Speech given by Jonathan Haynes, Senior Consultant, Oxera Consulting LLP

At FESE Convention, Dublin

5 June 2019

Download the speech.

Download the slides.

I’m delighted to be here today at the FESE Convention – my first, but I believe it is your 22nd. There has been a lot of change affecting exchanges

and the markets in which they operate over those 22 years.

We (at Oxera) have been working with FESE and its members over the past few months to study how the functioning of equity markets in Europe has changed over that time, focusing on the role of price formation and market data.

As many of you will know, there is an ongoing debate about the provision by stock exchanges of market data services. This debate often overlooks the links between market data services, trading and price formation, and the design of the equity trading market more generally.

The objective of our analysis has been to inform the policy debate on the design of equity trading in Europe. In particular, we looked at three aspects:

- price formation;

- the impact of MiFID on the design of the market; and

- the links between price formation and market data services.

In this presentation I will touch on the key messages from our study. But if you are hungry for more of the underlying analysis, the full report of over a hundred pages is published on the FESE website.

Price formation

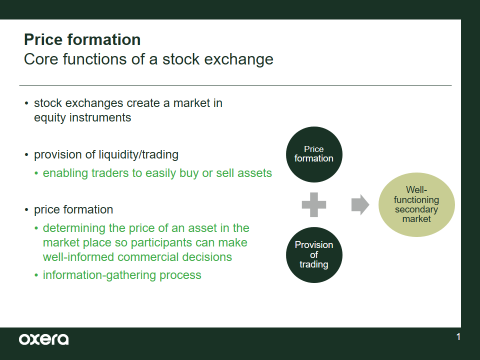

First, let me begin with price formation. [Slide 1]

We heard this morning about the role of exchanges in capital markets.

Stock exchanges undertake a range of activities and fulfil a number of functions. When defining stock exchanges, their role is typically captured in terms of their listing services and trading function (or liquidity provision). An important related function is that of price formation.

While vitally important, price formation is often not mentioned explicitly—partly perhaps because it is much less tangible, and partly because it is (sometimes) assumed to be part of the trading function. Indeed, trading and price formation are closely related—but more on this later.

So what do we mean by price formation?

In our report we turned to the well-established economics literature on market microstructure to understand the price formation process and its benefits to the economy.

Price formation is an information-gathering process which ensures that market participants know enough about the prices of the assets being traded in the market, so that they can make well-informed decisions.

Like other markets, stock markets bring together buyers and sellers and establish prices which ensure that demand equates available supply.

Yet, distinct from other markets, the underlying ‘goods’ being traded here are not consumed soon after purchase (as in a market for apples, or oranges) or over a period of time (as in a market for antiques, or houses).

With financial securities, the ‘goods’ are prospects on earnings in the distant future that are hard to predict with confidence. When you buy a financial asset, you are implicitly making assumptions about the future stream of cash flows from that asset. These cash flows are uncertain, hard to predict, and the person you are buying from may know more about the state of those cash flows than you.

This unique characteristic makes the information-gathering process extra important in financial markets.

This price formation process is a central ingredient to well-functioning markets. In fact, it could be argued that the whole point of financial markets is to incorporate information. For example, the job (the ‘social purpose’) of a stock trader is to try to find out new information and incorporate it into stock prices.

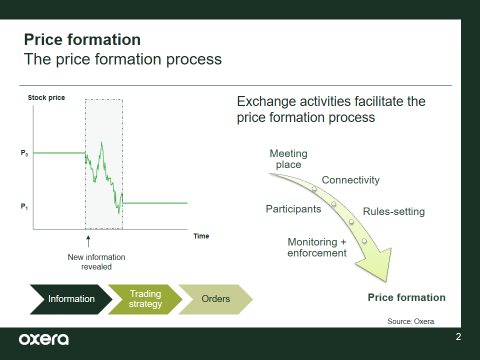

In the case of equity markets, the price formation process is usually facilitated by a trading venue, with various parties contributing in different ways. [Slide 2]

Trading venues compete on the quality of price formation via their activities. A venue will be successful in trading only if its price formation process is reliable and of high quality.

This is about setting fair and consistent rules. It is about attracting the right mix of investors to trade. It is about ensuring connectivity, in the good times and the bad.

Historically, this may have been about attracting interested investors to a physical building. Nowadays, it is more about investing in capacity and maintenance of matching engines, and proactively responding to new threats, from cyber-attacks, fraud, and operational risks, for example. Exchanges need to continually update and improve their systems to remain commercially competitive.

