2014: a regulation odyssey

At the end of the last decade, the regulatory regimes for the airports, post, water and energy sectors were put under the microscope, with the aim of assessing how RPI – X regulation was working and how it could be improved. Ofgem’s RPI-X@20, Ofwat’s Future Price Limits, and the Department for Transport’s Review of the Economic Regulation of Airports all hinted at fundamental changes expected in the nature of economic regulation. So what has changed in the intervening years? Did regulation evolve as expected following these reviews? And what does the future hold for regulated companies and their stakeholders?

A lighter touch or heavier hand?

In a number of instances, policymakers and regulatory authorities have looked to replace fixed price caps with ‘lighter-touch’ forms of regulation in an attempt to remove unnecessary intervention in markets.

-

The airports sector has been subject to fundamental change since the last price reviews following the break-up of BAA and the implementation of the 2012 Civil Aviation Act. This Act has enabled the CAA to move away from a one-size-fits-all approach to tailoring the regulatory framework for each airport according to the findings of an airport-specific market power assessment. On the basis of these assessments, the CAA has chosen to deregulate Stansted Airport entirely and to apply a new approach to the regulation of Gatwick Airport based on agreements with airlines (underpinned by a licence). Only Heathrow, which was found to have the strongest market power, continues to be subjected to formal price cap regulation.

-

In 2012, Ofcom’s new regulatory framework for the postal sector involved substantial deregulation of Royal Mail’s retail and wholesale products. Under the new framework, Royal Mail has been granted significantly enhanced commercial freedom for a period of seven years, subject to safeguards to ensure that the company’s return to profitability is driven by an efficiency incentive rather than higher prices. (These safeguards include ongoing monitoring of pricing, profitability and quality of service; a price cap on second class stamps; and extensive regulatory accounting requirements.)

-

The Water Act 2014 has opened up the water retail market to competition for the first time in England and Wales. This will allow non-household customers to switch water and sewerage service supplier.

However, the reduction in regulatory intervention in these markets has not necessarily been mirrored elsewhere. In the (wholesale) water and energy sectors, it is not clear that the regulatory burden has been reduced, despite the intentions of the regulatory reviews. The Future Price Limits and RPI-X@20 reviews both included aims to remove unnecessary complexity and reduce the regulatory burden. As Alastair Buchanan, then CEO of Ofgem, explained on launching RPI-X@20:

A few years ago…I referred to my worries over the increasing complexity of price controls. Arguably the current approach to price controls struggles to meet the call for simplicity from the Better Regulation Commission (as was)…While undoubtedly very clever, some schemes in our price controls, such as the IQI [Information Quality Incentive] sliding scale, are virtually unfathomable to those outside the cognoscenti.[1]

One result of the reviews has been a new focus on ensuring that companies are delivering the higher-level objectives and outcomes that customers and society value, and both Ofwat and Ofgem have described their new approaches to regulation as more targeted, proportionate and ‘risk-based’. In these sectors, companies have been encouraged to take ownership of their business plans, with proportionate scrutiny of these plans, an increased role for customers in the price-setting process, and fast-tracking for the best-performing companies.

However, while there have been substantive changes, the overall complexity and burden of the regulatory frameworks have not noticeably diminished—the menus (IQI in energy and the CAPEX incentive scheme, CIS, in water) live on, the water companies’ June return has gone but new reporting requirements have taken its place, and an ever increasing number of incentive mechanisms have been bolted on to the regulatory package.[2]

In the GB rail sector, meanwhile, the regulatory burden continues to rise. The ORR’s most recent determination (PR13)—promising a ‘balanced package’ and a holistic view of the regulatory settlement—ran to 958 pages, while its ongoing scrutiny of Network Rail’s capital investment becomes increasingly detailed.

Finally, the move towards deregulation in some sectors has been offset by new regulatory roles for the Payment Systems Regulator; the health services regulator, Monitor; the Financial Conduct Authority; and the ORR (which, in its role as ‘the strategic road network monitor’ will scrutinise the Highways Agency’s performance in providing the strategic roads network in England). Deregulation is perhaps narrower than it might at first seem.

Putting the customer at the heart of regulation

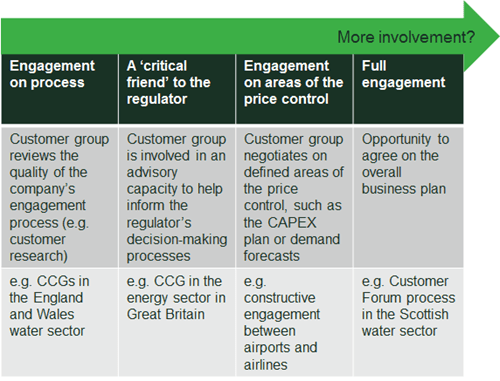

Customer engagement is not new to UK regulation. The CAA’s constructive engagement process—involving early, structured discussion and negotiation between airport operators and the airlines they serve on issues that are central to the price review process—has been a key feature of the airports regulatory regime since 2005. However, such engagement has become more widespread in the latest regulatory cycle, with a number of regulators looking to place customers at the heart of the regulatory settlement.

