK’s planning system. Despite ‘Operation Stack’ (effectively a contingency queuing/car parking system designed to manage a backlog of traffic trying to cross the Channel) being repeatedly implemented in summer 2015 due to disruption in Calais, it will be 2018 at least before a more permanent solution is in place.9

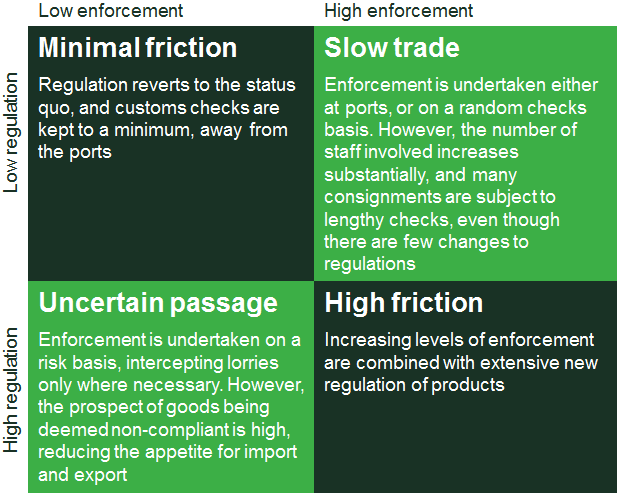

So how might this issue play out? As highlighted in a previous Agenda article,10 scenario analysis is often used to understand the implications of uncertainty, and develop business strategy accordingly. On this occasion, we have considered four scenarios—‘degrees of frictionless’, if you will—all of which assume that some type of Brexit deal will be in place by 29 March 2019.11 These are summarised in Figure 1. For one of these (by no means the worst-case scenario), we have estimated the economic impact relative to the status quo using information from the World Trade Organization (WTO) on the cost of trading across borders.

Figure 1 Four degrees of frictionless

Minimal friction: low regulation, low enforcement

A deal is struck on regulation, such that additional customs checks that are introduced are kept to a minimum, and performed away from the ports.

While some additional costs may be borne by businesses, the economic impact would be broadly negligible, to the extent that this scenario looks similar to the status quo.

Slow trade: low regulation, high enforcement

Enforcement can be undertaken either at the port at the time of movement, or on a random checks basis off-site. However, the number of staff involved increases substantially, and many consignments are subject to lengthy checks.

We estimate that the cost of haulage to businesses of such a scenario would be at least £1bn per year. We assume that the rate of enforcement (i.e. number of vehicles inspected) doubles from 3% of loads to 6%, and that this is applied on both sides of the relevant border. The customs system works such that a lorry driver will know in advance that their load will be checked; however, according to the WTO, checks can take up to two or three hours.

It is worth noting that we consider this to be a conservative estimate—it does not account for the economic costs of the uncertainty involved (it assumes the warning about checks works perfectly, and there is no need for random checks), the extra staff needed (for hauliers, ports and customs officials), the congestion associated with Operation Stack (put at £1bn of short-term cost over four days by the Port of Dover),12 the land required for the additional customs checks, or the wider economic impacts of jobs moving overseas due to uncertainty over the operation of just-in-time logistics. The full cost is likely to be much higher.

Uncertain passage: high regulation, low enforcement

The existing regulations for non-EU imports range from those imposed by the UK Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra)—including those relating to health certificates and import licences—to requirements from the Forestry Commission in relation to the movement of plants.

Enforcement, in this scenario, is risk-based. However, the prospect of goods being deemed non-compliant is high, reducing the appetite for import and export.

The degree of uncertainty—in an industry that relies on goods being delivered ‘just in time’—could lead hauliers to change their business model. Before the Single Market was introduced, many lorries were sent across the sea (to Ireland or France) unaccompanied—i.e. only the trailer was put onto the ferry, and it was picked up by a domestic haulage company at its destination (thereby reducing the cost associated with drivers waiting while customs checks were completed). Arranging for these working patterns to be reversed would require ports to change their facilities, at a cost, while job opportunities for UK-based lorry drivers could decrease.

High friction: high regulation, high enforcement

Extensive regulation of products moving across the border, combined with increased levels of enforcement, will lead to a significant increase in checking conducted at borders.

The Port of Dover has called this scenario ‘Armageddon’,13 as it is concerned that it could potentially lead to an almost-permanent instigation of Operation Stack.

Concluding thoughts

Achieving even a low-friction outcome will not be easy, and businesses in both the UK and the EU need to know very soon the customs rules under which they will be trading. The decision cannot be part of a last-minute deal on the eve of Brexit, due to the time that it will take to get trade moving under the new arrangements. The costs to logistics businesses and their customers, users of the road network and, ultimately, jobs in the UK (and potentially elsewhere in Europe) of a relatively limited increase in friction are likely to be considerable. And ‘no deal’ on a customs union would have extremely serious consequences for the UK and EU economies. Providing a policy direction in this area should be a priority for the UK government.

This article was first published as Meaney, A. (2017), ‘Brexit: the implications for UK ports’.

1 House of Commons Hansard, 1 February 2017.

2 European Commission (2017), ‘Speech by Michel Barnier at the European Economic and Social Committee’, 6 July.

3 Office for National Statistics (2016), ‘UK Balance of Payments, The Pink Book 2016’, 29 July.

4 Kelpie, C. (2017), ‘Majority of exporters travel through Britain to ship goods overseas’, The Independent, 10 March.

5 Personal correspondence.

6 Campbell, P. (2016), ‘UK car industry fears effects of Brexit tariffs on supply chain’, Financial Times, 16 October.

7 Ruddick, G. and Oltermann, P. (2017), ‘A Mini part’s incredible journey shows how Brexit will hit the UK car industry’, The Guardian, 3 March.

8 The Economist (2017), ‘To see how trade may work after Brexit, visit Dover’s docks’, 6 April.

9 Francis, P. (2017), ‘Operation Stack: Court hearing for lorry park plans off M20 put back until October’, KentOnline, 15 May.

10 Oxera (2014), ‘Destination unknown? The future of the aviation industry’, Agenda, December.

11 Alternatively, if it is decided that transitionary arrangements will be in place for some years after 2019, the deal will need to be in place by the end of the transition period.

12 Port of Dover (2015), ‘Open letter from Chief Executive Port of Dover – why the Port of Dover must keep the nation moving’, press release, 6 July.

13 See Jack, S. (2017), ‘Dover delays: Could they become the norm?’, BBC News, 28 March.

Download

Related

Ofgem RIIO-3 Draft Determinations

On 1 July 2025, Ofgem published its Draft Determinations (DDs) for the RIIO-3 price control for the GB electricity transmission (ET), gas distribution (GD) and gas transmission (GT) sectors for the period 2026 to 2031.1 The DDs set out the envisaged regulatory framework, including the baseline cost allowances,… Read More

Time to get real about hydrogen (and the regulatory tools to do so)

It’s ‘time for a reality check’ on the realistic prospects of progress towards the EU’s ambitious hydrogen goals, according to the European Court of Auditors’ (ECA) evaluation of the EU’s renewable hydrogen strategy.1 The same message is echoed in some recent assessments within member states, for example by… Read More