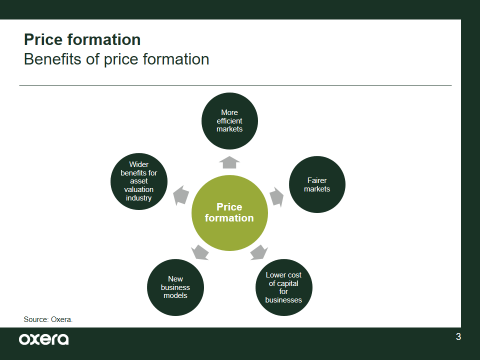

What are the benefits to price formation? [Slide 3]

The ultimate beneficiaries of an effective price formation process are the investors, businesses, fund managers, regulators and market authorities that take decisions based on those prices.

Accurate prices from stock exchanges lead to a number of benefits.

- More efficient markets—better price formation leads to less frequent costly price shocks.

- Fairer markets—fairness in markets requires a reliable price formation process with effective detection and deterrence. Confidence in prices then leads to the use of those prices.

- Lower cost of capital for European businesses—if information is quickly incorporated into asset prices, there will be less asset volatility and a lower cost of capital for firms.

- Wider benefits for the asset valuation industry. For example, the broader valuation industry uses the accurate prices formed on stock exchanges to determine the value of other assets.

And last, but by no means least…

- Improved products and new business models—the price formation provided by exchanges has led to new products and business models, including dark pools. This has resulted in more choice and competition for trading and new propositions to customers.

MiFID and market design of equity trading

The second theme in our report was to look at the impact of regulatory change on the market design of equity trading and price formation.

Over the past decade we have witnessed a fundamental change in how equity trading operates in Europe. This has been driven by technological development and entry by new players—supported by regulatory change.

Before 2007, trading on a given stock took place on only one (or possibly two) trading venue(s). The stock would typically trade on the same venue on which it was listed. As such, there was a direct link between the primary and secondary markets.

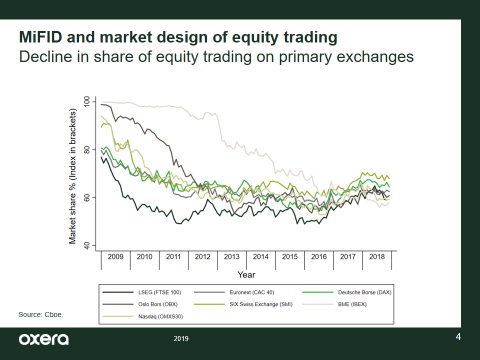

This changed in 2007, with the introduction of the European Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID I). MiFID I opened up competition for equity trading, delivering more choice and lower trading costs for European businesses.

The ten years that followed were associated with:

- a decline in the share of equity trading on primary exchanges; [Slide 4]

- significant growth in algorithm and high-frequency trading strategies;

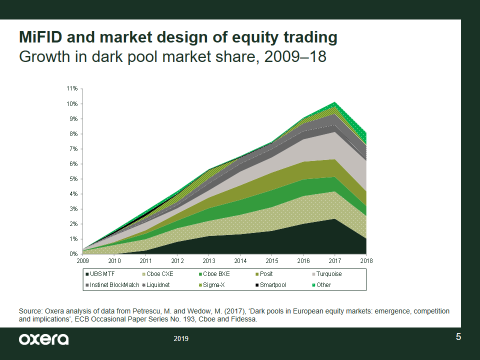

- a steep rise in dark trading—i.e. trading on dark venues and over the counter (OTC), without pre-trade transparency. [Slide 5]

Since 2018, the implementation of MiFID II (the successor legislation of MiFID I) has continued the trend of promoting competition for equity trading, with a focus on improving transparency and price formation in financial markets.

New rules were put in place to limit the amount of dark trading, and to promote trading on the more transparent exchanges, which lie at the heart of the price formation process in equity markets.