In the airports sector, the constructive engagement process has continued to play an important role in the determination of prices at Heathrow, while Gatwick’s new commitments-based regulatory regime is based on the notion that commercial negotiations between the airport operator and airlines should deliver better outcomes for users than traditional price cap regulation. The focus on users is reflected in the Civil Aviation Act 2012, which replaced the CAA’s previous statutory duties with a single, primary duty to protect users.

Not surprisingly, the opportunities presented by customer engagement have not been lost on other regulators. In the England and Wales water sector and the GB energy sector, Ofwat and Ofgem respectively have sought to move away from a negotiation between the regulator and companies and towards a need for companies to undertake extensive customer engagement of business plans, as a means of resolving information asymmetries.

-

The regulators have required companies to appoint customer challenge groups (CCGs) responsible for reporting to the regulator on the quality of engagement.

-

Companies have had to put their investment proposals and proposed outcomes to these CCGs, with Ofwat and Ofgem undertaking risk-based reviews of the companies’ resulting business plans.

-

To incentivise customers to put forward well-justified, customer-approved business plans, Ofwat and Ofgem have put in place financial, reputational and procedural incentives for companies that receive ‘enhanced’ status. Such companies have largely been granted the prices and outcomes presented in their business plans.

There is some evidence that these requirements have encouraged companies to reorganise themselves to become more customer-oriented, and both Ofwat and Ofgem are generally of the view that the majority of business plans now are better than they were in previous price review processes. However, despite clear evidence of effective customer engagement in their business plans, Ofwat chose to fast-track just two water companies. Ofgem chose to fast-track both Scottish transmission networks, but only one of six electricity distribution businesses, and no gas distribution networks.

In Scotland, the role of customer engagement has arguably been even more central to the price control process, following the establishment of the Customer Forum in 2011. The main purpose of the Forum is to understand and represent the priorities and preferences of customers and, based on this, to agree a business plan with Scottish Water (or, where this is not possible, to set out why the business plan is not in the customers’ interests).

The customer engagement process appears to have been a success—the Customer Forum and Scottish Water were able to agree on a business plan in January 2014, and the approach has been welcomed by stakeholders in the Scottish water industry. The role of the regulator in the process is notable. The Water Industry Commission for Scotland set out guidance on central price control elements up front, but was subsequently happy to take a back seat, facilitating the engagement and openly stating that it would be minded to accept an agreement between the Customer Forum and Scottish Water, should one be reached.

The CAA is now proposing to take the concept of customer engagement one step further. In October 2014, the CAA’s Group Director of Regulatory Policy, Iain Osborne, announced that the CAA would aim for any new runways for the London area to be financed through commercial agreements between the airport and incumbent airlines rather than through general price controls.[3] It remains to be seen how, or indeed whether, this will play out in practice.

The various models of customer engagement are summarised in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 Models of customer engagement

Source: Oxera.

How do you solve a problem like CAPEX?

Encouraging capital expenditure (CAPEX) was a major aim of privatising utilities in the UK, but regulating CAPEX has long been a challenge for regulators, who have often appeared to be more concerned about companies investing too much than too little. Regulators have traditionally treated CAPEX and operating expenditure (OPEX) separately, with separate efficiency assessments, separate incentive rates and, crucially, separate mechanisms for cost recovery—CAPEX via depreciation of, and a return on, the asset base over time; OPEX on a pay-as-you-go basis. This has raised a number of broad issues, including (but not necessarily limited to):

-

incentives for the company to ‘game’ the regulator by overstating its CAPEX requirement ex ante;

-

a perceived (albeit relatively unproven) bias towards CAPEX over OPEX solutions;

-

weakened potential for comparative efficiency assessments;

-

a high degree of uncertainty over ex ante cost forecasts due to the need to forecast the capital costs of schemes at an early stage of development.

Different regulators have dealt with these issues in contrasting ways. Ofwat and Ofgem attempted to overcome the first one by introducing CAPEX menus, with a view to creating incentives for companies to submit truthful CAPEX forecasts, thereby reducing the scope for gaming, while maintaining within-period efficiency incentives. Despite the complexity of these approaches, they continue to form an important part of the regulatory regimes in the England and Wales water and GB energy sectors.

