Fragmentation, competition and the EU CSD landscape

There is growing attention from policymakers on the design and functioning of the market for central securities depository (CSD) services in the EU.1

This is an important debate with implications for investment and the real economy. The efficiency of trading and post-trading services affects overall execution costs for investors in the EU and, ultimately, the cost of capital for EU companies.

To date, much of the debate surrounding post-trade market structure in the EU has focused on ‘fragmentation’—a frequently used term that can lead to confusion. Drawing on a recently published Oxera report, in this article we provide some important insights into the design and functioning of the market for CSD services.2

Why do we care about fragmentation?

Fragmentation is sometimes used by market participants and policymakers as a shorthand for a market structure in which there are ‘too many’ providers. From an economics perspective, a potential problem of having too many CSDs in the EU is that individual infrastructure providers are too small. In markets where fixed costs are important, larger firms benefit from economies of scale: fixed costs can be spread across a larger volume of transactions, leading to lower unit costs. Fragmentation can mean that individual providers are too small to benefit from economies of scale, resulting in high unit costs.

Moreover, the very large number of CSDs in the EU also means that custodians have to establish and maintain a lot of connections to individual CSDs potentially resulting in further additional costs in the value chain.

Addressing insufficient supply-side economies

Some policy discussions, including the 2024 Draghi report on European competitiveness, have raised the idea of establishing a single EU-wide CSD to address insufficient supply-side economies.3 Indeed, this is similar to the model that exists in the USA, where the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC) is the single CSD for US equities and corporate bonds. Would this model work for the EU today?

First, economies of scale do not automatically mean that the optimal market structure consists of a single provider. Indeed, many sectors are characterised by significant economies of scale but can still support multiple (large) providers. For example, although mobile phone networks come with high fixed costs, the market can still sustain several different players. There are typically a limited number of mobile networks in each country, ensuring each network can be sufficiently large to benefit from economies of scale.

Second, in modern economies, partly as a result of technological developments, it has become relatively rare that economies of scale are so substantial that the market can only sustain one provider. The main exceptions are some of the utility sectors with regulated monopolies.

Third, it is worth noting that the US post-trade market structure was not created by regulation, but emerged from a wave of market-driven consolidation in the 1990s, as DTCC merged with several other US CSDs. 4 At the time this consolidation took place, interoperability arrangements, such as those later facilitated by the TARGET2-Securities (T2S) platform in the EU, did not exist.5 This is not the case in the EU today, where T2S provides a form of interoperability.

Finally, importantly, from an economics perspective, full structural consolidation in a market is not a necessary condition for achieving scale efficiencies. These outcomes could be achieved by allowing competition to drive efficiency, so long as the market structure supports these dynamics. Generally speaking, effective competition forces companies to become more efficient over time and reach an efficient level of scale. This means that where there is scope for further economies of scale and where effective competition is feasible, economies of scale can be achieved (and fragmentation can be reduced) by facilitating CSDs to compete.

Moreover, establishing a single EU-wide CSD (and therefore eliminating the potential for competition between CSDs) would come with various disadvantages, particularly in markets where service innovation is a relevant factor in delivering good outcomes for end-users. Here, dynamic competition can drive incumbent firms to continually invest in improved services, or can mean that investment in new technologies is best undertaken by a new entrant (so-called ‘creative destruction’).

Would competition create more fragmentation?

While competition can resolve the current problem of fragmentation due to insufficient supply-side economies, is there a risk that competition for CSD services would create an additional form of fragmentation?

Competition would indeed mean potentially having more than one CSD active in a particular country (e.g. providing central settlement in the same stock). This is a different type of fragmentation altogether and is a question of ‘network effects’ (not economies of scale).6

In services that bring together users, fragmentation may result in insufficient network effects. This has been the primary concern at the trading-platform level. The objective of introducing competition for trading was to impose competitive pressure on the incumbent exchanges. However, although the introduction of competition was welcomed, there was a concern that trading fragmentation (i.e. a stock being traded on multiple platforms) could potentially result in liquidity fragmentation (i.e. a reduction in network effects), which would be to the detriment of end-users.7 Do the same concerns about sub-optimal demand-side economies arise in CSD services? There are features of the CSD landscape in the EU that mean this is not the case.