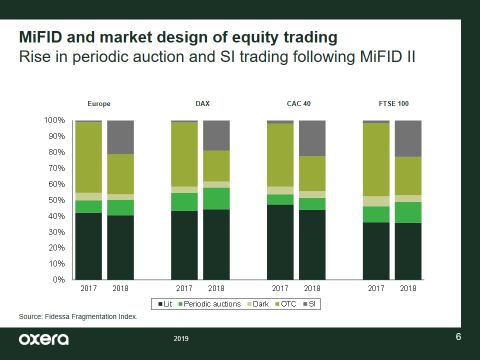

If we look more closely at the recent trends, since MiFID II has been in place, we see [Slide 6]:

- a small reduction in the volume of trading on dark pools;

- an increase in trading on systematic internalisers, displacing some of the OTC trading that previously occurred on broker-crossing networks;

- a shift towards greater use of periodic auctions, although this remains a very small share of the overall market; and

- a small drop in lit trading—which is perhaps surprising given that one of the objectives of MiFID II was to promote transparent trading. The proportion of equity trading taking place on lit exchanges in Europe has fallen to below 40%.

More choice for users is generally a positive market development. [Slide 7] For example, the opportunity for investors to use dark trading to protect themselves from market impact is beneficial from an economics perspective. Likewise, periodic auctions can protect investors from being front-run by high-frequency traders.

But going forwards, we also need to make sure we preserve the quality of price formation on equity markets. And we don’t want that to be undermined.

At the end of the day it is the quality of the price formation that is facilitating this greater choice.

Market data

So what does this all have to do with the debate about the costs of market data?

Well, market data provided by stock exchanges is the outcome of a dynamic price formation process.

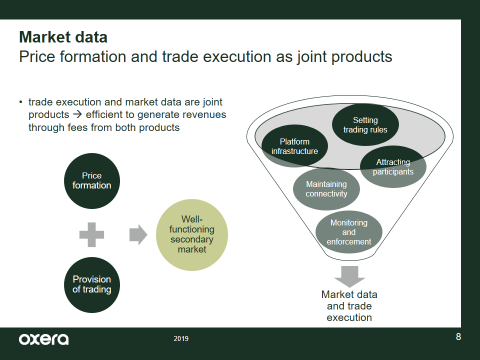

For stock exchanges, trade execution and market data are joint products[1] with joint costs, meaning that it is not possible to generate one without the other. [Slide 8]

The market data points we are referring to in this debate are the direct outcome of the price formation process and the trading activities on the limit order books of stock exchanges.

In the case of joint products, the economics literature suggests that it is efficient to generate revenues through fees from both products. Indeed, this is what stock exchanges do in practice. They charge their users trade execution fees and market data fees.

There has been a lot of discussion about the costs of market data to fund managers and brokers. But, from a public policy perspective, the key question is really: ‘What is the impact of the current costs of market data on end-users?’

Before answering this question, let me provide a bit more background on market data.

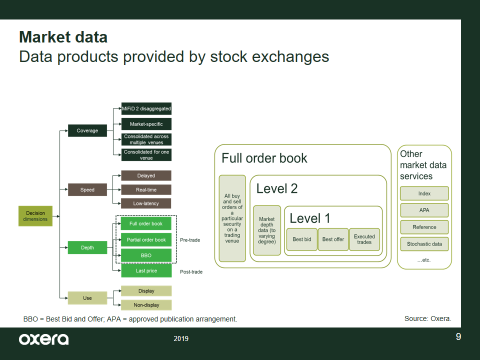

Data products from exchanges vary according to coverage, speed, depth and use. The most well-known packages are the so-called ‘Level 1’, ‘Level 2’ and ‘full order book’ packages, which provide varying levels of detail on the orders submitted to the book. [Slide 9]

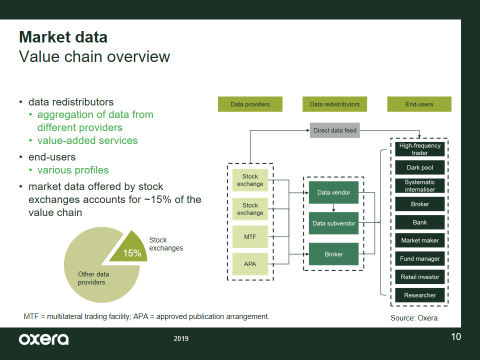

The value chain for market data is long and growing. [Slide 10] Trading venues provide market data to a variety of users. Data vendors or brokers may redistribute or consolidate this information. Other firms may offer value-added services, such as analytics or more advanced connectivity services. Then, there is a wide mix of end-users, including brokers, fund managers, and other venues (that may commercially decide not to invest in price formation themselves).

During the preparations of MiFID II, questions were raised about the cost of market data to users.