Ofwat’s PR14 review and Ofgem’s RIIO framework have, however, led to a further significant change with the adoption of a total expenditure (TOTEX) approach to cost assessment and recovery. Under this approach, a predefined percentage of TOTEX (‘slow money’) is added to the regulatory asset base (RAB), while the remainder (‘fast money’) is recovered on a pay-as-you-go basis. The capitalisation percentage (i.e. the proportion of ‘slow money’) is determined up front and is unaffected by outturn CAPEX. The intention of the approach is to remove CAPEX bias, equalise outperformance incentives across cost types, and facilitate a single efficiency assessment.

The CAA and ORR have followed a different approach. For Network Rail and Heathrow, OPEX and CAPEX have continued to be assessed and recovered separately, and there has been little appetite to introduce a menu (perhaps due to the limited potential for comparative assessment in these sectors). Instead, the CAA and ORR have preferred to use alternative mechanisms such as CAPEX triggers and detailed bottom-up efficiency assessments. However, the issue of setting a reasonable and robust cost allowance for projects at an early stage of development has continued to create problems. The regulators’ response has been a new ‘split CAPEX’ approach.

Under this approach, CAPEX is split into two buckets: ‘core’ and ‘development’. ‘Core’ CAPEX covers projects that are sufficiently advanced to be costed with reasonable confidence ex ante, and is included in the baseline price cap. An indicative allowance for development projects (that are not sufficiently advanced to be agreed at the time of the price review) is also included in the baseline price cap, but the cost allowances for individual development projects will subsequently be determined within period. (In Network Rail’s case this applies only to early-stage enhancements and civils.) The total CAPEX allowance captured in the price cap formulation will then be revised within period, such that the companies will not be remunerated for projects that are not undertaken.

The impact of this new approach is as yet unclear but, on paper at least, it represents a further blurring of the line between ex ante and rate of return regulation, with an increased focus on remunerating investment costs ex post. The result could be savings to customers by reducing overestimation of future costs or diluted efficiency incentives combined with a higher regulatory burden.

Overall, there is still no magic bullet to overcome the issues surrounding the regulation of capital investment.

Diminishing returns?

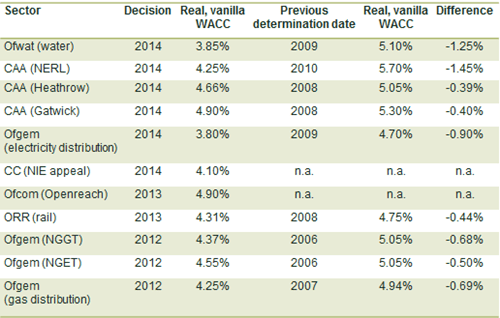

As ever, the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) allowed by regulators is both a central component of the charges formula and a key indicator to investors of the returns they can expect to earn over the price control period.

-

The going rate for the real, vanilla WACC is now firmly below 5% in the UK.[4] A combination of capital market developments and a focus on ensuring efficient financing costs has led regulators to make significant reductions to the WACC relative to previous settlements. Ofwat followed through on its promise that water companies’ WACCs would ‘start with a 3’ (ultimately 3.85%, down from 5.1% at PR09);[5] the CAA cut around 40 basis points (bp) from the airports’ (vanilla) allowances; and Ofgem’s determinations have incorporated real, vanilla WACCs ranging from 3.8% (RIIO-ED1) to 4.8% (for the two fast-tracked companies at RIIO-T1).[6]

-

Companies and regulators do not see eye to eye on the WACC. While disagreement on the WACC is nothing new to regulation, the level of disagreement continues to be significant. For example, Ofwat’s (real, vanilla) WACC allowance of 3.85% was 45bp below the average figure proposed by water companies. In the airports sector, the difference was even more pronounced. Heathrow’s initial bid (RPI + 5.9%) incorporated a real, pre-tax WACC of 7.1%—nearly 1% above its previous settlement. The CAA eventually settled on a real, pre-tax WACC of 5.35% (a full 175bp below the initial ask), with Heathrow’s proposal to unilaterally cut its CAPEX seemingly falling on deaf ears.

-

What the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) says matters. The WACC allowances for GB companies have, somewhat unexpectedly, been heavily influenced by circumstances in Northern Ireland. In 2012, NIE appealed its price determination to the UK CC (now the CMA). The outcome of the redetermination was, among other things, a 45bp reduction in the WACC (on a real, vanilla basis) relative to that allowed by the Utility Regulator. The ramifications of the CC’s decision were felt widely (see Table 1 below). The CAA, already providing a sizeable reduction to the allowed WACC for Heathrow and Gatwick, further reduced its total market return assumption to be consistent with the CC’s analysis.