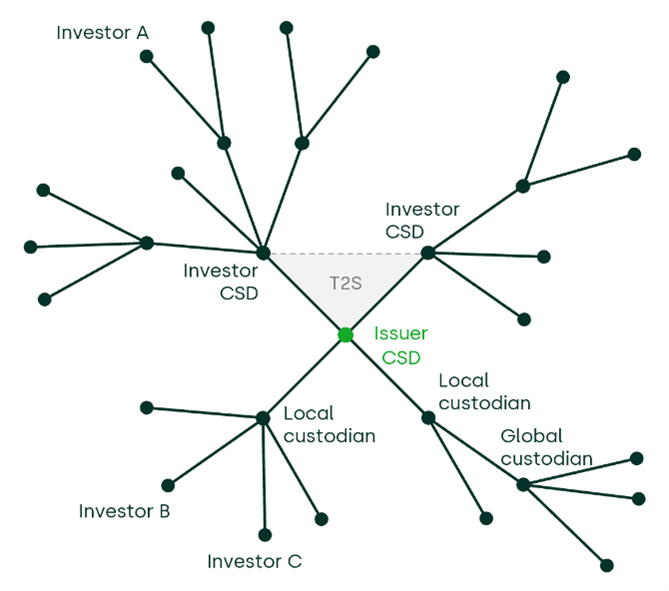

First, each individual security is currently issued into a single issuer CSD, which is responsible for establishing and maintaining the primary book-entry register for that security. The fact that different securities are issued and settled through different CSDs does not fragment the settlement and custody of these individual securities, because all trades ultimately converge on the same point of final settlement and custody. In other words, whereas trading stock A on different trading platforms may result in fragmentation (of liquidity), a trade in stock A is always ultimately settled through the same central settlement venue or further up the chain of custody, if both parties happen to use the same intermediary.8

Second, T2S provides a common platform for central settlement for participating CSDs. By enabling settlement to take place between CSDs, T2S effectively allows for a form of ‘interoperability’. As long as all CSDs in the EU are connected to and use the T2S platform, all CSDs together form a single network. In other words, if a security is settled using two different CSDs, this does not result in fragmentation given the availability of T2S.

This structure is depicted in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 Stylised example of a post-trade network

Source: Oxera.

Together, these features mean that for the settlement of a transaction in a particular security, the seller and buyer can always find each other even if they use different custodians and/or different CSDs. In other words, having multiple CSDs does not in itself fragment the network and does not result in suboptimal network effects.

The future landscape

EU initiatives such as T2S have already laid the foundations for competition, although effective competition has not yet materialised in practice. However, this is likely to change, for example as a result of Euronext’s various CSD initiatives.9

Taking Figure 1 above as a starting point, we can consider how competition could look at different parts of the value chain.

If one takes an end-investor perspective, there are already multiple routes of accessing central settlement systems and the relevant issuer CSDs. Global custodians already compete with each other to provide access in the most efficient way possible, so end-investors benefit from their economies of scale.

What about central settlement? As noted above, the common platform provided by T2S, together with CSD links, enables investors to settle (and hold) shares issued in other CSDs. This separation of central settlement from the role of the issuer CSD means that it is possible for investors to have a choice over central settlement provider in a given security—i.e. T2S provides the foundation for head-to-head competition.10 Moreover, the degree to which central settlement providers can offer scale efficiencies to investors is likely to play an important role in future competition.

What about issuance? The economic characteristics of issuer CSDs mean that, historically, there has been limited competition at this level of the value chain. While companies have a choice to list at different exchanges in the EU, the decision of where to list is influenced by a range of factors (beyond CSD services), and once an exchange has been chosen, to date, there has been virtually no choice of issuer CSD.

Euronext has presented its strategy to compete directly with existing issuer CSDs. This means that listed companies in several member states will have a choice of provider for issuance. Given the economic characteristics of issuer CSDs, this competition is likely to have two important flavours:

- competition will be ‘for the market’, i.e. Euronext will compete to be the single issuer CSD for a given listed company (i.e. there is no ‘multi-homing’);

- issuer CSDs will compete to attract issuers based on service proposition and the overall reduction in execution costs (i.e. custody, settlement and asset-servicing fees) they offer investors through scale economies, which ultimately feed through to issuers’ cost of capital. Indeed, the link between lower execution costs and lower costs of capital is well established in the economics literature.11

Conclusion

To summarise, policymakers have created the sufficient conditions for competition in CSD services to work and it is now time to fully embrace this. Indeed, Euronext’s CSD strategy takes advantage of the common platform structure provided by T2S to improve user choice and introduce competition. Now that the regulatory framework and infrastructure is in place, what is needed is to ensure more CSDs are connected to T2S and the corresponding CSD links are set up. Competition, supported by the adoption of T2S by all EU CSDs, is the mechanism through which the current fragmentation and inefficiency can be addressed.