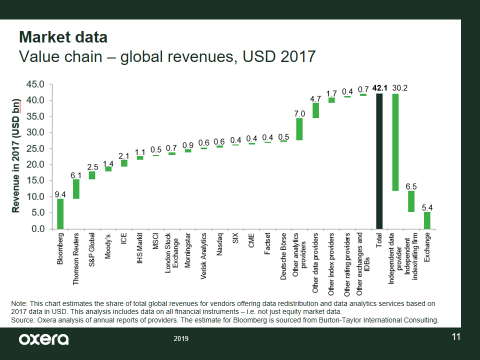

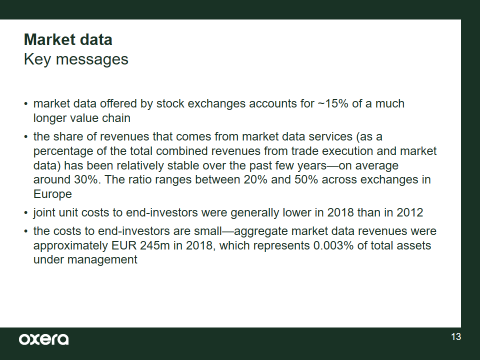

If we look at the revenues from the market data industry, our estimates suggest that 15% of the value chain is data provided by the stock exchanges. [Slide 11]

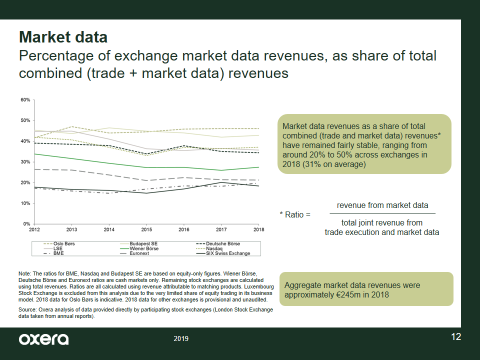

To investigate further, we collected data from the FESE members and looked at a range of metrics [Slide 12] – only a few of these are shown in the slide.

We have looked at this from the end-investor perspective. Given the joint product nature of trade execution and market data, this means analysing not just trade execution costs, but also market data costs.

Based on the data collected, we have observed that:

- total market data revenues have been fairly stable over time;

- most revenues associated with the joint product of trade execution and market data still come from trade execution. On average only 30% of the revenues (as a percentage of the total combined joint product revenues from trade execution and market data) come from market data;

- this share of revenues from market data has remained fairly stable over time;

- the costs are small—aggregate market data revenues were approximately EUR 245 million in 2018, which represents 0.003% of total assets under management (a proxy for the value to end-users of the investment made with the data). [Slide 13]

A key question is what has happened to the total costs of trading (i.e. trade execution and market data) to end-investors over the past few years. We see that the unit costs of trading—measured as combined revenues as a proportion of the value of trading—have actually declined in recent years.

It is interesting that data consumption has gone up while revenues from stock exchanges have remained fairly stable.

If data is becoming more expensive, we need to understand why. Based on our analysis, it does not appear to be the equity market data provided by stock exchanges that is driving such a trend.

Looking ahead

One year on from the introduction of MiFID II, and the objectives of the EU’s Capital Markets Union agenda are as important as ever. The European Commission and the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) are therefore closely reviewing the outcomes of these regulatory interventions. ESMA is currently reviewing measures put in place to preserve price formation, including the effectiveness of the caps on dark trading. It recently proposed changes to level the playing field for on- and off-exchange trading in terms of minimum tick sizes.

This is progress. However, some interesting policy questions remain to be analysed in the months and years ahead:

- What will be the impact of greater competition for equity trading on the development of price formation going forward?

- How have the overall costs of the full value chain of market data for end-users changed over time? And how do these costs compare to the value that the data generated has provided to those users?

- Are any users being deterred from trading in equity markets due to the changing market structure? Have the equity markets in Europe become more or less efficient?

- What else can be done to ensure the broader development of transparent equity trading markets in Europe?

These are all important questions. And I would encourage you to think about them from an end-investor perspective. Let us not forget that these are the ultimate users of these markets. Thank you.

Slide 1

Slide 2

Slide 3

Slide 4

Slide 5

Slide 6

Slide 7

Slide 8

Slide 9

Slide 10

Slide 11

Slide 12

Slide 13

[1] A joint product is an economic concept to explain a situation in which the production of one product simultaneously involves the production of one or more other products.