Table 1 Real, vanilla WACCs across sectors

Note: NERL, NATS (En Route) Ltd. NGGT, National Grid Gas Transmission. NGET, National Grid Electricity Transmission.

Source: Various regulatory determinations; Civil Aviation Authority (2014), ‘Estimating the cost of capital: technical appendix for the economic regulation of Heathrow and Gatwick from April 2014: Notices granting the licences’, CAP 1155, February, p. 47, Figure 7.3.

A political game

There are widely considered to be clear benefits to having regulatory bodies that are independent of central government. In particular, independence is usually believed to create enhanced stability and to facilitate longer-term decision-making with reduced government intervention. This has the impact of enhancing investor confidence in the regulated sectors, which has led to key investment benefits. Indeed, industry participants and credit rating agencies have argued that policies that threaten the independence of regulators—such as price freezes imposed by government—can have a negative impact on future investment in the sector.[7]

Regulators generally seem to be facing an increasing number of trade-offs as more (conflicting) regulatory duties are introduced.[8] At the time of privatisation, regulators had a relatively simple brief: to promote competition and to prevent monopoly pricing where competition was not feasible. The division of responsibility between government and regulators was therefore relatively clear-cut. Over time, additional duties have been introduced—covering, for example, environmental and social objectives—and have created more scope for potential conflicts when regulators are taking decisions.

Moreover, there has recently been some evidence of an increase in direct government intervention. In the UK energy sector, for example:

-

the key driver of regulatory reform has been integrating the carbon agenda into regulatory activity;

-

equally, the drive for energy tariff simplification has been led by the current government;

-

Ed Miliband, Leader of the Opposition, announced in 2013 that the Labour Party plans to freeze energy prices for 20 months should it win the next election.[9]

Furthermore, there is a clear trend towards supranational regulation in Europe. All companies, and regulators, need to be compliant with an increasing volume of EU-wide legislation and regulations and, in a number of sectors (most notably air traffic control), the European Commission is taking on explicit regulatory powers.

These initiatives could contribute to a blurring of the division between the roles of government and regulator. Regulators would benefit from clearer and more transparent guidance from government on what each sector is expected to deliver and how any conflicting objectives should be traded off, as well as clarity on which party is expected to do what.

The state of regulation

As regulation has evolved in the UK, the simplicity of the original RPI – X model has been replaced by an increasingly complex set of incentives, assessment tools and regulatory requirements. Even as markets have been opened up to competition, or as lighter-touch regulatory regimes have been introduced, regulators have found themselves setting detailed market rules and reporting requirements. The negotiated settlement in the Scottish water sector has been heralded as a success by all parties involved, and perhaps presents a view into the future of regulation—a future in which educated customers play a central role in the price-setting process, with the role of the regulator being to set the wider parameters and facilitate constructive discussion between companies and their customers. For now, though, regulation remains (for the most part) as complex as ever.

Contact: Dr Leonardo Mautino

[1] Buchanan, A. (2008), ‘Ofgem’s “RPI at 20” project’, speech at SBGI, 6 March, pp. 5–6.

[2] The June return was a detailed annual data submission provided by each company in the England and Wales water sector to the regulator, Ofwat. The regulator stopped collecting the June return from 2011/12 onwards.

[3] Osborne, I. (2014), ‘Economic regulation of new runway capacity’, Beesley Lecture, 23 October.

[4] The vanilla WACC is the weighted average of the post-tax cost of equity and the pre-tax cost of debt, and therefore abstracts from all considerations of tax.

[5] Brown, S. (2013), ‘Water 2013: Keynote opening address’, November, p. 3.

[6] These values will change over time due to debt indexation.

[7] Dunkley, J. (2013), ‘Big Six energy firms face investor exodus over political interference in pricing’, The Independent, 17 November.

[8] Ross, C. (2013), ‘Independent economic regulation: a tale of two paradoxes’, Agenda, November.

[9] New Statesman (2013), ‘Ed Miliband’s speech to the Labour conference: full text’, 24 September.

Download

Related

Ofgem’s RIIO-3 Sector Specific Methodology Decision

On 18 July 2024, Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Decision (SSMD) for the forthcoming RIIO-3 price control period for electricity transmission (ET), gas transmission (GT) and gas distribution (GD) networks.1 This follows Ofgem’s consultation on the matter in December 2023.2 RIIO-3 will last for… Read More

The future funding of the England & Wales water sector: Ofwat’s draft determinations

On Thursday 11 July, Ofwat (the England and Wales water regulator) published its much anticipated Draft Determinations (DDs). As part of the PR24 price review, this sets out its provisional assessment of allowed revenues and performance targets for AMP8 (2025–30)—and will be of great interest to water companies, investors,… Read More