Footnotes

1 A CSD services typically comprise: 1) securities issuance i.e. the process of establishing a security in book-entry form; 2) settlement i.e. the completion of a transaction through the transfer of ownership and monies; 3) custody i.e. the safekeeping and administration of securities held in the CSD; and 4) asset servicing e.g. the processing of corporate actions, dividends and voting.

2 Oxera (2025), ‘The design and functioning of post-trading markets in the EU’, October, https://www.oxera.com/insights/reports/the-design-and-functioning-of-csd-services-in-the-eu/. This report was commissioned by Euronext.

3 See Draghi, M. (2024), ‘The future of European competitiveness: Part B – in-depth analysis and policy recommendations’, a report by Mario Draghi, September, European Commission.

4 For more discussion of the history of DTCC, see: Rodengen, J.L. (2023), ‘The story of the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation’, DTCC.

5 T2S is a common securities settlement platform owned and operated by the Eurosystem. It was launched in 2015 and facilitates Delivery-versus-Payment (DvP) settlement using central bank money for the cash leg of the settlement.

6 Networks effects arise when the value of participating in a given infrastructure is a function of the level of participation by others in the market. Network effects, as demand-side economies, can be one-sided (i.e. between the same type of user) or two-sided (i.e. between different types of user, such as issuers and investors).

7 Trading fragmentation (i.e. a stock being traded on multiple platforms) does not necessarily result in liquidity fragmentation. For an explanation and analysis, see our separate Agenda article: Oxera (2020), ‘Has market fragmentation caused a deterioration in liquidity?’, Agenda, December,

https://www.oxera.com/insights/agenda/articles/has-market-fragmentation-caused-a-deterioration-in-liquidity/. Other relevant work includes: Oxera (2019), ‘The design of equity trading markets in Europe’, report prepared for the Federation of European Securities Exchanges’, March, https://www.oxera.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/design-of-equity-trading-markets-1-1.pdf; Oxera (2020), ‘Primary and secondary equity markets in the EU’, report prepared for the European Commission DG FISMA, November, https://www.oxera.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Oxera-study-Primary-and-Secondary-Markets-in-the-EU-Final-Report-EN-1.pdf; Oxera (2021), ‘The landscape for European equity trading and liquidity’, report prepared for the Association for Financial Markets in Europe, May, https://www.oxera.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/European-equity-liquidity-landscape-Q1-2021-Final-26-05-2021.pdf.

8 This is referred to as settlement internalisation.

9 Euronext (2024), ‘Strategic plan: Innovate for Growth 2027’, November, https://www.euronext.com/en/innovate-for-growth-2027.

10 Euronext has announced that it will designate Euronext Securities as the default CSD for the settlement of equity trades on Euronext Amsterdam, Paris and Brussels (where settlement currently takes place on Euroclear CSDs), with market participants having the option to make their own choice about which CSD to use for settlement. This model is only possible due to the common platform structure of T2S and the existing network links that Euronext has established with other EU CSDs.

11 See Domowitz, I. and Steil, B. (2001), ‘Innovation in Equity Trading Systems: the Impact on Transactions Costs and Cost of Capital’, in R. Nelson, D. Victor and B. Steil (eds), Technological Innovation and Economic Performance, Princeton University Press. The authors show that higher (lower) transaction costs for investors are associated with lower (higher) asset prices. Investors who pay higher (lower) fees to acquire or dispose of a security require a higher (lower) return from holding it, and thus bid the price down (up); this ultimately increases (decreases) the cost of capital for listed companies.

Related

Decoding the Digital Networks Act: the future of the EU electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework

On 21 January 2026 the European Commission published the long-awaited draft of its Digital Networks Act (DNA)—the proposed new regulation that seeks to ‘modernise, simplify and harmonise EU rules on connectivity networks’.1 As the draft is now being reviewed by the European Parliament and the Council, representing the… Read More

Oxera AI Policy Map – January 2026

For this third edition of the AI Policy Map,1 we have updated our database that tracks key national and supranational AI policy developments across the European Economic Area (EEA) and the UK. This curated collection brings together legal texts, strategy documents and other influential publications relevant to the… Read More